Celebrating The Exquisite Corpse is a large group show of forty collaborative artworks by 120 artists from Victoria based upon the eponymous picture game (played in the manner of the word game Consequences) where a figurative drawing is built up by a succession of artists who cannot see the previous drawing. The game was typical of Surrealism's interest in automatic and random processes of creativity. Sheets of paper and half-completed drawings were dispatched by the gallery around a group of artists who were mostly sourced through an advertisement in Art Almanac asking for artists to register their interest in the project, taking a cue from the democratic aspects of the Surrealist inheritance to generate a serendipitous response. Some artists nominated friends and associates as appropriate to come on board and others were chance marriages made on the grounds of the date of registering interest in the project. The visual experience held together surprisingly well for a show that was conjured out of a curatorial idea and the theory was validated. The works created for the show were neither gimmicky, grotesque nor incoherent and all maintained a sense of both visual and conceptual integrity. Overall the exhibition was more complex and theoretically relevant than the plethora of painted fridges, boots and cellos that seem to form the basis of novelty visual arts exhibitions. In fact some groups of drawings worked so well that a viewer could suspect that some degree of exquisite cheating had gone on – although all the artists assured the curator that it had not.

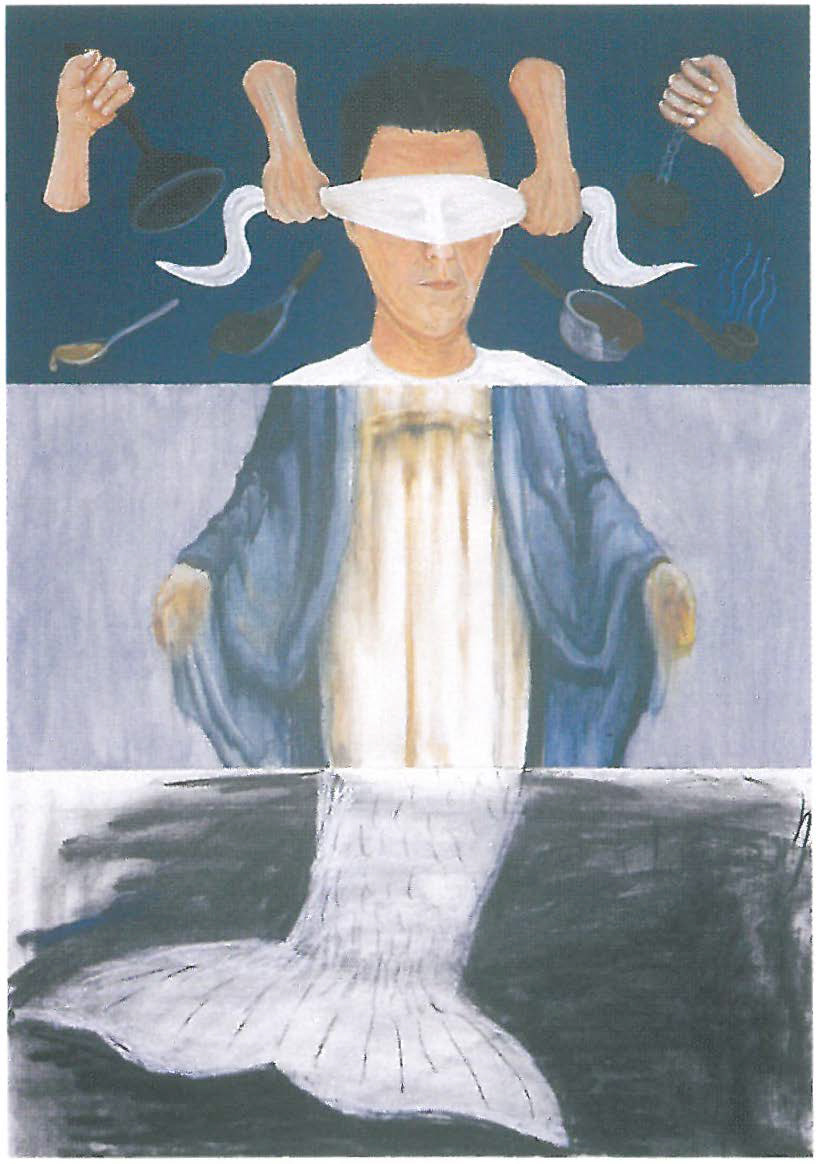

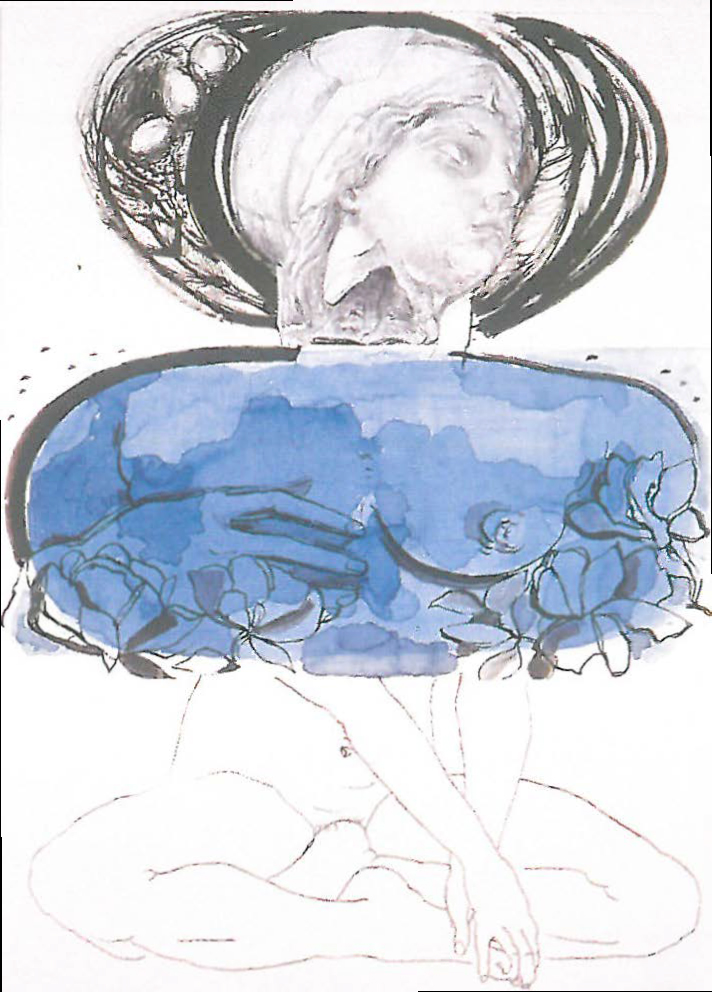

Unlike many similar projects the contributed items had a recognizable rather than an opportunistic relationship to the bulk of each artist's practice. Particularly suprising and effective was the level of consistent internal balance achieved in the works, between the different weighting and density of mark-making. Equally credible was the conceptual balance that developed within each work between the very different approaches to the brief, though the greater majority of the artists interpreted the idea of the corpse in the title literally and drew human figures in varying manners. In many cases the more obvious disjunctions between styles served to create a more complex conceptual weighting of content.

Celebrating the Exquisite Corpse is testament to several ongoing facts about arts practice in Victoria. Firstly it documents the de facto centrality of surrealist values in tertiary art education since the 1970s since such a wide range of artists was able to immediately grasp the idea and run with it due to prior knowledge of Surrealist practice and events. Secondly it demonstrates artists' persistent validation of drawing and intimate mark-making on paper against more formal and finished media, although the mark-making was not only drawing, including digital printouts and collages and embroidery onto paper – all except