.jpg)

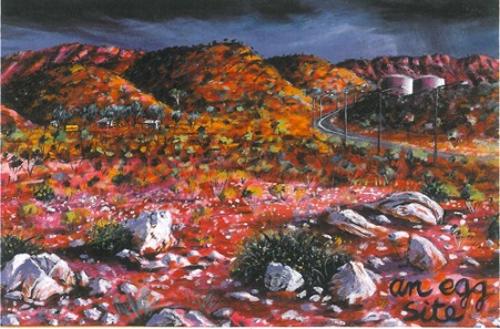

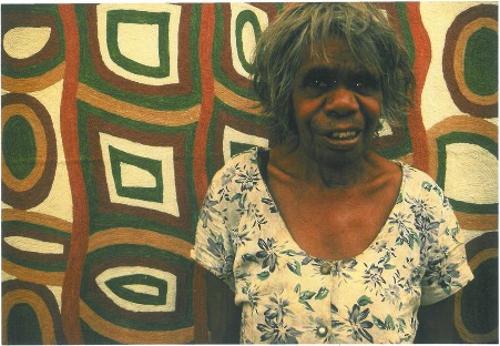

In recent years there seems to have been a growing and unprecedented interest in the art from remote Australia.

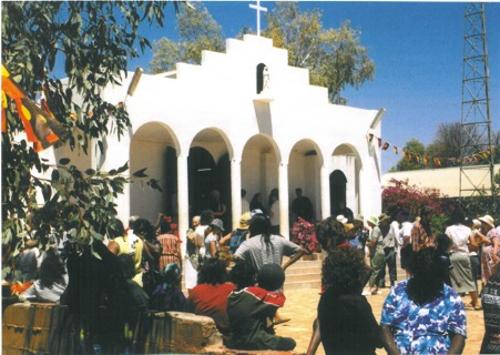

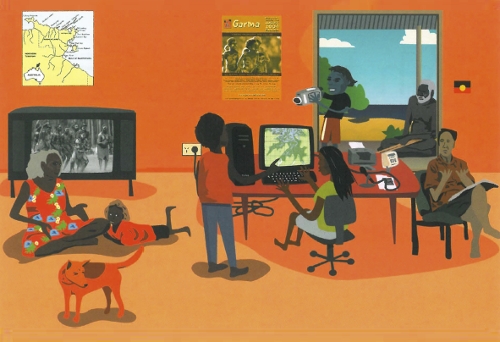

Undoubtedly that has to do with the thriving Indigenous art market and the vitality and innovation of so many Indigenous artists, but it is more that that. There is an amazing amount of artistic and cultural activity going on in some very remote places, not only by Indigenous artists. There are film crews everywhere out in the desert and on the fringes of Arnhem Land, documentary makers and artists doing all sorts of cross-cultural projects, including music recording and the planning of festival events. Increasing numbers of remote Indigenous art centres, as well as non-Indigenous centres in Darwin and Alice Springs, are not only surviving but thriving.

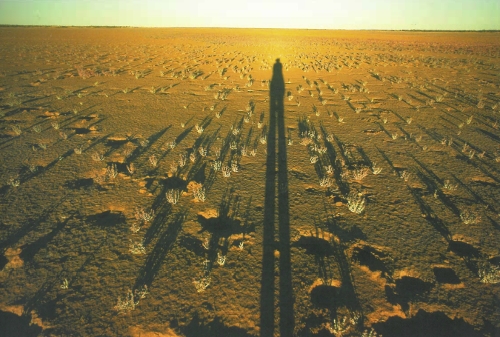

Despite this interest, this is a world that many Australians know little about. The realities and the riches that define living in remote Australia remain distant from most Australians and the national consciousness in general. Caroline Farmer sums up this phenomenon when she notes that coming to the Territory meant “Discovering a world I didn't know existed”.

