At the First Asia-Pacific Triennial Conference in 1993 Chinese artist and curator Xu Hong commented that if you "look at a leopard through a tube of bamboo, you see only one spot".[1] It is a significant fact that in the last decade Australia has had more exhibitions of contemporary Asian art and more cultural exchanges in contemporary art with Asia than has any Western country. The result has been the building of a superb network of contacts and of knowledge within Australia. As one example, Asialink alone has initiated 46 exhibitions of Asian art coming to Australia and of Australian art going to Asia.[2] The transformation in contemporary Asian literacy in Australia has operated at many levels and not simply in contemporary art. Neil Manton details the development of these cultural links in this issue of Artlink. When suggestions are made, as they are being made in the current political climate, of cutting back these programs in favour of more emphasis on North America and Europe, we should take into account that Australia's turn towards Asia has never involved turning our backs on North America and Europe, and that so often it is curators from those continents who, in seeking Asia contacts, now come to Australia, indicating the depth of knowledge that has developed here in a relatively short time.[3]

In this brief article I will focus on the Queensland Art Gallery's Asia-Pacific Triennial. From the first, the Asia-Pacific Triennial was conceived as more than an art exhibition and was equally about creating a network of contacts with artists and art institutions, a research base and permanent collection of contemporary Asian art and a forum for discussion of the art of the region. The project, always seen a a national project, has changed and evolved over the decade but this original conception encompassing three large-scale survey shows on the contemporary art of the Asia-Pacific has remained. A significant part of the Triennials has been the conferences. All three conferences, the largest art conferences ever held in Australia as Nicholas Jose has noted, were developed in conjunction with Griffith University's Centre for the Study of Australia-Asia Relations and the third conference also with the Humanities Research Centre/Centre for Cross-Cultural Research at the Australian National University.

The APT project originated in the late 1980s and early 1990s from a policy direction of the new Chairman of Trustees at the Queensland Art Gallery, Richard Austin. One of the early pioneers of Australia's post-war engagement with Asia, Austin's involvement with Asia began as a prisoner of war in Changi and on the Burma Railroad. The project achieved the strong backing of the then Queensland Premier, Wayne Goss, and it is the Queensland Government which has largely funded the three Asia-Pacific Triennials, together with the Australia Council, the Cultural Relations Program of the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, Foundations such as the Japan Foundation and commercial sponsors such as Singapore Airlines. The three Triennial exhibitions held in 1993, 1996 and 1999 have involved over 100 Australian and international curators, over 300 Asia-Pacific artists and over 350,000 visitors, closer to 400,000 with the Virtual Triennial and internet art programs.[4] The response to the exhibition has been particularly important. As Charles Green has noted "... a fiercely supportive Queensland audience has adopted the APT with great enthusiasm"[5] Critical opinion has been substantially positive with, for example, US critic Judith Stein noting in the June 1997 issue of Art in America "... it is clear that the Queensland Art Gallery's 'Asia-Pacific Triennial' series is affecting the global discourse of contemporary art".[6]

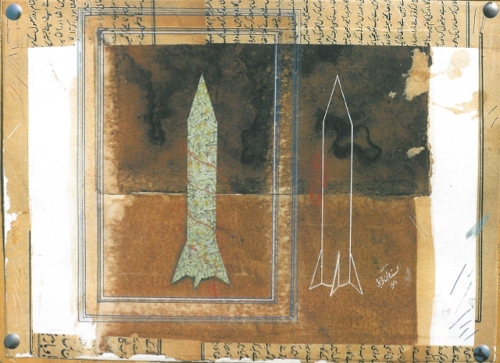

One of the most critical issues in contemporary Asian art, and one of early significance to the Triennials, is the continuing tension between intellectuals in the different countries of Asia and the West. Of course there is no such thing as "Asia," and one of the results of a decade of Asia-consciousness has been to inform Australians of the diversity of the different cultures of this dynamic region, as well as the changing nature of those cultures and societies. Australia itself is not the same country as it was ten years ago, and one factor is our new dialogue with our neighbours. One could suggest that there is no such thing as the West either and that the word has ceased to have a definite meaning except, as European historian John Gray has recently argued, in the United States.[7] The fact is Europe and North America have been slow to include contemporary Asian artists in major exhibitions although this is changing. Singaporean critic T.K. Sabapathy, writing in the Second Asia-Pacific Triennial catalogue, pointed out that there had been among speakers at the earlier 1993 conference "a wariness towards accepting or succumbing to orthodoxies emerging, imposed or acquired, from the West".[8] Indian critic Geeta Kapur in the same publication had memorably compared addressing US Americans on the question of Asian art with Australians as "like getting out of military fatigues and putting one's feet in the water;" but she went on to say: "This is on the pretext that Australia is Asia, which it is, and it isn't.".[9] Marian Pastor Roces from the Philippines in the first Triennial had already called for a new "calibrated terminology" in describing the art of the region "...that can perhaps go beyond the terms "syncretic",or even perhaps "hybrid", and certainly beyond that sad word 'influences'...".[10] Chinese critics Huang Zhuan and Hou Hanru had also in a number of publications voiced their determination to oppose Western cultural hegemonies.[11] Artist Xu Bing treated this issue brilliantly in a performance in Beijing in 1994 called "Cultural animals – a case study of transference," in which a pig whose body had been painted with Latin words, representing the West, was sexually mounted by a male pig whose body was covered with Chinese writing.

