Despite protestations otherwise, the timing of these concurrent exhibitions could not have been better. The 'coincidence' in programming which saw the independent exhibitions, Illuminating Evidence and Watermarks: Crossings, appear during the Geelong Gallery's initial phase of refurbishment, poignantly serve to reflect on the gallery's collection and its broader context as an institution for its region.

Exploring in turn the inner and outer worlds, the installations rely on photographic documentation as a tool for what becomes the presiding theme: re-presentation, and the interplay between physical evidence and history. Carolyn Lewens and Neil Stanyer worked collaboratively on the concept and execution of Watermarks: Crossings, the second exhibition in a series of installations that explore water issues at regional Victorian sites. The first exhibition, Watermarks: Confluence, was held at Warnambool Art Gallery in 1999; the third centres on the Murray River and is currently on show at the Albury Regional Art Gallery. Illuminating Evidence marks the second time Felicity Spear and Sarah Winfrey have worked together. Each artist brings a distinctive but complementary line of enquiry to the project.

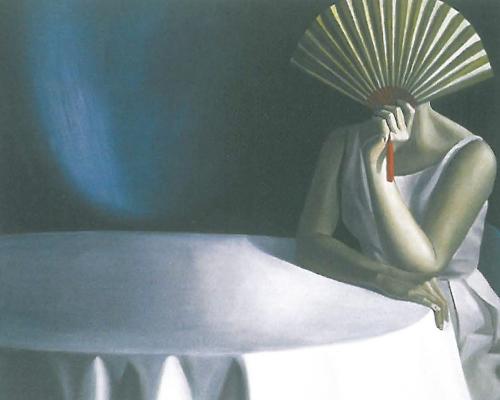

Winfrey and Spear use technologies old and new to refocus the space of the Gallery and part of its collection. Winfrey takes the familiar beat of revered domestic icons (cups, urns, plates and cutlery) and through careful manipulation, makes them lyrically sway and resonate. The incongruity of viewing digitally composed inkjet prints, backlit and contained within traditionally styled timber display cabinets, is curiously pleasing. Winfrey uses mirrors to calculatingly repeat the images so that each installation both recalls and reinvents traditional museum display practices. Her Between Order and Chaos is a crafty commentary on the very notion of collecting and the plaudits of order and ritual that museums preserve. Archival Evidence: Installed Room made me feel as if I was poking around in someone's cupboards, only to find, with relief, that they contained nothing sinister. The doors revealed backlit prints of carefully manipulated radiographs. The subjects: keys, light switches and garments are ordinary objects made newly extraordinary.

Felicity Spear zooms out from this almost forensic exactitude, and takes stock of the Gallery itself. It's a cunningly simple idea: a fish-eye view of the space you're already standing in. The pin-hole camera photographs hark very obviously back to times past, and in themselves say little. Considered with the lengthy text panels describing the photographic technique, they are pleasing enough. But as a series, and together with her three wrapped columns, they resound of the temporary nature of history, reminders of how the passage of time is sometimes only relevant when remembered. Importantly, each label cites the exposure time, ranging from ninety seconds to six hours in duration. While I remained oblivious to the nature and design of the gallery upgrade, taking in Spear's photographs was a bit like sensing a ghost, a relic of a life or era now finished. Equally, as the only viewer at the time, I felt (perhaps a little too nostalgically) as if I was privy to another memorial snapshot of the next moment in that history. Spear's Evidence series of silver gelatin prints reflects on other moments. The six tiny works pluck out snippets of the gallery ritual: a gallery wall, an open book, paintings on racks, boxed postcards, boxes of books and wrapping plastic, all poised for the next implication.

