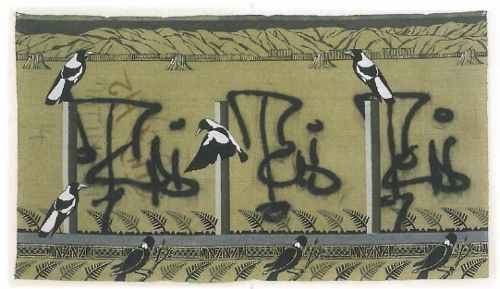

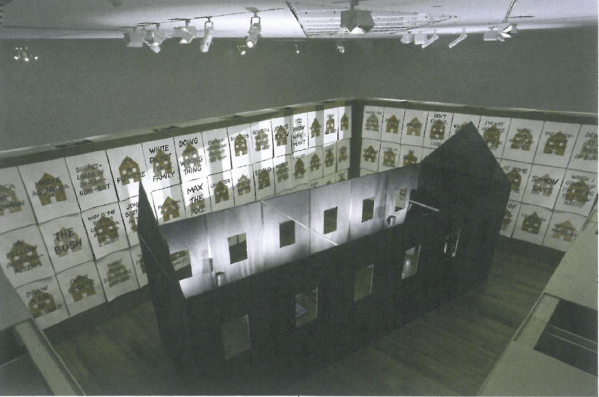

mix), installation view, constructed room, stained plywood building, 258 pencil and ink drawings (overall), lighting on timers, recorded voice (Robby McGregor), sound system, acrylic paint, vinyl text, recorded piano solo of 'Song of Australia' (Bryony Marks). Photo: Predrag Cancar.

When visiting Aleks Danko's installation SONGS OF AUSTRALIA VOLUME 16 SHHH, GO BACK TO SLEEP (an un-Australian dob-in mix), I happened to be looking into the black room at its centre when another visitor's head appeared though an opposite window. As I looked up, a spotlight went on illuminating both of us. We looked stunned faced at each other, framed by black windows and for that moment, we found we had become the centre of a practical joke; a trapped couple staring at each other from the outside of a black box lightly constructed to resemble a house. As we uncomfortably drew a smile in recognition of our folly, the space filled with the velvet voice of television reader Robbie McGregor boldly and brightly articulating a litany of strangely familiar phrase-fragments: 'I'm not going to rule things in or out'; 'A fair go, having a go pulling together'; 'Bucket-loads of ex-ting-uish-ment'; 'Mate'; 'You Know What I Mean'; 'A Long Pattern of Deceit, Evasion and Trickery'; 'Don't Change, Don't Know, Don't Care.' Our gaze broke and we slinked off, hoping never to cross paths again as we explored a boundary wall loaded with scores of poster-sized paintings of little red houses covered with further phrase-fragments.

For the past two years Aleks Danko has been the recipient of the Contempora Fellowship Award, a $100,000 award that attracted much interest when first introduced in 1996 by Victorian Premier and Arts Minister, Jeff Kennett, as a lordly way of rewarding excellence in contemporary Australian Art. Widely critised as a smash, grab and run award, the reinvented Contempora under the Victorian Labor Government requires the artist to partake in a two year 'intellectual residency' at the National Gallery of Victoria, to be actively involved in public programs and to provide an exhibition which tours to regional Victoria. I have no doubt that the hoo haa that accompanied the granting of the 1996 Contempora contributed to the popularisation of installation art in Melbourne. Unfortunately, Danko's current installation has not been widely promoted nor reviewed, perhaps due to the two-year gap between the awarding of the Fellowship and the National Gallery of Victoria exhibition.

SONGS OF AUSTRALIA VOLUME 16 forms the final work in 'Song cycle Volumes 1 – 16' and was conceived as an investigation of Australian culture co-inciding with the instalment of a Federal conservative government in 1996. These years have been marked by significant social and political turbulence embodied by such occurrences as the rise and fall of the One Nation Party, the Wik decision, the Tampa crisis, the GST, the Bali bombing and so forth. It is little wonder that SONGS OF AUSTRALIA VOLUME 16 is a kind of black musical comedy that draws succour from the rhetorical phrases of Australian politicians, the media and common parlance.

As the son of Ukrainian migrants, Danko grew up in Adelaide through the 1950s and 60s acutely aware of issues surrounding the construction of a national identity. As a guitar-playing teenager, Danko developed a strong interest in the ironic and witty use of language. Consistent with early language-based artworks such as Dankorub Portrait, The Danko 1971 Aesthetic Withdrawal Kit and Laughing Wall, SONGS OF AUSTRALIA VOLUME 16 employs language to construct meaning rather than to describe objects. Danko's installation questions the circulation of ideology and hegemony in Australia as manifested through common language. Many of the phrases adorning the walls of the installation mirror the voices of complacency, inertia, bigotry and irony. Take for example the following phrases and see which of the above headings you can place them under: 'Beautiful One Day, Perfect the Next'; 'I Hate To Think'; Ordinary Australians Ordinary Australia'; 'Life (Now) Is Nine Parts Terror And One Part Boredom'.

Danko is no johnny-come-lately to a critique of dominating ideologies. During the 1970s his work was informed by a rebuttal of Greenbergian Formalism, a dogma that dominated art schools and galleries. During the 1980s, he responded to the resurgence of fashionable forces such as taste, distinction and authoritative criticism. Since the 1990s, Danko has tuned his ideology detector to the sounds emanating from the radio of Australian (social and political) Culture. For several decades, Danko has employed the image of a stylised house as an iconic piece of armoury against the conformity of narrow mindedness and complacency in Australian society. The house, of course, can be a place of refuge, of love and sharing. The house, however, can be the Castle that confounds and consolidates, imprisons and snares. Danko's current use of this motif should not be interpreted simply as a bland reference to the small mindedness of the 'Aussie Battler'. This plays straight into any sentimentally charged reference to 'Ordinary Australians'. The motif of the house continues to be powerful as Danko uses it symbolically to represent a mindset. Words which are filtered through the nightly news, the daily paper, magazines, talkback radio, street gossip and the like seem to be the manner in which Danko suggests we construct this mindset.

It is the artist's clever use of symbol, words and spaces that adds strength to his critique of the Australian social, cultural and political environment. Ironically it is also the social and political emphasis that leaves the artist vulnerable. Some critics may raise questions such as, is the artist coming too close to party politics? Australians are uncertain about having their culture criticised. The national myths of sportsmanship, mateship, open mindedness, a fair go and an open and inclusive society are lines that we all continue to spin and swallow. Danko's installation is worth noticing as few contemporary artists hit so directly and hard at these notions of nation.