Australia has had the opportunity in the last decade to participate in these debates in a way that is open to new approaches to the art of the region. While the Asia-Pacific Triennials in 1993, 1996 and 1999 have only been one part of the multiplicity of projects undertaken in the decade, they provide an example of a new type of exhibition model, an essentially Australian approach, which could be described as invoking a grove of "tubes of bamboo" in a collaborative and collective manner in which the views of those in the region are equally important in determining content and focus. We accepted the early advice of one Southeast Asian critic who told us not to go into the countries of the region as mainly white Europeans, choosing only the art that interested us and an "international" ie. Western audience As I wrote in the first Asia-Pacific Triennial catalogue, while the APT had no theme it did have a thesis in that Euro-Americentric approaches were no longer valid in evaluating the art of this region.

One of the criticisms directed at the Asia-Pacific Triennial, for example from Julie Ewington, has been that it needs fewer curators, fewer artists and more focus. That may well be the future but the early exhibitions were unashamedly large-scale surveys, aimed at creating contacts at a time when few existed. In addition other projects have spun off from the APT - differently focussed conferences, a planned exhibition on Asian Modernism and on seminal figures in Asian and Pacific art,who have also been collected as part of the permanent collection. The Triennials were as much about building knowledge and hopefully enduring friendships as about selecting art for three exhibitions and in that sense they have undoubtedly succeeded.

Ben Genocchio, writing in The Australian last year, criticised what he described as a situation of four curators selecting three artists from Vietnam for the last exhibition. In the case of Vietnam, Ian Howard, tremendously knowledgeable about Vietnam from his years of working with that country, could easily have selected the art single handed, but he agreed to take a younger Australian curator in a mentoring role, and in Vietnam itself co-curator Dang Thi Khue, herself from the north, asked for another advisor to be included from the south, demonstrating the differences that still exist in Vietnam today. Mentoring and allowing younger curators from Australia and the Asia-Pacific to be part of the process has been one of the most important achievements of the APT. Another important factor has been the role of artists in helping shape and develop the project, including in a curatorial role, and of course ultimately the success of the APT has rested on those artists. Bringing such a large percentage of the artists to Australia to interact with communities here (communities as distant as Moree, Tasmania and Cooktown) has been a characteristic of the whole APT experience that has created much of the warmth and emotion with which participants and audiences embraced the project.

