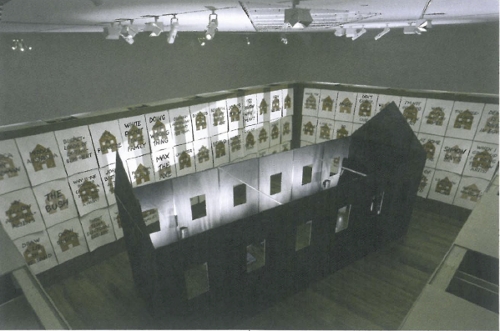

This exhibition, curated by freelancer Vivonne Thwaites over two years, takes a museological approach to its topic by including documentary materials alongside contemporary artworks. Thus wooden-legged glass-topped cases of old publications, objects and photographs are an integral part of the show and the auratic power of the museum, the evocation of the past, is forcefully present.

The slice of Australian history which the exhibition sheds light on is the coming of Christianity to Australia, in particular its encounter through missionaries with Indigenous people. This is a vast task crowded with untold and unexamined stories (not always so much untold as confined to specialist publications) but focused here mostly on South Australia and such legendary sites as Hermannsburg, a name made familiar to many by Albert Namatjira's association with it.

The complexity of events from 1821 to the present, the ambivalence in the relationships between Indigenous people and Christianity - the combination of antagonism and affection, hostility and consideration in these encounters demonstrates a reality which is by no means a clear-cut tale of winners and losers.

The substantial and beautifully designed catalogue includes a valuable background essay by Bill Edwards, a linguistic one by Rob Amery and a contextual one by Marcia Langton. All of them open up the richness of the material to be considered - the writing down of languages in order to make translations of the Bible, the Arnhem Land Adjustment Movement up at Elcho Island when the hidden sacred poles were revealed to assert the strength of Indigenous religion, the language work undertaken by Ted Strehlow, the question of legitimate possession of cultural material, the syncretic figure of Albert Namatjira incorporating and combining one culture with another and so on.

The question of translation, from language to language, religion to religion, culture to culture is an ongoing trope in the exhibition. While Varga Hosseini points out that it is in the very nature of Christianity to believe in translation, as the ability of the word of God to transcend all differences between people is one of its basic tenets, Mary Eagle characterizes translation as something much more fluid and contingent.

Yet for all its historical richness and research, this is ultimately an emotional exhibition, one which seeks, through the investigation of objects, events and accounts of events, to empathise with and draw attention to the suffering of the Indigenous people of Australia as a way of coming to terms with it. Thus its goal is a kind of reconciliation that brings forward the stories and the suffering but also the survival and the respect due to the survivors.

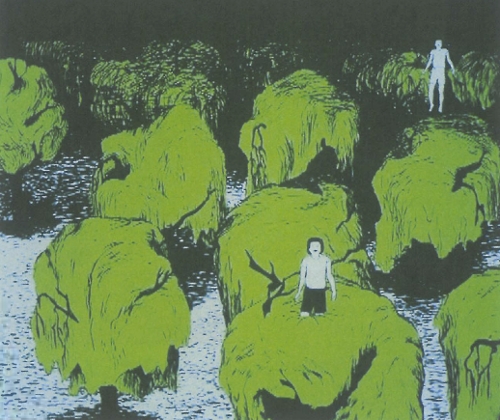

In many ways the work on show emphasises human commonality rather than cultural distinction. Thus the intense sense of the spiritual in such artworks as Long Jack Phillipus Tjakamarra's Tucker Story or Walter Tjampitpinpa's Water Dreaming is also present in Tjangika Wukula (Linda Syddick) Napaltjarri's The Eucharist and Irene Mbitjana Entata's Mission Days/Baptism ceramic vessel.

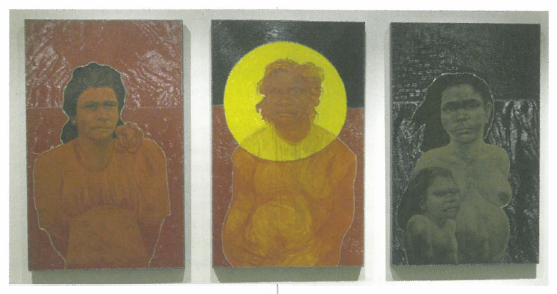

The exhibition is not a simple conventional approach to demonstrate Indigenous spirituality and syncretism, rather it seeks to engage with the complexities of cross-cultural thinking and to this end includes portraits by James Cochran of present-day Aboriginal people, Alan Tucker's history paintings as well as Christine McCormack's somewhat humorous paintings of her collections of Ozzie kitsch. The ongoing force of Christianity in Indigenous lives, whether desired or despised, is seen in artworks by Ian Abdullah, Jarinyanu David Downs, Michael Riley, Julie Dowling, Harry J Wedge, Darren Siwes, Trevor Nichols and Nici Cumpston.

In viewing some of the historical photographs of white garbed Indigenous people gathered around a church I was reminded of historical images of African-Americans and realized that while such images have entered our awareness over many years through films and literature, comparable ones of the lives of Australian Indigenous people are still less known.

This exhibition goes some way towards combating our ignorance and provides us with a strong picture of creativity and vitality, and emphasises that Indigenous people make their own accommodations in coming to terms with a difficult situation.