In Talking Together Lola Greeno has brought together a diverse group of indigenous artists "for the expression of ideas and the exchange of knowledge and skills in Aboriginal art" (Greeno). Geographically the list extends from Western Australia, then Darwin and Melville Island in the Northern Territory, via Melbourne to Cape Barren Island, Flinders Island and Burnie in northern Tasmania.

"Conversations between artworks" reads the subtitle of the catalogue essay by Julie Gough. But if there was any talking, it was obvious there were several different languages being used – after all, "traditions (in making) are not fixed forever in time." (Greeno) and the works certainly demonstrated an extensive use of different processes.

For the viewer, however, eavesdropping in on a conversation like this – where there is a wide range of stylistic approaches to making and to staking cultural claims – was more like walking unawares into a gathering where the speaking in tongues celebrated a commonality of purpose.

The place of this congregation – the University Gallery, Launceston – had been purpose-transformed for the event. As if dared to commit an extreme act of bravado, the Gallery's longest wall, the one that the visitor first sees on entering, had transformed itself by assuming a luminously aqua green sheen. It sang, siren-like, to a mustardy ochre familiar opposite.

.jpg)

If a unifying curatorial theme was not immediately apparent, it was because of this audacious intervention between the art works and the viewer. After recovering from the shock – in some ways a pleasurable visual experience – I had to ask if one could see the art works for the walls? Or could you see them better? It was as though we were made to seriously question why gallery walls are nearly always white!