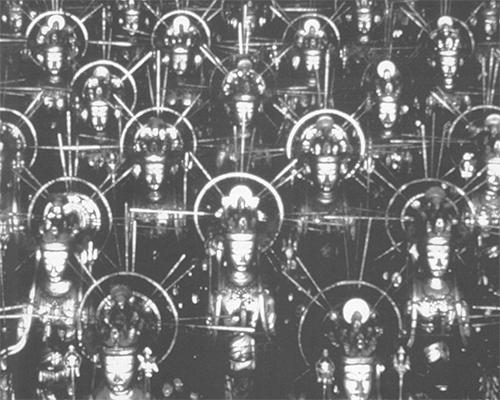

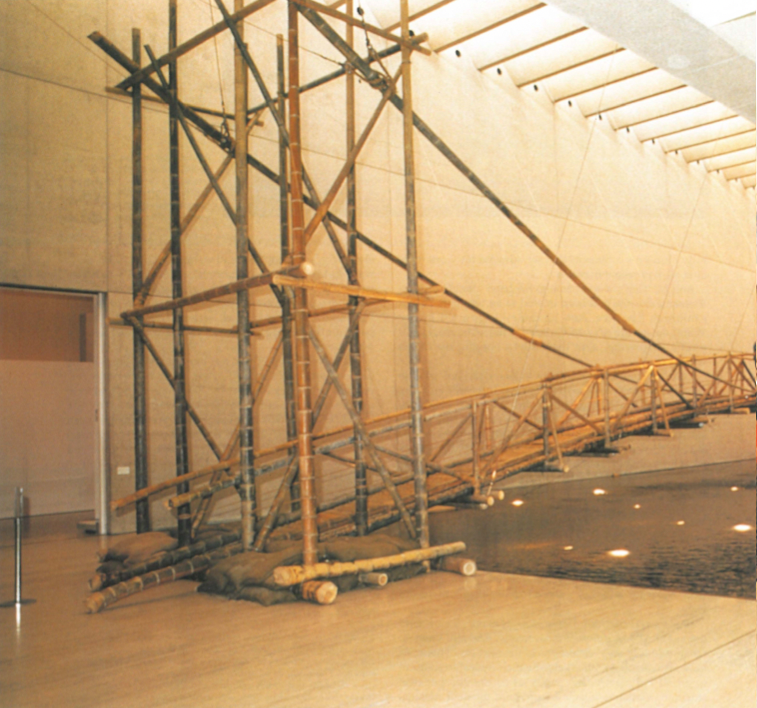

One of the most important facts about the Asia-Pacific Triennial has been that it is Asia-Pacific and not just Asian. (This issue of Artlink however focuses only on Asia.) The decision to include artists from Australia and particularly indigenous artists from Australia and the Pacific has been a critical one, and has made the APT exhibitions unique in world terms.[12] This has allowed, when selecting Asian art, curatorial perspectives that have encompassed, for example, a tribal artist from India, Sonabai; artists dealing with indigenous issues from the Philippines including Santiago Bose and John Frank Sabado; Dang Thi Khue's connections with minority artists in Vietnam; and collaborations such as the exciting work of the Indonesian Brahma Tirta Sari studio and Utopia batik Aboriginal artists from Central Australia.

Much of the art in the Triennials has been art less concerned with national art movements or artists representing countries than art which is about societal change and the personal idealism of artists to contribute to their communities building new futures. The voices of the artists and the writers from the region at the various APT forums have not always been optimistic about the future but they have indicated a belief in the role of art and artists in connecting and sustaining communities. This has not been confined to artists. The "kid's apt" an innovation of the last exhibition was unashamedly a personal response on my part to Pauline Hanson's "Young Nation".Over 30,000 children from 3 to 12 years old participated, proving that their parents believe in continuing to learn about our neighbours.

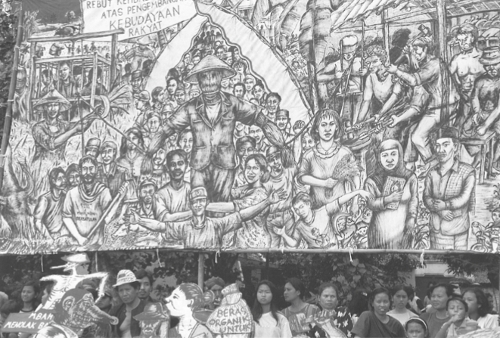

The articles in this edition of Artlink by Chinese writers Oscar Ho, a Hong Kong based curator, and Sang Ye, who left China for Australia during the decade and who is part of what could be called the "fourth" China of the post-Tienanmen diaspora, reveal an element of disillusionment regarding contemporary Chinese art. In Indonesia, however, the events of the last year have again brought highly politically charged art with collective purpose to the forefront and art into the streets. Art concerned with social transformation and injustice has been foregrounded in all the APT exhibitions and perhaps nowhere more strongly than in the work of Indonesian artists, which has connected with audiences in Australia over the decade in a most extraordinary way. One example is the work of Dadang Christanto. In the first Triennial, hundreds of flowers and poems were left in front of his lament for all the dead

"For those: who are poor, who are suffering, who are oppressed, who are voiceless, who are powerless, who are burdened, who are the victims of violence & who are the victims of injustice;"

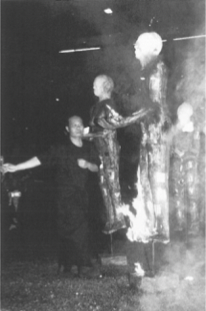

and his moving performance at the Third Asia-Pacific Triennial "Api di bulan mei," (Fire in May about the events in Indonesia) in which he burned 47 papier-life-size human figures, came at the height of uncertainties during the Timor crisis. The Indonesian artists' works reflected their courage over decades, but one Australian academic faxed us from Perth to close "their" work and indeed the whole show down. As one young Australian artist said to me at the time, events like the APT and engagements with Asia are more important to Australia than ever now. Yes, and also more challenging.

