I was more than a little surprised by the exhibition Modern Australian Women: paintings & prints 1925-1945, not because the work on show is in any way unusual but, on the contrary, because it all seems so familiar. An appealing and accessible show, it necessarily includes works by some of the more well known women artists such as the harbour bridge paintings by Grace Cossington Smith and Grace Crowley, Margaret Preston's colourful and bold prints, still-life and flower paintings, and Thea Proctor's The Rose - works that surely, by now, have become Australian icons.

The show's format contributed to my sense of déja vu, evoking the period of the 1970s when the shift of women's art from museum basements to gallery walls was accompanied by the shock of discovery. During this period of excavation and reclamation the survey style of exhibition was necessary - but is it still relevant a quarter of a century later? Since then women artists have been included in major surveys of Australian art, theme-based shows have been devoted to their work and key artists granted solo or retrospective exhibitions. Women modernists, in particular, have benefited from ongoing critical attention, either as the subject of monographs and/or contextualised within academic investigations of modernity and femininity.

This exhibition with its inclusion of a wide range of artists and art works unified only by gender, begs comparison with the 1975 exhibition Australian Women Artists 1840-1940 curated by Janine Burke. Significantly, the question of relevance finds a response in the quote from Burke that introduces the catalogue essay for Modern Australian Women:

And it is in the wider world I wish to see women artists play their part. For that to continue to happen, we must tell stories, often the same story, over and over, so that it is not lost or forgotten, so that it retains potency, truth and relevance.