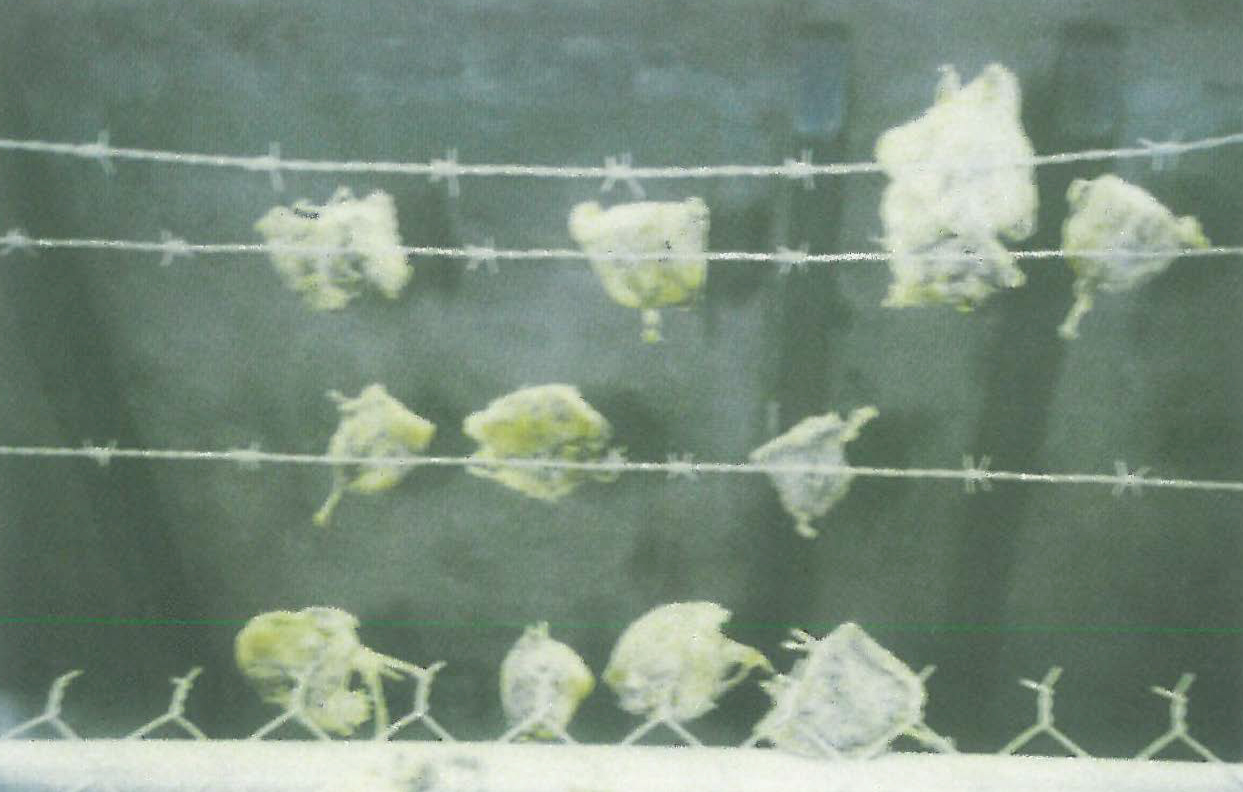

On the safer brown-orange, mustard walls were the laser prints from Polaroid photographs, taken by Destiny Deacon in 1995 during a visit to Launceston. One of her subjects is mutton-birds. The poor creatures (headless and cooked) are shown in various shenanigans at the School of Art in Launceston, as if reclaiming a cultural position in an institutional setting of Eurocentric learning. The intrusive coloured wall actually pushed the grey tones of these images forward, increasing their playful irony.

Similarly, the critical observation Nennerpertenenner (Sammy Howard) makes on the colonisation of the Pieman River (northwest Tasmania) in his innovative ceramic relief sculpture, is, arguably, intensified. The adjoining mustard wall also provided an oddly sympathetic background to Thecla Bernadette Puruntatameri's accomplished repeat fabric print of mud mussels, and to Francesca Puruntatameri's acrylic painting, Kulama.

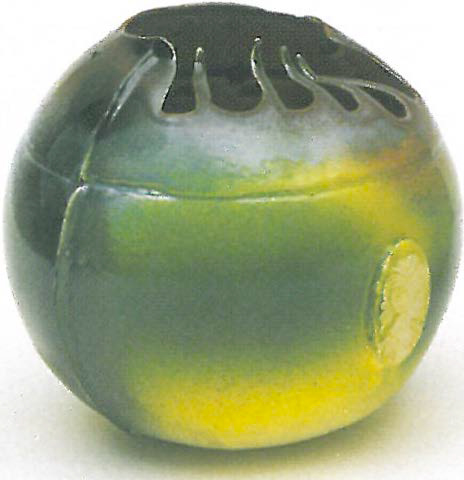

On the other hand, the last artist's etching of twin bush apples (Pinyama), a model of simplicity in design, was punished for no more reason than it had for its main colour an unassuming green that was not quite compatible with the demanding aqua of the wall. While, next to this, Len Maynard's ceramic bowl forms (Ancient Coral) fared well, with their eerily bright glazes. The works, a commemoration of Tasmanian Aboriginal abalone divers, forced to work for colonial sealers, made their point in luminescent style, with a final ironic twist in our discovery of a European cameo brooch embedded into the 'coral'.

Amanda Baxter's more traditional style of acrylic paintings fortunately had just the right colours, and Michelle Brown's predominantly red, stitched textile piece positively glowed. But at the same time it was in danger of being reduced to a mere spot of contrasting red against the dazzling green. In reality, the work has great subtlety in its use of multi-layered colour and symbol.

Possibly, the most striking intervention of all had occurred in the design of the display for the most traditional work in this exhibition. Dulcie Greeno's maireener shell necklaces had, either by the artist's intention or through negotiation between the curator and the gallery, undergone a remarkable transformation.

By this I mean that the change from traditional cultural artefact to stylised contemporary gallery display, should not escape remark. These necklaces are normally circular. Here they were arranged as single strands, attached to foreign gold-coloured metal clasps against a cold circular disc of black perspex – both display support and surrounding brash wall overwhelming their intrinsic delicate beauty.

I left the gallery unable to decide if an act of visual terrorism had been perpetrated. I also could not help but wonder if the works – had they been shown in a sanitised white cube gallery environment – would not have seemed much more than an interesting survey of contemporary practice by indigenous artists rather than the visceral experience it was.