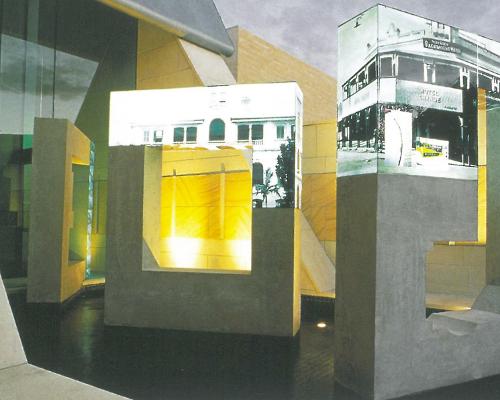

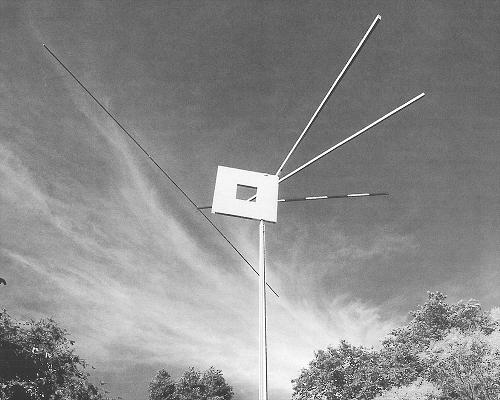

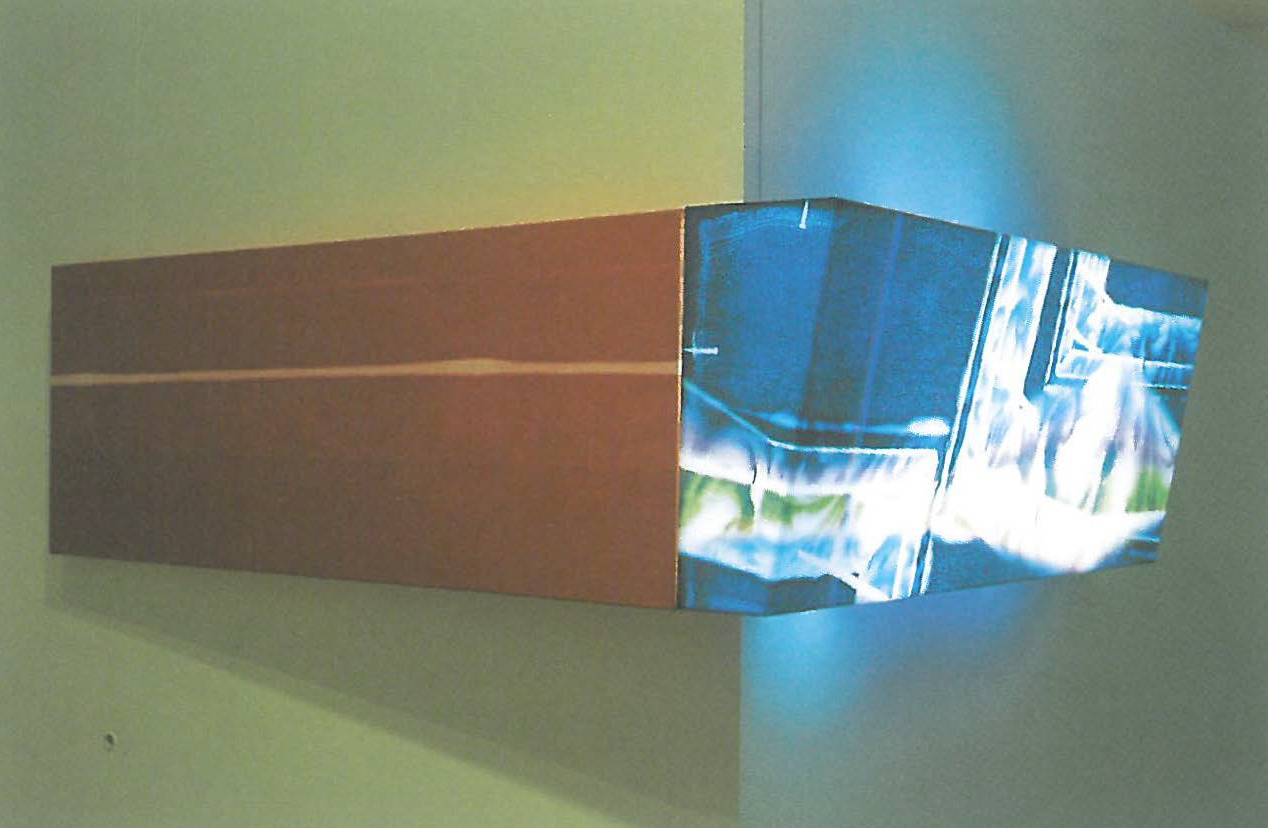

In Watermarks: Crossings, specific aspects of the local landscape are re-presented to reference other forms of temporality. The impetus for this exhibition is the history and development of Geelong's Barwon River. The river is the subject of one of the Gallery's most celebrated paintings by Eugene von Guerard, and the 1860 oil painting appears in the installation. But three bridges overwhelm the display: the LaTrobe Terrace fly-over, the McIntyre pedestrian bridge, and the decommissioned and concrete-cancer ridden Ovoid Sewer Aqueduct. Change and the march of time are again omnipresent. Lewens and Stanyer's vast photographs are testimony to the history and function of bridge building, and offer perspective, literally and figuratively, on the changing vision of this landscape.

The whole display is cleverly and selectively supplemented. One sound installation makes just perceptible the hum of cars and trucks on the fly-over. Another, a soundscape from within the steel pipes of the McIntyre footbridge, sounds like a didgeridoo. It is a gentle pointer to the alternate purpose of the river for the Wathaurong Aborigines, and a counterpoint to the imperial history. A cyanotype photograph (a nineteenth century process) of a rubbing of a commemorative plaque is an apt confluence of history. Nature's own detail is not neglected. Photograms of delicate riverside 'water-ribbons' are printed on suitably filmy fabric and allowed to gently move in their new environment. They are an eerie memory of the plant. As each aspect of the exhibition is absorbed, the layers of metaphor build to convey and confirm the artists' rationale.

Both exhibitions challenge the way we look. By cross-referencing past and present, via a decidedly patterned viewing process, spaces and icons are carefully selected, edited and refined to create stories. There are, however, numerous possible and accumulative narratives. Neither installation has a sense of start and finish. Instead, there is a choice of paths through the landmarks.