Thirty years ago, only a generation past, most Australian art institutions collected photographs as documentation, not as objects in their own right. The notion that the act of photographing a person or event was more than mere artisanship was seen as being radical – or alternatively as a bedroom lure of the Playboy kind. How times have changed. At the start of the new millennium photography is not only a major art form, it appears to dominate all other forms of the visual arts. Indeed the most memorable images from the NGA's Federation exhibition currently touring the country, are its photographs – most of the paintings are also rans. Photographs are the images that define our past, our culture and its future.

As with Australia, so with the world. It is now as though everyone sees through the photographer's lens.

World Without End, Judy Annear's exhibition of last century's attachment to the all pervasive medium, is less a survey than a love letter, an exposition of why and how it all means so much to her and to us all.

This is such a huge exhibition that it is almost impossible to define it; to confine it to mere words on a page. There are simply too many works to describe, and too many interlocking relationships between them.

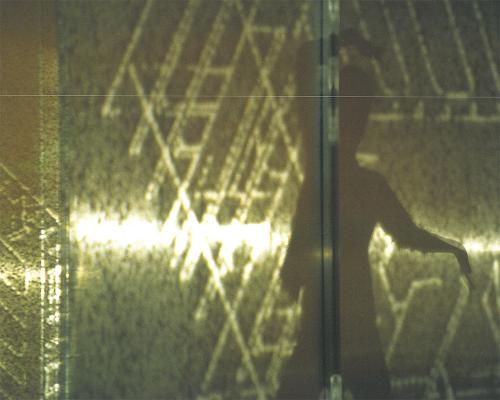

It would be simple to describe the sinister yet elegant ambiguities of Laslo Moholy-Nagy's photograms, of the brilliance of Man Ray's Kiki with African Mask and the way his imagination interlinks with Max Dupain a world far away. Yet these images were all made in the shadow of World War I, that cataclysmic early 20th century event that overlays every idea, every emotion of the generation it damaged. There are overtones of surrealism and also cinema-like theatricality in Frank Hurley's The morning of Passchendaele. The drama is so convincing that the viewer has to be reminded that this supposedly realist photographer used the same tricks of photomontage as the surrealists in order to merge several incomplete negatives to create his theatrical image.

The 20th century was so effectively defined by war that it makes a logical punctuation point in the central court of the gallery. On one side is the staged theatrical drama of Hurley with its triumphalist religious overtones, and on the other Eddie Adams' carefully edited Vietnam Execution, the image that helped turn the tide of public opinion against that particular war. Hurley may have manipulated the details in his photographs, but the editors of the American newspapers who published Adams' photograph selected one image from a rapidly shot reel of film. They chose the image of the moment before the bullet impacted in the man's skull. The photographs of the actual bloody death were too confronting.

The subtext of manipulation is picked up by Yasumasa Morimura in Slaughter Cabinet II. As with all his photographs, he has digitally manipulated a well-known image – in this case Vietnam Execution – and it is his face who plays the executioner and the victim in a postmodernist recreation of the iconic past. In photography nothing is sacred, every object has the potential to be quoted.

The most powerful quotations and modifications of World Without End are not found in the precious studio images, but in many magazines and other pieces of last century's ephemera. These show the effective use of photography in the mass media. In my favourite image – Jack Thompson of 1972 as Titian's Venus – the photographer remains anonymous and only Cleo gets the credit.

As with Vietnam Execution, the other memorable mass media images are composed less as art and more as voyeurism. These are the August 1997 photographs of the late Princess Diana and her lover, reproduced as a prurient spread in the weekly magazine Women's Day which was on sale as the newspapers trumpeted the news of her death. A triumph of the telephoto lens.