Whatever the future of projects such as the Asia-Pacific Triennials, they need to retain their idealistic commitment to collaborations based on mutual respect between the hundreds of artists, critics, curators and writers in the Asia-Pacific who, over the decade, have brought a multitude of tubes of bamboo together in the collective and often risk-taking engagements of Australians with the contemporary art of the Asian region and in the process changed the way many Australians see ourselves.

Footnotes

- ^ Xu Hong unpublished paper First Asia-Pacific Triennial conference, September 1993See also Xu Hong 'Modern Chinese Art' in Caroline Turner (ed), Tradition and Change: Contemporary Art of Asia and the Pacific, University of Queensland Press, 1993

- ^ Since 1991 Asialink under Alison Carroll's direction of the Visual Art Program has been involved with 46 exhibitions touring to 151 venues showing the work of 325 artists and has selected 181 artists and art managers for residencies during this period. To date Asialink Arts has worked with 19 countries in Asia including: Bangladesh, Brunei, Burma, Cambodia, China, India, Indonesia, Japan, Korea, Laos, Malaysia, Nepal, Pakistan, Philippines, Singapore, Sri Lanka, Taiwan, Thailand and Vietnam.

- ^ In the art field alone these have included Australia Council initiatives and numerous exhibitions. Beginning with the Queensland Art Gallery's Japanese ways: Western means: art of the 1980s in Japan in 1989, major exhibitions at Australian art museums have included Zones of Love, anexhibition of contemporary Japanese art at the MCA Sydney in 1991- 92; Mao goes pop focussing on contemporary Chinese art, again at the MCA in 1993; India Songs at the Art Gallery of New South Wales, also in 1993; Claire Roberts' exhibition New art from China in 1992/93: ArtTaiwan at the MCA and in Wollongong in 1995; and the three Asia Pacific Triennial exhibitions in 1993, 1996 and 1999. Artist exchanges include continuation of the important ARX in Perth and artist-in residence programs at Australian universities, as well as Asian artists represented in the Sydney Biennales and more recently the Melbourne Biennale, and the pioneering programs of Asialink. In the last five years, there has been a plethora of Asian art exhibitions at state, regional and university art museums in Australia, culminating in the exhibition of contemporary Chinese art Inside Out, currently at the National Gallery of Australia.

- ^ The Triennial was developed with the assistance of a National Committee: Doug Hall and Caroline Turner from the Queensland Art Gallery, Alison Carroll from Asialink, Neil Manton, formerly with DFAT, David Williams, Director of the Canberra School of Art, with Ian Howard, then Director of the Queensland College of Art and Margo Neale, then Curator of Indigenous Art at the Queensland Art Gallery joining the National Committee in 1996. Senior Project Officer Rhana Devenport, Project Officers Christine Clark and Dionissia Giakoumi, Assistant Curator Suhanya Raffel, as well as Head of Exhibitions Andrew Clark, deserve special mention, as do Triennial Curators Anne Kirker, Pat Hoffie and Claire Roberts. The APT has had extraordinary support from Queensland Art Gallery staff and from art professionals nationally and internationally.

- ^ Charles Green, 'Beyond the Future: The Third Asia-Pacific Triennial' Art Journal, New York vol 58 no4 Winter 1999, p. 81

- ^ For a discussion of the Judith Stein quote see Caroline Turner, 'Art Speaking for Humanity: The Asia-Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art' Art Journal, New York vol 59 no 1 Spring 2000, pp18-19

- ^ John Gray, False Dawn: The Delusions of Global Capitalisms Granta Books, London 1999, (first pub 1998) p.216

- ^ T.K. Sabapathy 'Developing Regional Perspectives in South-East Asian Art Historiography' Second Asia-Pacific Triennial catalogue, Brisbane, 1996 p. 13

- ^ Geeta Kapur, 'Two or Three Things about Ourselves' Second Asia Pacific Triennial catalogue, p.22

- ^ Quoted in Sabapathy, op. cit.

- ^ Quoted in Claire Roberts 'The Revolution Reinvigorated: Art as Cultural Strategy Chinese Art in the 1990s' Second Asia-Pacific Triennial catalogue, p.40

- ^ The importance of a conjunction of indigenous Australian art and Asian art first occurred to me travelling in China in 1984 with Oodgeroo (Kath Walker) and seeing her dynamic dialogue with Chinese art. Her death in September 1993 sadly prevented a visit by all the APT artists to her Stradbroke Island home.