- Burke quoted in Hylton, 2000, p. 15

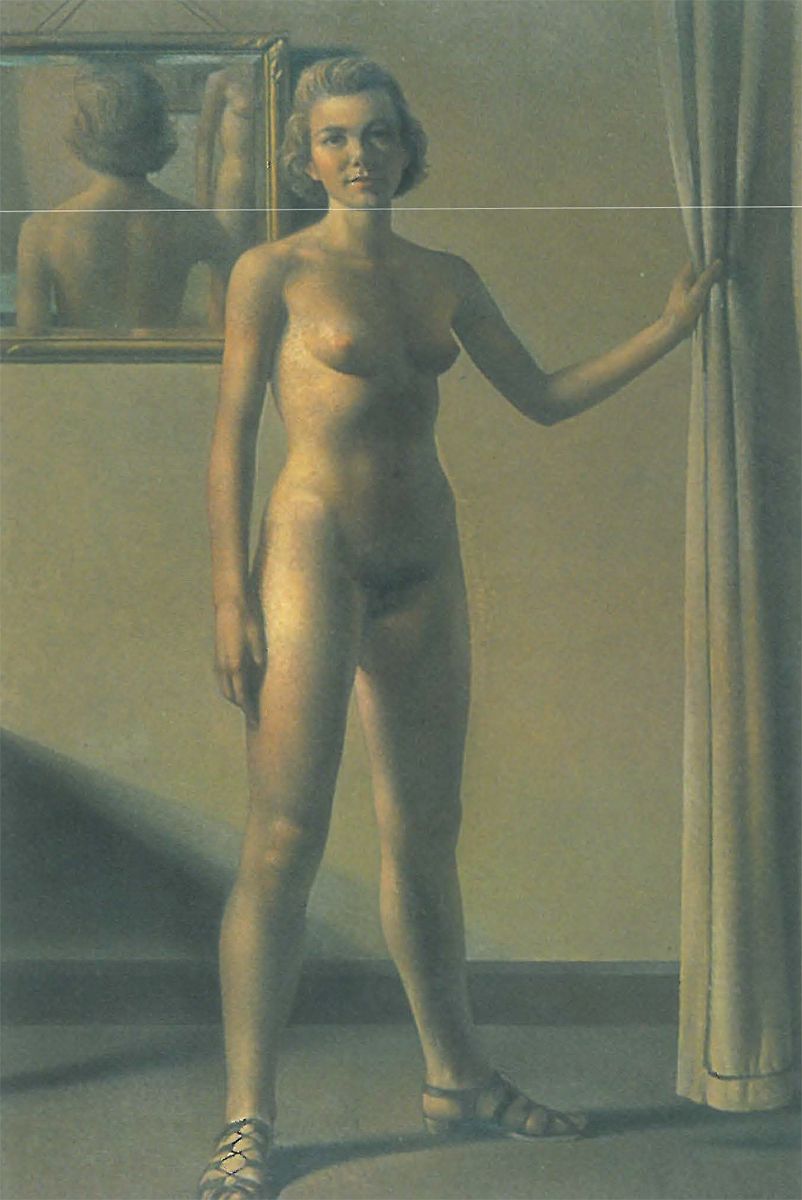

Whether repetition in the form of rediscovery is the best way of overcoming 'forgetfulness' is a moot point, but this is what this exhibition does: it retells the story of Australian women artists for a public that may have forgotten or a new generation that has never known it. There are critical differences, however, in the retelling. For example, the modernist period was represented as the acme of Australian Women Artists whereas Modern Australian Women focuses exclusively on modernism (albeit framed by later and somewhat arbitrary dates) and includes lesser known artists alongside more established names. Australian Women Artists maintained the hierarchy of media by concentrating on paintings. In contrast, Modern Australian Women gives equal place to print-making. This is one of the show's strengths for it recognises the significance of prints as a vehicle for modern ideas. In keeping with the concerns of the time, Burke articulated the notion of a female aesthetic. In contrast, Hylton's show rejects the notion of feminine subject matter or style demonstrating that women artists were just as likely to represent the public space of the city as domestic interiors. Unlike the former exhibition which accepted the established chronology of art history this exhibition can be read as challenging received definitions of modernism for it includes works, which, because of their mimetic emphasis have traditionally been excluded from the category of the modern. The show would have been stronger if it had been less equivocal on this point. Nevertheless, it invites the viewer to consider the essentially transgressive idea that modernism might be as much about new developments in subject matter as about stylistic changes.

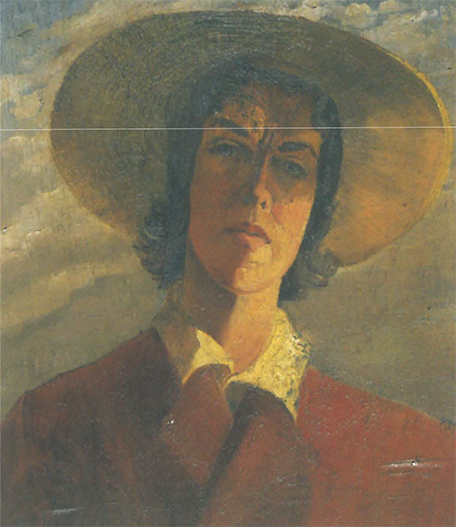

Modern Australian Women announces its interest in contemporary themes with its first two works, Agnes Goodsir's Girl with cigarette (1925) which depicts the modern woman, and Ethel Carrick's On the Verandah (1920s) which represents the notion of modern feminine intimacy. The show concludes less satisfactorily with Joy Hester's Fun fair (1946), a work which clearly has more in common with works belonging to that other exhibition of women's art, In Context: Australian Women Modernists.

In Context continues where Modern Australian Women leaves off. A modest show of relatively unknown works, it concentrates on the period of the 1950s and 1960s. Conventional wisdom has it that after the halcyon days of early modernism women artists disappeared from the scene, pushed back into the domestic sphere by post-war ideology. This show disputes that idea by exhibiting the work of women artists whose careers commenced mid-century. Unlike Modern Australian Women the mood of this show - excluding the exuberant works of Mirka Mora - is comparatively sombre and thoughtful. The work of Jacqueline Hick, Erica McGilchrist and Nancy Borlase (to name just three) exhibits influences from surrealism, expressionism, social realism and abstraction, suggesting that these artists have more in common with their male colleagues (for eg Drysdale, Dobell, Boyd and Perceval) than with the previous generation of women modernists. Far from being preoccupied with family and formica, these artists engaged with social concerns focusing on the representation of marginal and dispossessed groups in society such as refugees, Aboriginals, patients in mental hospitals and anti-war demonstrators. Their subject matter wasn't always bleak, nevertheless, when their gaze turned inward (at the self or the domestic space) it was rarely sentimental or predictable.

The belief that the 50s were far from conducive for women artists has led to the assumption that they were absent from this later phase of modernism. This show demonstrates this to be untrue. Women artists were not playing the role of Brack's vacuous housewife but were actively involved in the developments of the time, looking outwards and casting a critical eye on society.