One of the best things about the Adelaide Festival 2004 was the revival of Artists' Week. While it had its problems it gives the lie to the proposition that in the age of the internet there is no longer a need for people to physically meet to discuss things. The body in the talk is perhaps 50% of the value of what is communicated. Without the nuances of tone, expression and gesture the words become more laboured than they need be in a live situation. Meetings like Artists Week are special because they can afford to welcome people from artists and students to celebrity professors to share the space of an hour (and for the addicts, five days).

Having said that, many were forced to listen to and watch the action on a live video link in a quaint building some 20 metres away, or face half hour queues for the fewer than 200 sardine-like seats in the functions room - all the Art Gallery of SA could supply. The rationale was that Artists Week had been out of commission for a couple of festivals and the tried and tested venue at the Festival Centre would cost and might not be filled. The absence of roving mikes, which have been proved over the past decade to be essential if an audience is to join the conversation, was collateral damage of the awkward set-up.

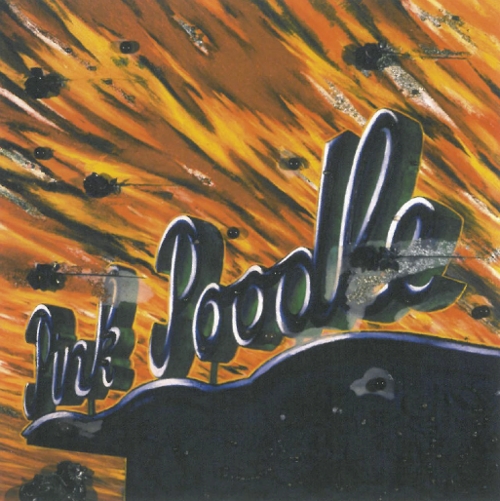

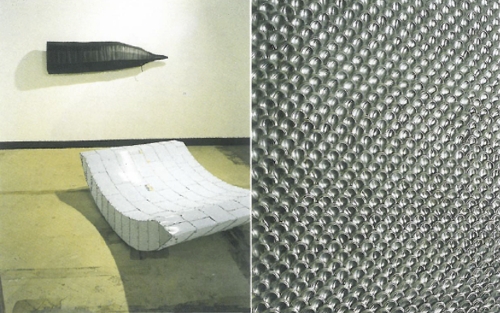

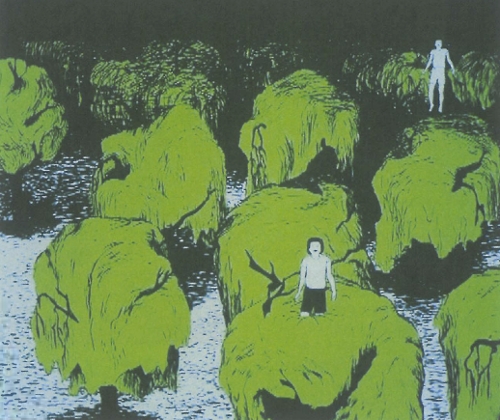

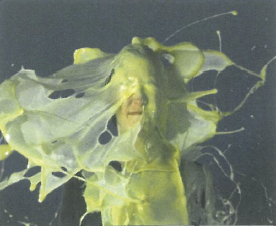

Artists Week started off with a gallery crawl of the Festival exhibitions with artists giving informal talks in each venue. This was very successful, familiarised visitors with the galleries and laid the ground for some of the talks during the week. Some have blamed the 10 am Sunday start for the less than capacity crowd in Elder Hall to hear the celebrity US critic Dave Hickey quietly taking apart the art world. Perhaps news had leaked out. He started by blaming the likes of Matthew Barney and the Chapman brothers together with Tolkien and JK Rowling for a retreat into neo-medievalist violence and grotesquerie. From his vantage point of 50 years as critic he was in a good position to make us laugh, or at least smile guiltily, at things regarded as central to the field, like video art, Biennale Art, plywood installations, gigantic photographs and gallivanting curators. In Hickey's world the art museum industry ('museums are now cineplexes and biennales are tourist destinations') has usurped the role of the patron and because by its nature it is institutionalized it slows down new ideas whereas commercial galleries are the midwives of radical breaks with tradition. It was a commercial gallery that launched Pollock in 1959 and by 1961 had 'made a lot of artists obsolete'. Today this sounds like a looking-glass world ('the Turner Prize is given to those most congenial to the Establishment') and it begs the question of who, these days is The Establishment?

