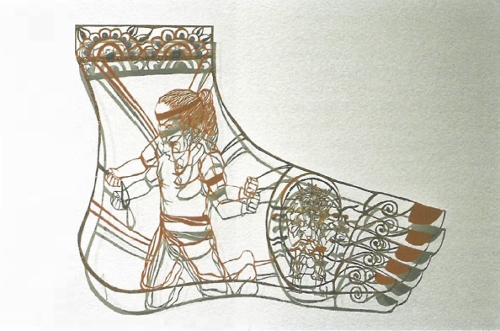

Collage is central to Scott Redford's working methods, but this was the first time an exhibition has been devoted to his compilations of found images. His continuous engagement with popular culture is documented in these works rather like a visual diary. Redford began to receive national recognition in the 1980s with assemblages of found objects bonded together and painted a uniform glossy black. More recently he has been the producer of brightly coloured paintings in the epoxy resins used to make surfboards. He 'produces' these latter works the same way a film producer produces films; the actual making is done by somebody else.

The kind of cool, manufactured detachment reflected in a high-gloss surface seems diametrically opposed to the makeshift look of his roughly handmade collages. While the imagery and components of his paintings and assemblages are embedded and locked in by epoxy, the torn-out magazine pictures could apparently fall off his collages at any moment. Not only do these collages lack the homogenizing effect of a physically binding medium, there is no attempt at unifying pictorial space. Unlike the collages of Max Ernst or James Rosenquist, the figures are not cut out of their original context and recombined into a new narrative space devised by the artist. Instead Redford rips out the whole illustration, often the whole page, and slaps it squarely into the sort of loose grid arrangement we see on notice boards or teenagers' bedroom walls.

The subject-matter, which suggests abiding interests in surfing, trucking, hoon cars, celebrities and naked men, is almost a checklist of homoerotic preoccupations. Curiously, and perhaps incidentally, it also conveys a distinct impression of the Americanisation of global pop culture. Redford includes Australian stars along with the recurring Keanu Reeves, Brad Pitt and Leonardo DiCaprio, but his dedicated readings of high and low American art forms seem the logical destiny of an artist who began his career while a student at the Gold Coast's Miami High.

Sometimes graffiti-like annotations, loose brushwork or aerosol stencilling augment the bits of paper, and there are other found objects such as decal stickers and plastic bags. Everything is applied to a variety of supports including plywood, corrugated cardboard and the interior panel of a car door. The compositions have an on-going appearance, as if things could be added or subtracted. Redford's collages look provisional and temporary.

Temporary, that is, until professionally photographed and seen in a good publication like the one produced for this exhibition by Simon P Wright, curator of the show and director of Griffith Artworks, the publisher of the catalogue. In an extended interview with Wright in the catalogue, Redford observes that viewers tend to prefer the tamed version; 'maybe people just don't want it in the real'. The sure sense of placement and composition that allows his collages to seem spontaneous yet firmly structured becomes much more apparent in reproductions when viewers are not conscious of surface irregularities. And of course art always seems more important when you see it in a book.

Redford's source material is ephemeral by nature, but we think of works of art as permanent. The transformation of magazine clippings from gutter mulch to gallery fodder is a mysterious process that was at the heart of this exhibition. A substantial amount of the material that Redford used for the collages was originally created to feed dreams and fantasies. The pictures come mainly from fan magazines and gay porn. The desire to enjoy their illusory pleasures is essentially a futile one that can never be fulfilled. Redford presents the collages as nothing more than what they are – accumulations of printed ephemera – onto which viewers are obliged to project their own desire for coherence. The works stubbornly resist this. In the flesh, they just don't look permanent or resolved. The fleeting character of youth and beauty, the persistence of mortality, are not simply suggested by the subject matter in the pictures, but embodied in Redford's use of the medium.

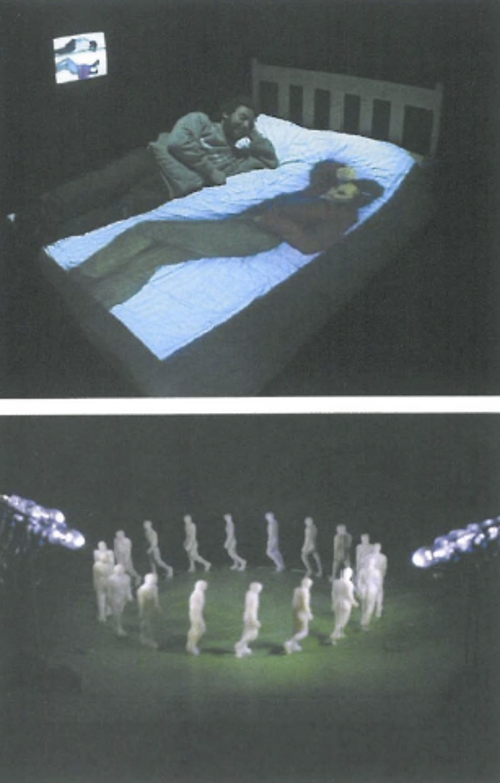

The exhibition also included a DVD of his movie of a movie, the 103-minute Sunset, Then Night, 2004, which from an unchanging camera angle shows My Private Idaho played in its entirety on a TV monitor in a Gold Coast apartment. The apartment is well back from the action and glamour of the beachfront strip, the highrises of which form a thin line on the distant horizon, like the Emerald City, dividing the luminous, slowly changing sky from the drab, unchanging suburban landscape. The legendary skyline is right in the middle of the screen, half way between heaven and earth. The context of a collage exhibition heightened the sense of superimposition in this work; one timescale is layered over another, and hopes and aspirations are superimposed over boredom.