For women artists of the 20th century, the '50s and '60s were the hardest decades. The gains of the early decades of the century were eroded in the aftermath of World War II and the feminist revolution of the '70s was yet to come. The few women who managed to achieve a serious reputation did so against all odds.

Wendy Paramor's initial success (and her later effective erasure) has to be seen in this context. In her youth Paramor exhibited with the boys, went to London, travelled, held critically acclaimed solo exhibitions - and was one of only three women included in The Field, the memorable opening exhibition for the National Gallery of Victoria. But then, so sadly, she died. Even before her illness Paramor had moved away from the markers of masculine success. She had a child, before it was fashionable to have a child alone, at a time when there was minimal support for single parents. She moved to the west of Sydney to Hoxton Park, a spectacularly unfashionable address. Her initial reputation was supported by the lads who gravitated around the slick masking tape and airbrush style of the Central Street artists. They were less sympathetic to her new concerns of intimacy, growth and the beauty of transient life. So as her life faded, so did her reputation, it seemed as fleeting as the life of one of the bush crickets in her last drawings.

By 1975, when she died, the bright clean lines of the hard edge painting and sculpture which characterise the best of her oeuvre had also passed their use-by date. Her fellow artists had moved into careers in advertising or art schools. There was no market for clean-cut forms by a dead woman. Instead, new art was increasingly hand-made, intimate and personal. The kind of art that could have been made by a single mother in Sydney's west Paramor: Lost and Found is both an affectionate recovery of Paramor's reputation as an artist, and an exhibition which raises questions on the nature of artists' retrospectives. There is a sense of an artist in tune with the spirit of the times, yet moving always to find her own voice, her own interpretation of the dominant mood.

Her earliest paintings reflect the fluid Sydney style abstraction that is also seen in the late 1950s work of Brett Whiteley, Robert Hughes and Charles Reddington. Then there are the London works, and the thin paint of the student years gives way to confident sensuality. This is a painter entering her maturity with style. Some of the most beautiful works of this period are the drawings, which first show her authoritative sparse line.

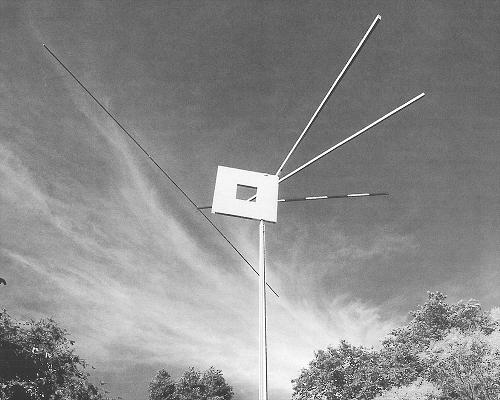

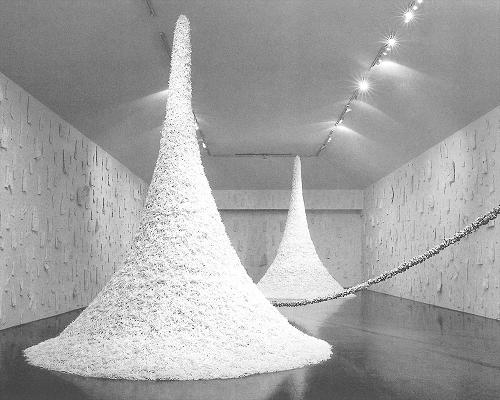

It is this sense of line that informs her next phase as she painted hard-edge works which are part of the style that clean-swept avant garde taste in the last years of the 1960s. Paramor turned to sculpture as well as painting, making bold forms that add a sense of touch as well as shape, colour and line. One of the great pleasures of the current exhibition is her 1967 series of clothing designs which have been realised into actual dresses - their refined brief lines evoke the world of eyeliner, pallid lipstick, Mary Quant and Courrèges.