Hickey says the phrase 'non-commercial art' is stupid, either it is good in which the artist gets paid, or it is bad, and bad seems to equate with bad production values. As art approximates to the condition of advertising, film or architecture so its production values increase. His characterisation of video art as forgettable in contrast to a painting which is perpetually renewable, was frustratingly generalised – how much forgettable painting is there in the world. Nevertheless putting the mockers on the serious world of contemporary art from time to time is good if unpalatable medicine and Hickey dished it out brilliantly and with glee.

Anna Somers-Cocks, founder of The Art Newspaper played guerilla fighter to his mercenary. She maintains that 'fine art' is irrelevant to society today and must abandon its current modes in order to work for revolutionary change, it has an absurd emphasis on youth and new invention and has been superseded by documentary video which satisfies a craving for stories. Before she left the editorship of The Art Newspaper she published anti-war statements from prominent artists. However, this was a very surprising speech from someone whose newspaper was founded on the premise of reporting the goings-on of the big museums, the big dealers, the celebrity artists and the world traffic in antiquities. After the two slightly baffling internationals the local content was more predictable. Given the monumental 13 forum sessions running across 5 days interspersed with artist floor talks in the galleries below and sundry keynotes, convenor Erica Green and her co-convenors gathered together a bunch of notables from all disciplines most of whom spoke cogently to the various themes – biotech, war, curatorship, photography, Reconciliation, criticism, architecture, and politics. It is a credit to Green that the week ran smoothly and the vibes were good. More power-packed than most of the sessions was the NAVA day convened by Tamara Winikoff which tackled the thorny issues of Australia's social and political present such as John Howard's famous choice between History and Geography (he chose History). Historian Donald Denoon reminded us about the Pacific, and how in 1883 New Guinea almost became part of Australia and Fiji might have followed but for prevailing racist preferences. And it was artists, he said, who were the unacknowledged legislators of policy, defining White Australia, inventing The Bush and The Beach where real Australians are to be found, ignoring geography. The real job of artists, he said, is to imagine futures.

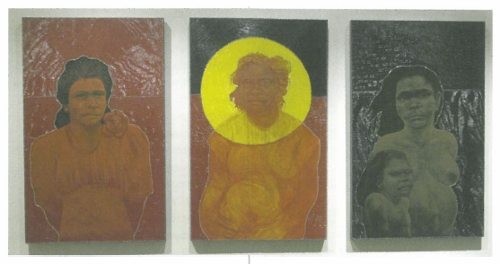

There were more challenges to current orthodoxies in relation to race relations, both recent and in the past. In the critics panel on Monday Susan McCullough talked of the safeness of most writing on Indigenous art and how as a journalist with the Australian she had been attacked for exposing cases of faking. She was taken to task by the measured tones of Djon Mundine who pointed out that fraud needs to be reported to the police, how the sensationalizing of these mostly irrelevant cases had done great damage to an already damaged people. In the Between Land & Language panel Franchesca Cubillo, Director of Tandanya, quietly turned the tables on the politically correct anger directed at the late Elizabeth Durack's invention of an Indigenous alter ego (artist Eddie Burrup) by simply recounting how it was for the Durack family on that remote WA station in the thirties living with Indigenous people. There were moments of mad invention, such as when artist Gay Hawkes modelled a pair of bathers made from the skins of cane toads for the Queen of Making-Do and when the Chaser Team did that rarest of hilarious things – an insider's send-up of the artworld. Burn it to DVD and show it to every art student.

Artists' Week was reassuring in a Festival which was a tad disappointing. For 2006 it needs its own space, more budget for international speakers or artists in residence and a commitment to start the planning now.