.jpg)

We will examine images of rest, of refuge, of rootedness... The house, the stomach, the cave, for example, carry the same overall theme of the return to the mother. In this realm the unconscious commands, the unconscious directs.

- Gaston Bachelard, 1947

Sally Smart's art practice examines the heimlich and the unheimlich, the canny and the uncanny, houses and blots, furniture and body parts, anamorphic shapes and shadows, psychological spaces as both internal and historical.

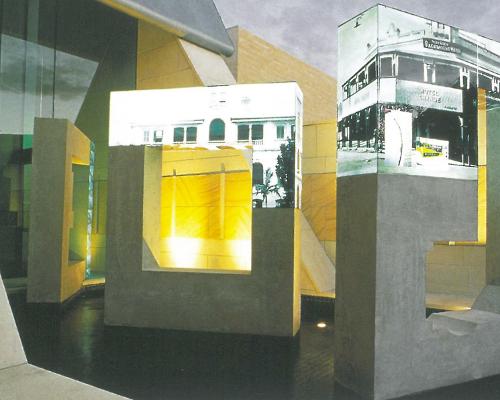

Her latest work, at the Experimental Art Foundation, an outcome of her Ph.D. research, creates a new space within the area of the gallery, an architectural space, an experiential space, and a breathing space. The work, consisting of strips and silhouettes of stiff fabric, old recycled stuff something like leather or interfacing, clads the walls of the gallery like an exoskeleton around the internal volume of the place. This material is not at all precious and there is no hesitation in touching it and feeling its provisional nature. Tough skin-peelings, discarded stuff, flotsam and jetsam. Curiously the cage or skeleton roughly created in a grid over the gallery walls gives a sense of softness to the walls so that it almost seems as if they are breathing or at least bending and pliable. On this net cast on the walls multiple other elements are placed, shapes which suggest movement as well as diagrams and tableaux. A series of cicada-type bugs are pinned around the room and imitate the appearance of the flight of the immense shape-shifting shadow of a fly hurtling around a candle. This familiar experience of flight is however not imitated and the installation thus both refuses and suggests narrative, bringing in pictorial elements and then rejecting their extrapolation.

A tree, heads, a spiral staircase, shells and flowers appear around the walls. A random dreaminess may possess the viewer to make up stories and draw connections between them, are we wandering in a giant subconscious? We may consider echoes of the giant heads of Gilbert and George, the big portrait heads of Mike Parr or the shadow work of Annette Messager or Christian Boltanksi. Within the net, an elaborate series of connections breathe and shudder.

.jpg)

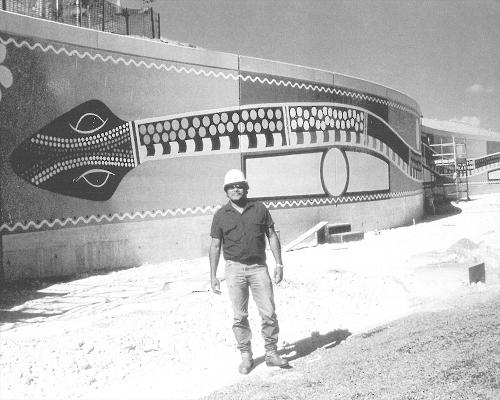

The story of the house that Smart has investigated for this work is quite strange. A La Ronde was built in Exmouth England in the 1790s by two women cousins, the Misses Parminter. The house has sixteen sides with a central octagonal hall. A La Ronde was, for two hundred years, inherited only by unmarried female members of the Parminter family, as stipulated in the cousins' will. An element of Charles Dickens or Edgar Allen Poe walks into the story at this point.

But wait there's more. A La Ronde was intensely hand-decorated by the two women, using shells and feathers applied directly to the wall. Marcus Baumgart, who must have seen the building, tells us in the catalogue that: " Contrary to what one may expect of such types of decoration, the resulting interiors of the house project a striking material presence that is woven onto the fabric of the building, rather than the qualities of an applied ephemeral finish." This, after 200 years, is indeed something. This kind of information makes the visitor crave photographic documentation of the house but what we have is Smart's interpretation - "&in part a psychological portrait of the house, resulting in what the artist herself has termed a kind of 'head-space'."

The work makes you feel something but what exactly is uncertain, breathing walls take us either back to the womb or forward into the somewhat horrific potential future of houses sensitive to our feelings. The free association encouraged by the work comes up on each side against the large black, red or white heads, which watch or surround us like Big Brother. Each contains a map of the Misses Parminter's house, which looks like a diagram of the human brain with rooms for different sections.

The installation envelopes the viewer and, if they have been reading The Architectural Uncanny: essays in the modern unhomely by Anthony Vidler may make them think of the words of Le Corbusier: "A wall is beautiful, not only because of its plastic form, but because of the impression it may evoke. It speaks of comfort, it speaks of refinement; it speaks of power and of brutality; it is forbidding or it is hospitable; - it is mysterious. A wall calls forth emotions."