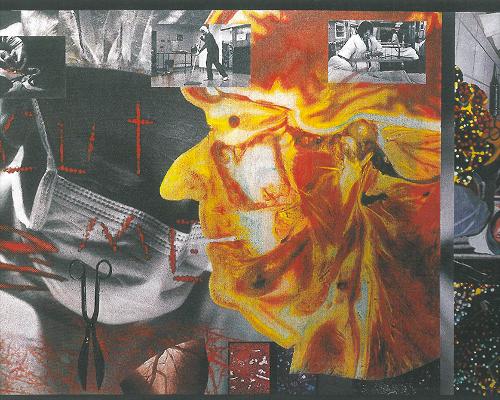

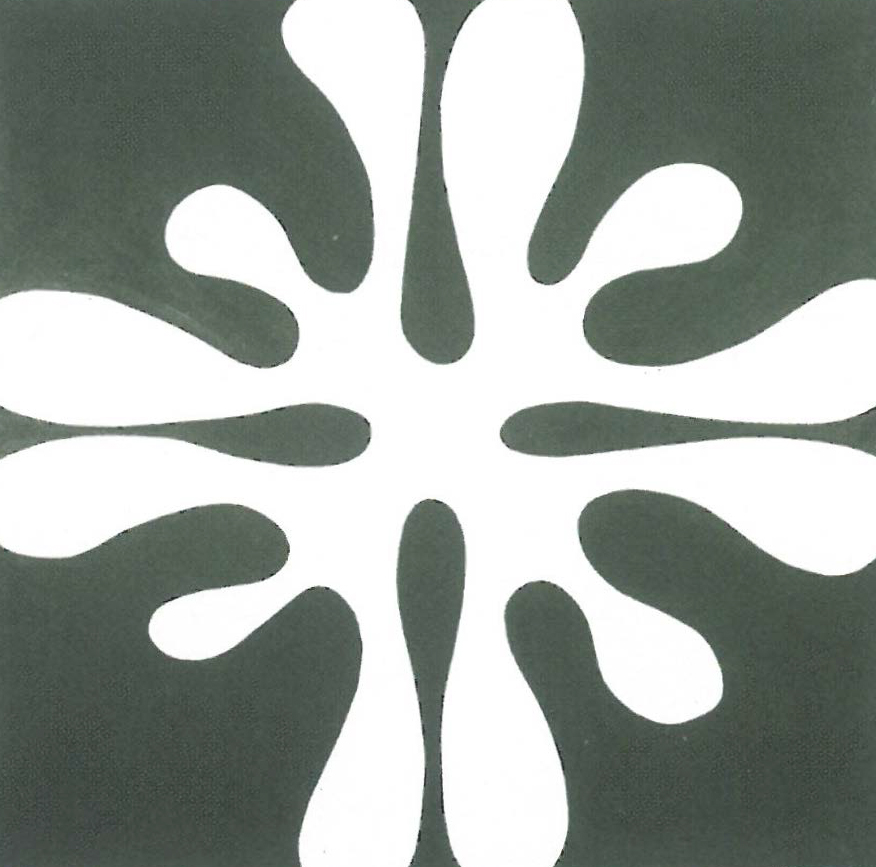

The paintings are tough yet complex. There are touches of whimsy in Manny (1968) where one solid form contrasts in a parade of translucent shapes. She encapsulates all the strength and extravagance of the 1960s in an untitled black and white painting which almost parodies Mary Quant's trademark flower. Her sculptures in clear seductive colours have the meandering geometry of a children's playground - yet no one could call these works "pretty".

Many of the works on view are in a shocking condition. Their state of disrepair reinforces the argument that the exhibition is but a part of the recovery of a lost reputation. Those who wish to see their art always perfect will wince at the scratches, flakes and dents in the canvases, the faded paper of the drawings. But there is no sense in just showing an airbrushed vision of art history. When reputations go, the physical works of the artist also fall into disregard.

The full range of Paramor's art also lets the viewer see the different strands of her career. The experimenting student becomes the confident artist, then fades away. The artist draws landscape, emotions, and pure form. There is a direct visual link between her last, fragile drawings and the early light lines affectionately describing an old wooden cottage.

By presenting this range of Paramor's work the curator, Cecily Briggs, both shows the fragile nature of the artist's reputation and implies a comment on one of Alan Oldfield's concluding remarks in his generous catalogue essay. As part of a 1971 exhibition at Central Street, Paramor submitted:

a suite of photographs of her young son - 'happy snaps', if you like - haphazardly arranged on a sheet of brightly coloured cardboard. It looked astonishingly amateurish and out of place among the stylish images supplied by her co-exhibitors. And the photographs were so personal for someone who valued her privacy.."

In the following years, as Paramor was leaving life, a new generation of artists was moving towards intimacy and domesticity. Once again, Paramor caught the tempo of her time but she came too soon to be noticed.