one digital piece using the paper supplied. Technical details meant that paper of the same size more suited to the chosen printer was substituted. Thirdly it celebrates the phenomenon of 120 professional visual artists in the state of Victoria, working in various styles and including both metropolitan and regional artists, emerging and senior artists, celebrated and overlooked, a body frozen in the Pompeiian ash of a given moment, yet refreshingly without any moral guardianship or heavy handed information delivery. Identifying the artists without reading the labels tested any viewer's expertise.

Individually the works could be read so well between three different hands because they frequently referenced ideas and mannerisms that are currently in the ether and shared by many artists. Thus a sense of cohesiveness was reinforced. Feminist theories of the body and their placements in the artistic canon were an effective vein of imagery. One of the most rewarding was Drawing Twenty Seven by Rosslynd Piggott, Adriane Strampp and Steig Persson in which both the popularity of such ideas and explicit links between present day understandings of feminism and surrealism were evident. The popularity of child-like expressionist modes of drawing also ran through a number of other works. Likewise the copying of old technical, scientific and anatomical prints formed another subset of visual language, possibly representing the original surrealists' use of 19th century illustrations. Religion, the sacred, the bizarre, the nostalgic, desire, echoes of the Baroque and the Renaissance appeared again and again and made The Exquisite Corpse a consciously poetical exhibition without being mawkish or forced. Some of the most effective works were a surprising conjunction of names. Ron Greenaway (Drawing Twenty Nine) is an artist who for some decades has been working in a manner that was steeped in the ethos of the original surrealist movement and his contribution neatly matched the personal art history of his ongoing pictorial concerns – even though Greenaway as an artist who abjures the written word about art no doubt will not care much for the opinion of a mere writer. Maggie McCormick's The Corpse is Dead (Drawing Thirty Two) was a perfect feminist satire, a newspaper announcing that the greatest woman artist of the 20th century had been unmasked: Rose Selavy in her masculine drag of Marcel Duchamp had been rated as the father of Conceptual Art and Surrealism without anyone realising that this male leader was a woman. Nothing matched it for sheer cleverness, historical savvy and the knowing re-encapsulation of the historical movement of surrealism together with a feminist message about representation and voicing in art history.

The dispersal of Celebrating the Exquisite Corpse will be equally random. After a number of showings in public venues around the state in the next year or so, the drawings will be distributed amongst the collections of the Regional Galleries of Victoria.