It is difficult to take seriously this Olympic Arts Festival exhibition's attempt to divine iconic points of intersection between art history and a nation's collective imagination. A case in point is the inclusion of Yolngu Aboriginal artists Mawalan Marika and Munggurrawuy Yunupingu in the selection of 'icons'. Part of the problem rests with the word 'icon', overused almost to the point of meaninglessness.

Columnist Tony Stephens noted at the time in the Sydney Morning Herald: "Icons are breaking out all over. They are so common these days that it is not enough to be an ordinary icon." His checklist includes 'great' icons such as the Sydney Opera House and Vegemite alongside more 'ordinary' references ranging from actor Jennifer Aniston to Tim Tams and a four-wheel drive. Clearly, Olympic City state art galleries are not above injecting a dose of tabloid-promotional hype into their thinking but the word and the concept do strike a curious paradox in the display of these two artists' work.

On the one hand, Mawalan (c.1908-67) and Munggurrawuy (c.1907-78) can hardly be called Australian icons. Few Australians would be able to pronounce their names let alone recognise them, and I have seen them included only in one dictionary or encyclopedia of Australian art. That's not to say that these artists shouldn't be iconised or that their place be given to more prominent Aboriginal artists. The exhibition's race and gender debt to dead white males could have been redeemed somewhat with the inclusion of Emily Kame Kngwarray or Tracey Moffatt or indeed more famous bark painters such as Billy Yirawala (one of the first to be honoured with a monograph), George Milpurrurru, John Mawurndjul or David Malangi. However, as the exhibition's subtitle reminds us, these 20 artists are from the AGNSW's own collection which, according to Ken Watson, Yiribana Gallery's assistant curator, restricted the choice to three Aboriginal artists. In stature and acquisition numbers, Rover Thomas was the only other possible inclusion.

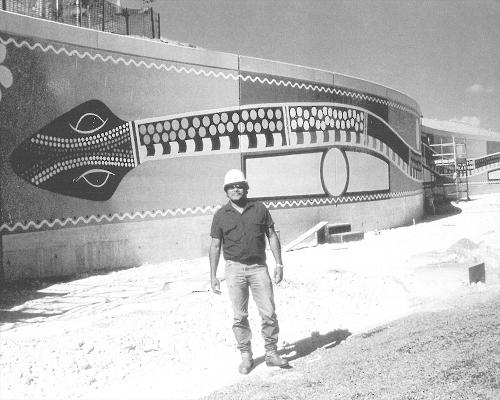

Sticking with Mawalan and Munggurrawuy pays tribute to their respective Dhuwa and Yiritja moiety and clan status as important ceremonial men. It also honours Dr Stuart Scougall (1889-1964), the collector-donor who, along with the AGNSW's then assistant director, Tony Tuckson, commissioned the epic bark paintings series at Yirrkala in 1959. Scougall justifiably regarded this commission as "the first time such a collection of bark paintings was made in a pictorial ballad sequence whereas other collections have been essentially sporadic, of a piecemeal nature". The artists' innovative role in this commission is acknowledged in the wall text's description of them as "one of the generation of artists who developed serialisation of the ancestral narratives into discrete episodes."

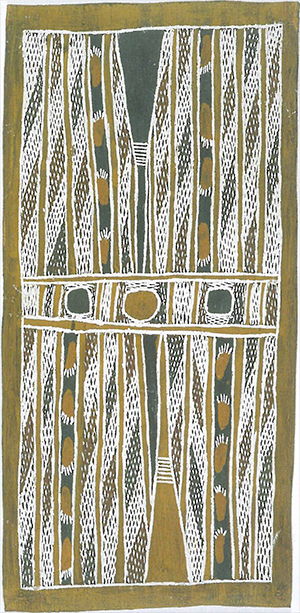

In these larger bark paintings on display Mawalan depicts the complex Djang'kawu -Wawilak ancestral creation narratives and Munggurrawuy various clan versions of the equally complex and ritual-based Barama -Lany'tung mythology. Also displayed are painted and ceremonially decorated wooden sculptural depictions of these primary ancestral beings. The misnomer 'icon' is more apparent here considering that one of the Djang'kawu figures collected by Scougall in 1960 is attributed to Mawalan's younger brother, Mathaman, who is not mentioned in any publicity or reviews to date. Similarly, the so-called Djang'kawu Creation Story 1 1959*, the first attributed work from Yirrkala in the gallery's acquisition catalogues, is a collaboration of four artists: Mawalan (who supervised), Mathaman, Wandjuk (Mawalan's son) and Woreimo (same moiety but different clan). Scougall and his then secretary Dorothy Bennett were unusually thorough in documenting provenance details including artists' names. Scougall's reasoning to Harry Giese (the NT Welfare Director who authorised his collecting trips) was that the buyers demanded it, but as Margaret Tuckson who accompanied her husband and Scougall on two commissioning trips confides, it was more to do with bestowing dignity. In one of Mawalan's sculptures his own name appears in big black capital letters along the back of the figure's leg - a potent reminder of both artists' seminal roles in the nascent Aboriginal art 'boom'.

An apt criticism of the exhibition from Humphrey McQueen is its failure to differentiate between the artist as icon and the iconic nature of their work. "Icons are images, not people," he writes (Art Monthly September 2000). This last statement doesn't hold up too well amidst the cult of celebrity and its most recent global spectacle with Aboriginal athlete (and Sydney Olympic icon) Cathy Freeman's lighting of the Olympic cauldron. With Mawalan and Munggurrawuy, however, the iconic status of their imagery accurately reflects its spiritual depth. As images of religious instruction and devotion, the sculptures and epic bark paintings are icons of Yolngu ancestral law. In an analogy that may have pleased the Scotsman in Scougall, Howard Morphy compared Mawalan's rarrk (cross-hatching) configurations to tartan designs, which likewise herald ancestral clan affiliations. Both Mawalan's and Munggurrawuy's distinctive clan designs are also expressions of a classic Arnhem Land Aboriginal iconography whose appropriation - from the work of Lin Onus at one end to mass-produced 'Australiana' at the other - represents another valid though highly problematic level of iconisation.

While the other artists were represented with a reasonable span of work, the 30-plus-year careers of Munggurrawuy and Mawalan as 'artists' in a Western sense were telescoped into three years with works from 1959-61. Having promoted them as icons does this mean the AGNSW's Australian art curatorium will eventually honour these Yolngu artists with the retrospectives they're yet to have? In the exhibition's loose chronological hang, the two Yolngu artists (though technically, five) also seemed to lose out, tucked away in a space smaller than that allocated to some individual artists. Yet the iconic presence of Mawalan's Djang'kawu Story 1959, probably the smallest work in the show at 35.9 x 17.5cm, proved that size doesn't matter.

Its subject - trepang, trade and Djang'kawu moving the mythical Baijini on from spoiling a sacred site (Yalanbara) - glimpses the fascinating (pre-colonial) drama of Yolngu and Top End Aboriginal contact history. Munggurrawuy's father, Amalatja, had travelled to Indonesian Macassar (Sulawesi) and the Baijini people are believed to symbolise visiting Dutch or Portuguese. In this story their footprints signify retreat.