Sean Kirby's work has previously prompted writers to prefix their commentary with a statement that he is one of their favourite Adelaide-based artists. I also feel compelled to make such an admission. Kirby was one of the heroes within a core group of artists working in venues like the Experimental Art Foundation and Contemporary Art Centre of South Australia, in the mid-eighties and early nineties. Hewas one of the edgier practitioners dealing with painting, installation and photography, with a grunge aesthetic and a highly complex, conceptual focus. So influential was this group generally, that they could be seen as instigating what has become noted as a typically 'Adelaide' style of contemporary art.

Provisionality was a radical concept dividing the art world between those who found the art 'difficult', and those who got its mix of wry codes. Now we are used to 'difficulty' in art – it has become the dominant institutional aesthetic – do we care much any more? It is interesting to see Kirby's latest work at the CACSA, removed in time from the heyday of Adelaide conceptualism, to ask what it might mean in the context of art practice today. For a new generation readings of established artists' works now combine unarguable feelings of respect and influence, with frustration at the holding pattern Adelaide seems to be operating under. Simple repetition alone could make their works appear formulaic – with a recipe of equal parts Freudian sexual metaphor, architectural references, and abject materiality.

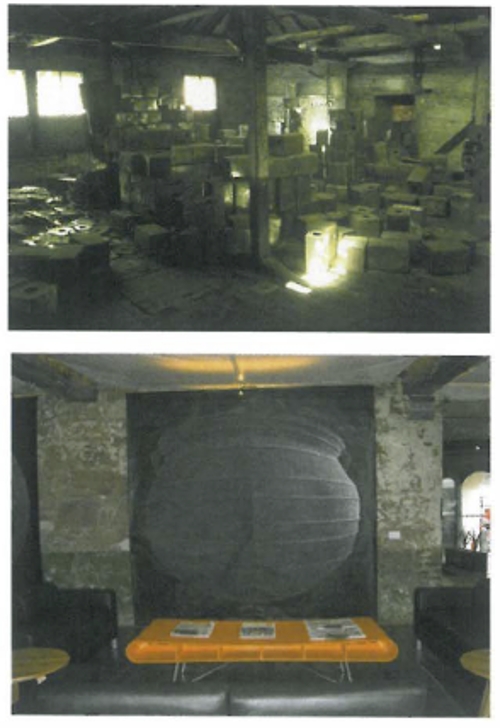

While Kirby seemed to reference many of these fellow artists, his work also rightfully exists outside of any trivial local art-political concerns, and Human Weeds delivered undeniably successful poetic statements, along with evidence of personal artistic development. The rear gallery of the CACSA was most successfully utilised in Human Weeds, with some of the more successful works seen here for some time. This is a space that often seems difficult for artists, or treated as an afterthought; perhaps there the most original and key elements of Kirby's exhibition could be found. Perhaps an emphasis on spectacle rather than abjectness was a partial factor. Most remarkable were a series of vacant photographs of 'tolerance zones' in Holland, out of which grew long, flesh-like pink latex buttresses.

These zones are for institutionalised street prostitution – a particularly pragmatic Netherlands invention. Appearing like sentient plastic excrement, the creepy extensions were a formal element that both successfully described the sucking of life of an alien body probe, and grounded the latent energy and fear generated within the empty photographic images.

In the catalogue the 'Drifter' is identified as a central motif, describing both the artist's own nomadic habits, and also a contemporary and historical figure that society places at its fringes. The Drifter was figuratively activated through a found crocheted toy, walking across a vast mattress-like field. Other vacant architectural photographs could stand in for a perspective of a similarly threatening (or continually excluded) itinerant observer. At the lead up to an Australian federal election (and a return yet again for a deliberately fear-generating government), the images seemed to capture the ghosts of those persecuted under an either/or conception of humanity.

The least hermetic element of the exhibition – a crushed leaf within the hairs of a tacky wig (attached to yet another photograph) – further challenged any exclusivist tendencies, with a sense of empathetic tactility. Nearby, glass bubbles of air activated the forgotten spaces behind a gallery wall - bubbles bursting perhaps, from the spit of hidden mouths.

After moving to Melbourne, and a four-year absence from exhibiting here, Human Weeds firmly re-establishes Kirby's status in Adelaide. It also makes palpable the artistic changes in the town he left behind. Kirby's less qualified, more personal tone felt in sympathy with a general trend to the more emotive work by some of the newer artists working here.

In the Project Space, young talent Emma Northey gave a confident indication of this new direction. A stereo blasted Long Way to the Top, while huge banners of the artist urinating on a cliff top were strung across beams in the space. While reading Kirby's biography, I was struck by the fact that he was able to exhibit consistently in Adelaide's public galleries, in one year (1985) exhibiting at the EAF no less than three times. A very different Adelaide now exists for its equally talented younger artists, with most exhibition opportunities disappearing, or becoming tokenistic. One would expect that they would have to drift a long way for similar support as Kirby's, to develop such a substantial and layered practice as was shown in Human Weeds.