After East Timor got its independence, after the New Order regime resigned, after the resurgence of democracy, after General Wiranto was dismissed - what remains for Indonesia? Disintegration is still threatening. The problems are overwhelming. Aceh is in revolt. There are demands for local autonomy. The economy is in crisis with unemployment, a ruined environment, an ever-widening social gap between rich and poor, violent clashes between people of different ethnicity and religion, all coloured by widespread official corruption.

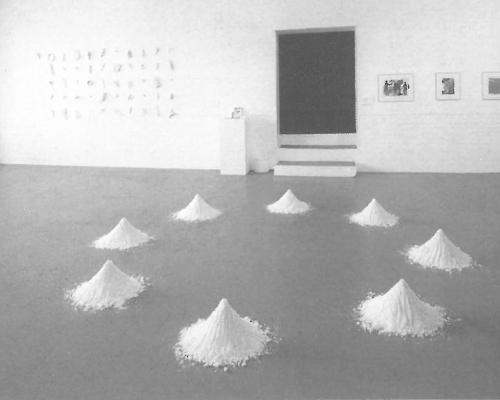

Indonesia, along with its more than 200 million inhabitants, has long been a 'repository of problems' in Southeast Asia. This status is reflected by the works of 14 contemporary artists at the Ivan Dougherty Gallery, UNSW College of Fine Arts, Sydney last March. Beware! Recent Art from Indonesia, originated in Melbourne and is currently touring Australia before travelling to Hiroshima and Berlin. Curated by Damon Moon, Alexandra Kuss, Dwi Marianto and Mella Jaarsma, the show is the biggest touring exhibition of recent Indonesian contemporary art practice ever to be shown in Australia. One of the aims of the exhibition is to draw attention to the art of Australia's close neighbour.

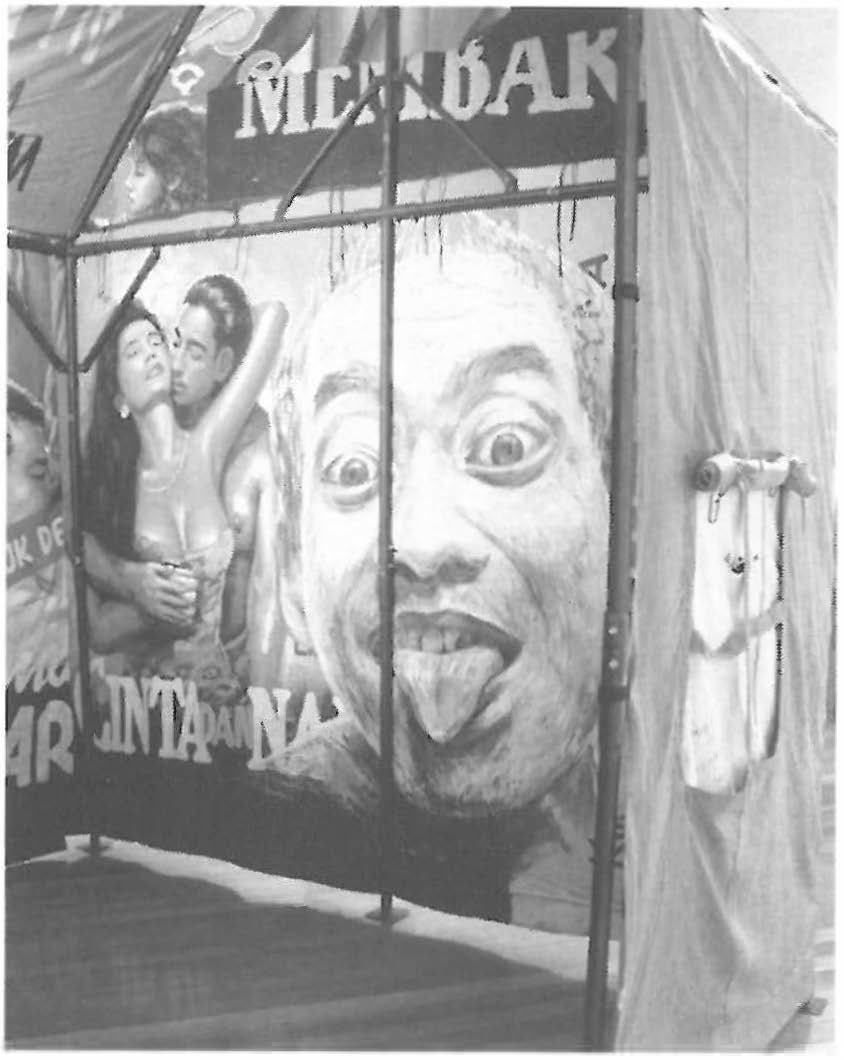

Most of the works presented in the exhibition are, as Dwi Marianto calls it, ledek ngeledek (in Javanese idiom this literally means "to tease or to provoke"). For example, Agus Suwage's work Pressure and Pleasure, is constructed from a military tent which could remind us of the frightening life experienced in Indonesia for the past few years. The glimpsed appearance of the work is similar to scenes often seen in much of the mass media. Suwage intends us to think that this scene, in which an Indonesian erotic film advertisement has been set and dangdut music can be heard, is real. We can hear the lullaby of Indonesian popular music, with its lulling and sentimental lyrics, contrasting with the military divan.

The artists want to tell us a story that, in the surrounding daily environment, as well in Jakarta, Yogyakarta and Bali - people still enjoy normal life. They shop in the malls guarded by the army men, trade among staged protesting demonstrators, and watch protestors clashing with the anti-riot policemen on the streets while watching TV (Hollywood films, MTV channel, soap operas interspersed with the politician's talk show and ads, disturbances in Aceh, or recent news from East Timor). Some daily scenes look paradoxical and contradictory compared with the way the media focuses only on the military relentlessness that depicts the common people as victims. In some ways, this media coverage also demonstrates the exotic appeal of Indonesia as commodity. Such a status has helped construct the opinions of public and international society.

Tisna Sanjaya's Visit Indonesia Year is another provocative piece, teasing the international media for the way it describes Indonesia. The emphasis on Indonesian political crises has had a far greater impact on the public image of the country than the Indonesian tourism campaign in 1990. Last year, when rioters swarmed in Jakarta streets, some 'tourist guides' allegedly profited from helping those international camera operators and press who were trapped with the street protesters. The guides were able to get the Westerners out of the military blockades and solve other problems. As many of the expatriate Westerners ran helter-skelter, interest in international tourism declined drastically.

Yet there was masses of publicity about Indonesia at that time. Thanks to crises! It could be said that, for the international community, the story of politics in Indonesia is as much an item of consumption as the exotic scenes at Kuta Beach in Bali; the deliciousness of sate kambing; or the aromatic Indonesian clove cigarettes. Agung Kurniawan's Souvenirs å la Third World is perhaps a case of the artist teasing himself and political activists. But his main target has to be the international press who always sell stories of Indonesian crises for their sensational impact and the satisfaction of international news consumers, whether on television or the banner headline on a morning paper.

It is understandable why these artists show such tendencies. It is a commonsense reaction. As well as most Indonesian people swayed by many problems, they feel bored at being an object for international spectators. Many of Indonesia's problems have not been solved and significant recoveries do not yet exist. Artists only try to relax and joke for a while, to cool their heads from stress. Meanwhile, another new generation has risen. They move and revolve without waiting for any signs. Change in Indonesia is faster than you have thought! I change therefore I am. Beware!