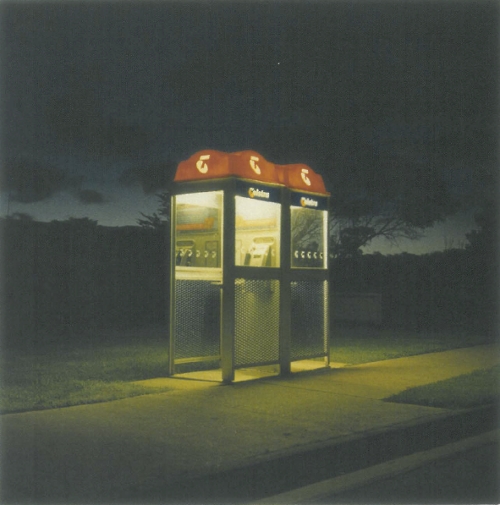

'Step out of the roadworks on shabby Oxford Street and you're in the vast glass hangar of Westfield's new shopping mall, where six floors of retail shops pose as a five-star hotel lobby or a modern art gallery. The art is in the shop windows ...'[1]

So declares a newspaper report on a newly refurbished shopping centre at Bondi Junction, and reference to art in the windows does not mean some artistic project by well-meaning curators to bring art to the masses. The art of the window display here is tied very definitely to commercial rather than artistic brand-names (a distinction, which in any case, is hardly worth making).

The seamless linking of the shopping mall, the hotel lobby and the art gallery, as if no architectural differences any longer exist between these operations, is a register, not only of the all-pervasive reach of commercial culture, but also of the ways in which art is still seen to be a key source of value production.

The cost of this privileged place within commercial space is high – rather like the floor rental cost on the top level of the new Westfield shopping centre, where the biggest names – Versace, Ralph Lauren etc – reside. If it was once the case that the artist embodied true, authentic human production, (after the worker and peasant lost this role with industrialisation) then this cultural mission is simply no longer available.

As Boris Groys argues, the artist today is no longer a producer but a consumer – of the medium in which s/he works – and, as a result, is now part of the logic of general social consumption: 'From being a model producer, the artist has become a model consumer. & The signature of an artist no longer means that he (sic) has produced a specific object, but that he (sic) has made use of this object – and done so in a particularly interesting manner.[2]

It is unnecessary to replay the sad (and false) logic of art's demise in the face of crass commercial culture. One thing at least we know from the history of art is that artists have more or less embraced the market, from the time it became available to them (or they have established alternative markets which have been more or less lucrative for them.)

One thing, however, has changed.

The figure of the artist as radical challenge to mainstream culture persisted for a century or so; it was almost a truism that artists set out to shock the bourgeoisie - and horrified the masses. Now increasingly, it is mass taste (reality TV, pornography, celebrity culture etc) which shocks the artworld and it counters this state of affairs with ever more extreme shock tactics of its own, which are more or less feeble.

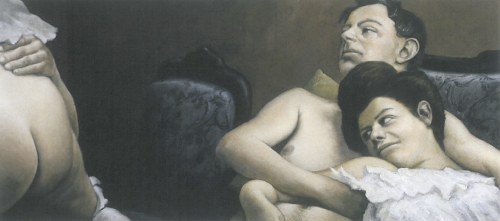

But the game is over, really. Newspaper reviews of art exhibitions have given way to 'food criticism'; nobody cares anymore about the old distinction between pornography and eroticism, which once served to preserve the privilege of artistic expression; now, even artists use pornography, which is firmly established as a popular form. Once the medium of consumption, now money itself is something which people shop for, day trading in stocks and bonds.

And when we begin to look at the history of art and commerce, we have to admit that consumption has been at the heart of this relation – that the expansion of the modern art market coincides with the rise of mass consumption.

This issue of Artlink explores the consumption of pleasure – the pleasure of shopping, of eating, of viewing pornography – the pleasures in general of the arts of life – or 'lifestyle'. Perhaps we can say that this word, 'lifestyle' simply represents the commercialisation of the ethical life within market culture. The market currently promises us everything, in the present (if we have the money), unlike the communist utopia which could only offer future happiness, but there is no reason to expect it will be more successful in guaranteeing what we want than any previous attempts have proven to be.

Consumption too produces its 'backlash'. As the architect Rem Koolhaas has suggested, 'In a world where everything is shopping & and shopping is everything& what is luxury? Total luxury is NOT shopping.[3]

- Helen Grace

'Retail' used to be something you were 'in' and, in an earlier version of the Australian class system, an object of faint ridicule. Now that it has become a vast global juggernaut it invites opposition and protest of all kinds around the world.

