In his recent book Under the Skin Michael Faber creates a race of alternative 'people' – furred, four-legged, with tails and snouts – who perform crude cosmetic surgery so that some of their own may pass as homo sapiens. Though misshapen and scarred, his heroine Isserley still possesses an uncanny eroticism, enabling her to 'harvest' the human males upon whom her race feeds. Mulefa – pachyderms who travel on wheels – likewise offer up an alternative, albeit less predatory, evolutionary outcome for mankind in Phillip Pullman's best-seller, The Amber Spyglass. Both Faber's and Pullman's creations, despite their bestial appearances, are unmistakably, recognisably human, serving to question the very notion of 'humanity'.

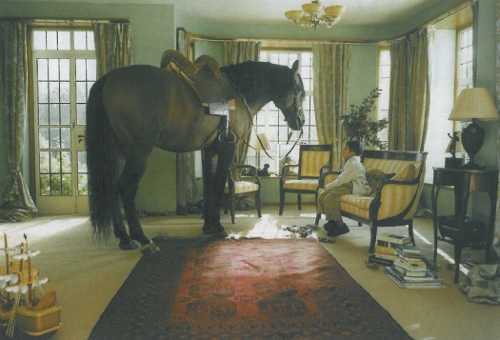

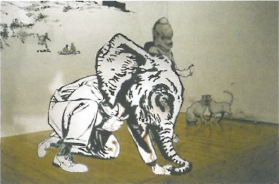

The exhibition Instinct presents a fairly safe selection of 'A list' artists who not only explore the beast as 'other', but also imply that the animal is somehow intrinsic to our identities as human beings. The bulk of the work falls either into the gothic/horror camp - exploring the threatening, the eerie or just plain creepy elements of anthropomorphism - or the abject realm in which the beast represents the ridiculous or pathetic in human nature. The most powerful works draw on anthropomorphism's ability to plumb the primal, totemic significance of animals and their imprint on the human psyche.

Sharon Goodwin's comic book cut-outs might have stepped straight from the pages of Faber's novel. Her life-sized chimeras are the product of brutal surgical grafts, the stitches still raw and bleeding. A bear-faced, deer-bodied beast teeters unnaturally on two hooves, its forelegs awkward and ineffectual. Two decapitated bird heads, one bleeding from the beak, are sewn together at their necks creating a useless, diminished hybrid creature. Only Goodwin's Catwoman with her impressive cleavage and 'Josie and the Pussycat' hipsters seems empowered by her hybrid guise, blood dripping from her lips in the tell-tale sign of a consummate predator. Like Isserley, Goodwin's composite beings are pitiable and repellent, yet somehow accusatory, implicating the viewer in their mutilations and returning to haunt one's conscience.

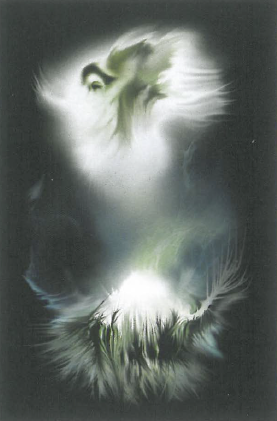

A subtler breed of horror finds its way into the disquieting paintings by Louise Hearman, which seem to exist in a permanent twilight limbo. The head of a Dalmatian atop a pole forms a ghoulish sentry before a suburban house in Untitled #985. A supernatural, perhaps otherworldly, glow hovers on the horizon in Untitled #897, illuminating the benign face of a white cocker spaniel. None of Hearman's dogs are complete; they appear as apparitions, portents, warnings, disappearing into roadside embankments and arctic landscapes, and while the breeds may be modern they nevertheless draw on primeval fears and superstitions. The dramatic lighting amplifies the sense of theatre and highlights Hearman's expert control of mood and paint.

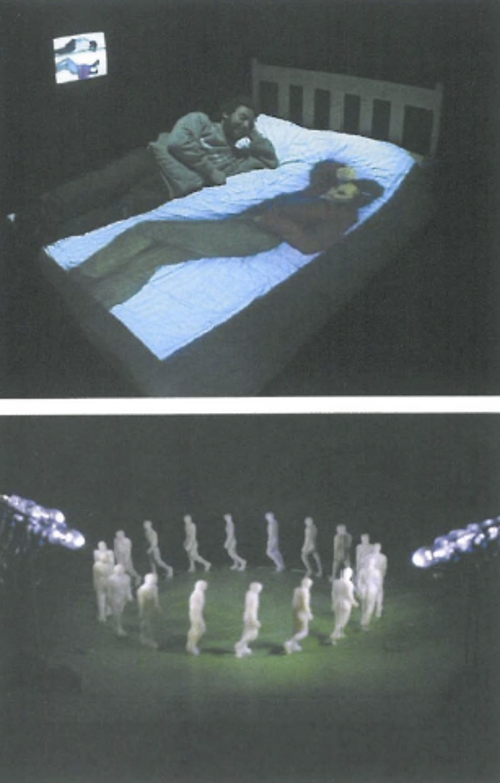

There is a strong video presence in Instinct, featuring in the work of five of the nine artists. While the 'amateur' production qualities employed by Kathy Temin and Ronnie Van Hout are no doubt grounded in sound conceptual frameworks, video pieces that are well crafted and acknowledge the aesthetic potential of cinema (and the attention span of the viewer) are always welcome. David Noonan's beautifully eerie video Owl employs the grainy, high-contrast qualities of early silent horror classics, exploiting the uncanny resemblance of the prosaically titled Grass Owl to our favourite un-dead aristocrat, Dracula. Eyes, black as pitch, stare evenly from the purest of white cowls suggestive of Elizabethan ruffs. Ebony head feathers form naturally immaculate widow's peaks, and even the birds' slow motion, stiff-legged walk echoes that of Hollywood zombies, albeit in elegant stockings. Strangely glamorous, Owl preys on our fascination with the nocturnal, seducing us with the thrill of the chase.

Rebecca Ann Hobbs' thrills are far more innocent. The whimsical Monkey rides transports the viewer back to that first proud moment when the training wheels finally came off. A wind-up monkey, with gangly muppet limbs that barely reach the handlebars, pedals with fixed determination along sun-dappled suburban footpaths, calling to mind the bicycle scene from E.T. It is impossible not to be charmed by this homage to childhood immortality; the safe green lawns ensuring that the final, off-screen crash will result in nothing more than a grazed elbow, despite the absence of a helmet.

While sometimes the works sit awkwardly next to each other, Instinct nevertheless provides a timely survey of the current groundswell of artists exploring not only what it is to be animal, but also what it is to be human.