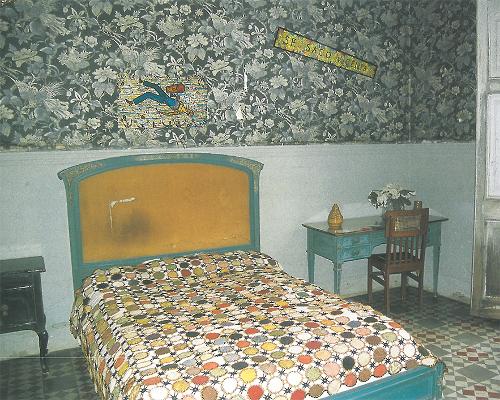

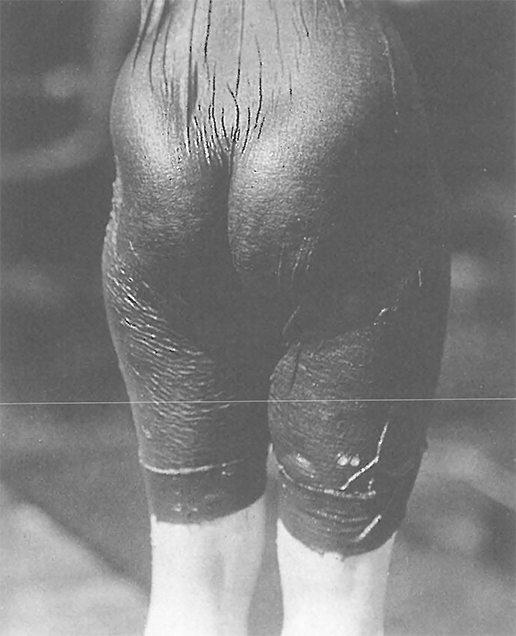

As Annear makes clear in her catalogue essay, most photographs are not the result of intrusion. Instead the photographer relies on the active compliance of the subject. Indeed she goes further, and describes some subjects as collaborators with those who suspend them in time. With some photographers, especially Diane Arbus, there is a sense of interchange as the photographer is privileged to enter the subject's world. But with Alfred Steiglitz it is the photographer's eye that creates reality. Who else would see the poetry of the cloth on the buttocks of Ellen Koeniger, or the disciplined tangle of the poplars by Lake George. Donigan Cumming's Pretty Ribbons series made with Nettie Harris is an even more intimate collaboration, a case of the subject and the photographer working as true partners. In a marked contrast to the airbrushed images of youth that flood the mass media, Cumming recorded four years of the life of her subject as she aged. The poses were joint decisions, as was the exposure of the intimate details of sagging breasts, the crack in her withered bottom, the wrinkled soles of her feet. These studies made with mutual respect make the images of the dead Diana seem even more tawdry.

Not all moments of intimacy are chosen by the subject. The handsome boy in Manuel Alvarez Bravo's The good reputation may have chosen his portrayal, but Alvarez' Striking worker murdered uses a remarkably similar pose to show the ultimate vulnerability of death.

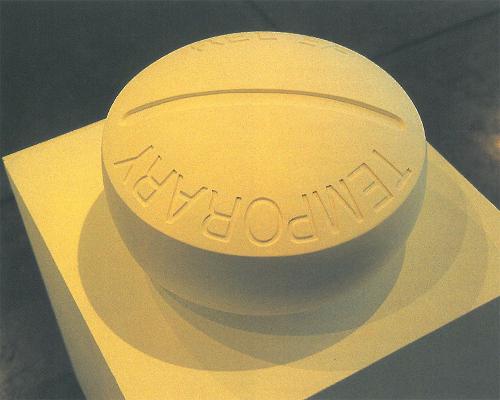

Perhaps the greatest irony of this most simple yet complex of all art forms is that many of these works which were created as a part of the world of mass production should be so physically frail. The light which creates photography can also destroy it. Which is why World Without End will not, cannot, travel beyond its host gallery. Many of the works are too fragile to travel far.

It therefore remains both a definition of one century, placed in one art gallery, tracing the transition from the technology of darkroom and silver nitrate to the digital revolution which already is rendering the notion of unique and rare images into utter meaninglessness.