Djamu, the Australian Museum's gallery of Aboriginal art, has what can best be described as an ambiguous relationship to its parent museum. The Australian Museum is the country's oldest and in its history and collection are traced histories of the ways Europeans saw indigenous cultures.

Storage holds records of artifacts collected as evidence of the habits of a 'primitive' race, seen almost as another species, less than human. I have a childhood memory of displays of skeletons under glass, shown with exotic aged objects. But that was many years ago, and the Australian Museum has become a pioneer in the practice of removing sacred histories from public display while creating keeping places for traditional owners. In recent years the Museum has embraced a broad interpretation of its anthropological brief, looking at issues which concern living Aboriginal people. Some exhibitions in the parent institution have embraced Aboriginal achievements in arts and crafts, while others have taken good intentions to issues of social justice - imprisonment, and displacement.

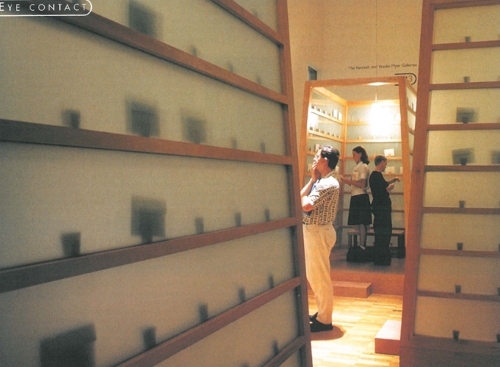

Djamu, conveniently located over a kilometre away from the Museum, down at the old Sydney Customs House, was always going to be more confrontational. Indigenous concerns are not academic here, they are everyday reality. The curator, John Kirkman, is not Aboriginal, but his staff are either Aboriginal or work closely within the Aboriginal community. As such they are aware that the issues facing indigenous Australians are also facing the indigenous peoples of New Zealand, the Americas, Japan, and India. Because of its status as part of an anthropological museum Djamu is less entranced by the seductive images of Western Desert painting, and more interested in the energy of the work of young artists, especially when they are from within their culture.