This issue of Artlink focuses on artists who work in an area loosely called the “Top End”, a geographic construction which does not recognise the border that separates the Kimberley from the NT, moves across to FNQ and also, in this instance, incorporates the “Centre”. Many would argue that neither Darwin nor Alice Springs should be termed “remote'. But most of the defining characteristics, including the complex cultural interface and overwhelming presence of the natural environment, apply as acutely in Darwin and Alice as they do in Maningrida or Mutujulu.

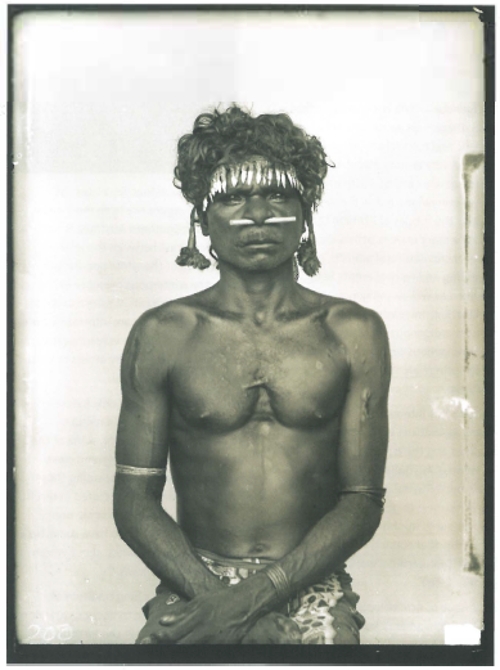

The core issue that separates the Top End experience from most other regions in Southern Australia is the great contrast between the relative transience of the white population with the continuous presence of the original inhabitants. Western and non-Western art modes are informed by these conditions and some very innovative and particular responses by artists of both cultures have emerged.

Therefore Remote not only focuses on Indigenous artists in remote communities but also on some of the more unusual and intriguing cross-cultural encounters (including those with Asia), that have occurred in recent years. It also focuses on some non-Indigenous artists who have spent time in remote communities, about whom less has been written.

There has been a long tradition of exchange between Indigenous and non-Indigenous artists in the Territory. The problematic nature of artistic exchange and collaboration has been widely recognised and debated here, primarily since the ground-breaking Wijay Na conference in 1996 organised by 24HR Art. Marcia Langton, as conference chair, noted at the time that the NT was the critical centre where Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal artists at least speak to each other through their work and should be the centre of a dialogue where some of the silence and confusion about these relationships is addressed. Almost ten years after that intense and at times confronting conference it is interesting to revisit some of these themes and note how the discussion around intercultural exchange has moved on and in some ways opened up.

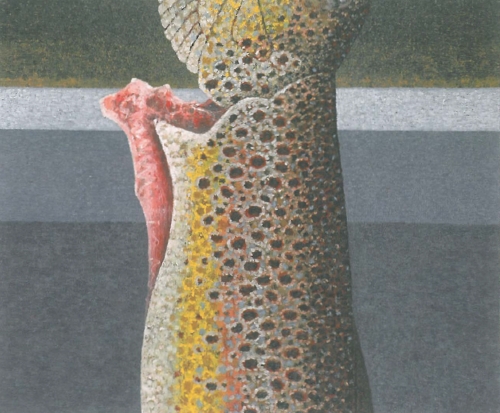

The exchanges written about in this issue are the result of long-term engagements, some of which have led to mutually beneficial creative partnerships between Indigenous and non-Indigenous artists. Some are straightforward and some are more complex and elaborate the highly charged nature of the enterprise of intercultural dialogue and representation.

Like contemporary art in the rest of Australia there is a diversity of themes to be explored. Some “whitefella” artists resist overtly specific references to “where they are” and many remain actively hooked into contemporary art scenes in the rest of Australia and overseas. Others find that time spent in remote Australia is a defining experience that stays with them forever, changes their practice and continually draws them back.

This issue of Artlink has largely focussed on “the intercultural” because it is that which differentiates the remote experience most markedly. Hopefully it may open another window onto this intriguing, complex and lesser known world.