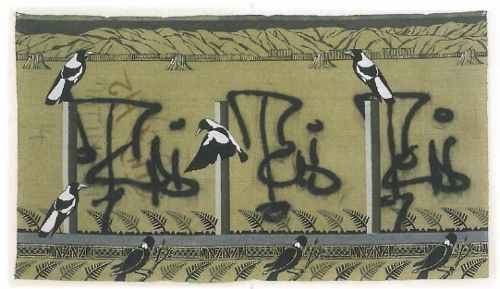

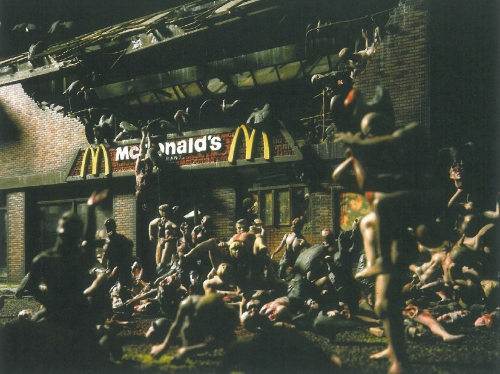

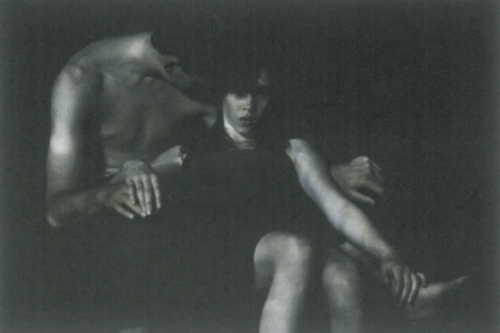

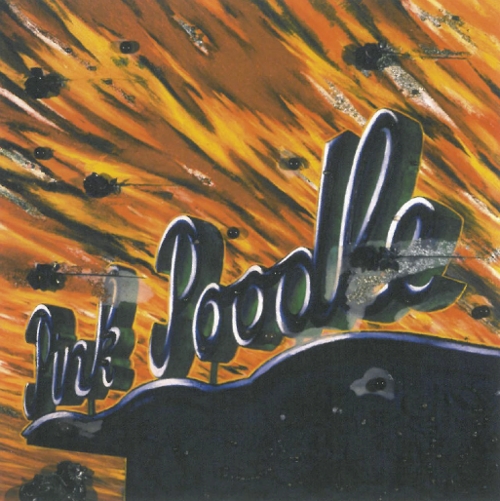

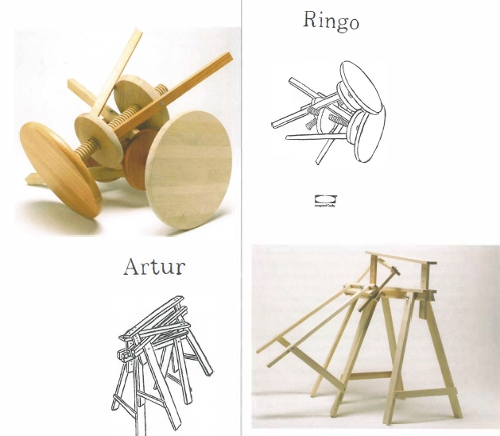

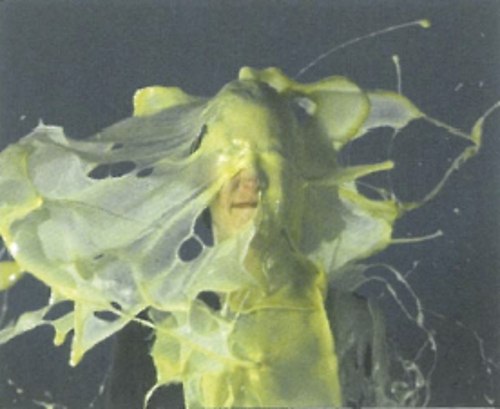

The visible spectrum of retail has a magisterial iconography loosely called brands and artists are among those who reflect on these very blatant codes of persuasion. John Vella, Minaxi May, Marc de Jong. Olga Cironis and Christopher Köller in this issue treat the conventions of marketing and 'product' in ways that are often ambiguous. Some are clearly parodies, others are half in love with the codes and pleasures of shopping. In the area of pornography, an industry of mind-boggling proportions, the art world again both takes the piss (eg the work of Paul Smith) and goes with the flow (eg Bruce LaBruce). In that the human body is shared territory, artists can take advantage of the changes in standards of public decency which porn has helped to effect. The darker work of James Guppy in this issue, with its overtones of sado-masochism, is a complex look at this shift, and takes on extra poignance in a world saturated with the horrifying pictures of Iraqi prisoners at Abu Ghraib prison.

- Stephanie Britton

Footnotes

- ^ Susan Wyndham, 'Credit cards optional, maps a must in th is mall for the brave', Sydney Morning Herald, April 21 st, 2004 p2

- ^ Boris Groys, 'Th e artist as con sumer' in Christoph G run enberg an d Max Hollein, Shopping: A Century of Art and Consumer Culture, Hatje Cantz Publish ers, Ostfildern-Ruit 2002

- ^ Rem Koolhaas, cited in Marx C Taylor, 'Duty Free Shopping' in Christoph Grunenberg an d Max H ollein, Shopping: A Century of Art and Consumer Culture, Hatje Cantz Publishers, Ostfildern-Ruit 2002 p51