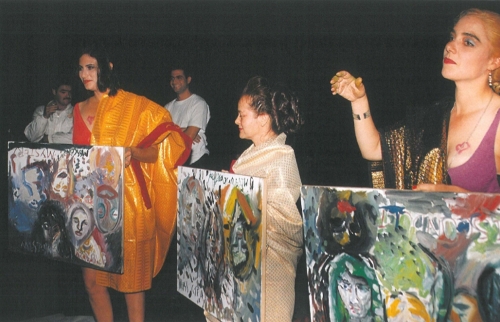

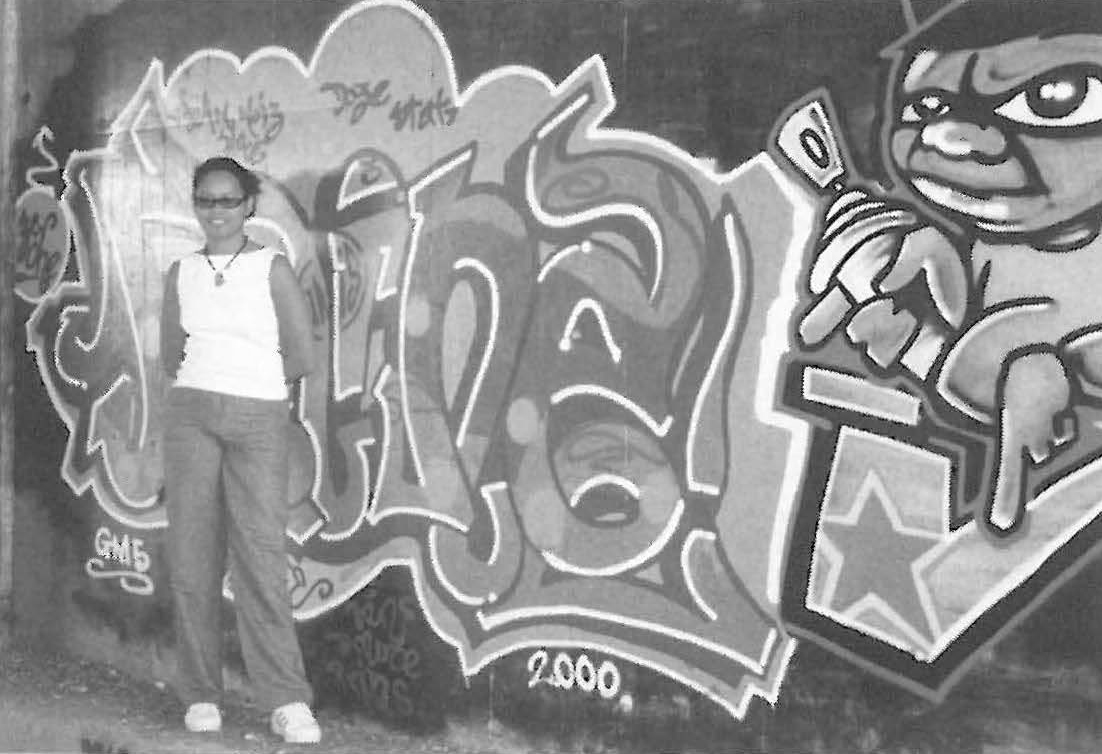

Out of these two ideas, the raw immediacy of graffiti and the concerns of another indigenous culture, comes Back to the Walls, an exhibition of murals from two cultures in transition.

The second culture is that of the tribal women of the Hazaribagh region of Bihar, in India. In the terminology of the dominant Hindus these people are 'scheduled castes', untouchables. They are the aboriginal people of the region, the first inhabitants of the subcontinent, displaced by the conquerors of the north. As such, and because of their continuing struggle for recognition there is considerable sympathy between these people and Australian Aborigines.

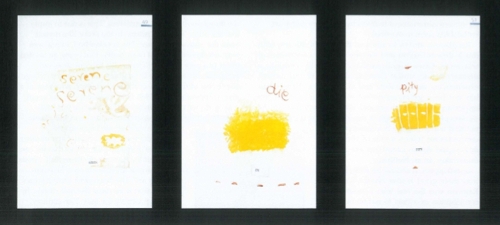

Then there is art. For many years the tourist shops of New Delhi have featured delicate watercolour paintings of peacocks and mandalas, paintings in cerise vegetable dye and black pigment. The tourists are told these are from the peasant women of Bihar, and so they are. But the produce for market is but an echo of the real work.

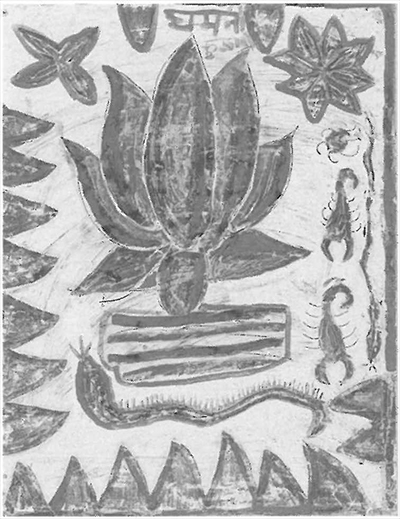

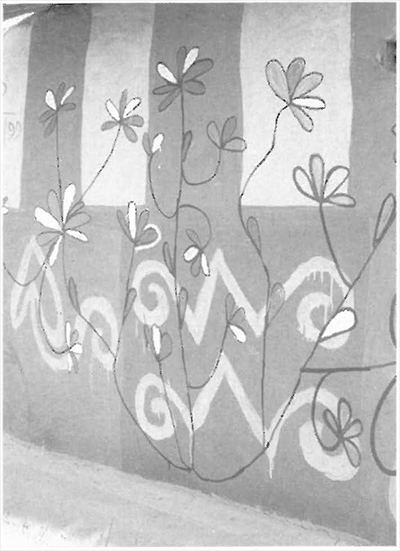

The Khovar women have been painting thick luscious murals on the walls of caves and houses since time immemorial. Portable versions of these works, especially paintings by Putti Ganju, Rukmani Devi and Ghamni Kumari cover the rituals of the seasons and of events, especially the all important marriage ceremonies. Their materials are those close at hand - clay, mud and vegetable pigments, but sometimes the blue of washing powder. The style is distinguished by broad sweeping lines, as though by a fine toothed brush. The tool is a nit comb, an implement familiar to parents of small children. The art that comes from this unlikely conjunction of media and tradition speaks of birds and jungle, of lotus flowers, cows, a celebration of the seasons of life.

If these minor variations on ancient sensibility are mild, the local graffiti art that joins them is best described as wild. This is the work of urban youth at its most intense, artists painting on forbidden walls. Or not so forbidden. For in Djamu the works of Balarinji Design turn rebels into artists. The most memorable of these graff writers, Haro, melds his wild words with elegant carvings tinted with paint. The resulting objects fit comfortably within the Maori visual tradition. But although he is proudly descended from the Maori people, Haro is not in the exhibition as a New Zealand blow-in. He learnt his art in Sydney, as a part of the dominant tribe of urban indigenous youth, a grouping often stigmatised as an underclass. By placing his work, and that of his colleagues, here in a privileged museum space, the visitor is reminded of the fluidity of visual traditions, that yesterday's graffiti is today's high art. And that today's renegade is tomorrow's cultural hero.