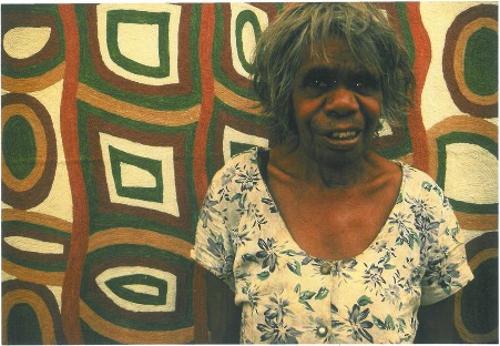

Ngalia elder, Dolly Walker, was born at Skull Creek near Laverton in WA in 1936. Her desert childhood was traditional; she walked the country with her family following ceremony. Her parents, she calls 'proper bushmen' meaning they didn't work on stations. She places herself working on stations at around eight or nine years old and was married to her first husband at thirteen; they had seven children. In 1968, in her early thirties, Dolly Walker began living with her second husband Peter Muir, an Agricultural Protection Board (APB) dogger, with whom she had three children. After a period when both worked as doggers, a job that traversed much of the traditional country of Walker's childhood, Dolly and Peter Muir began prospecting for gold. Success enabled them to 'semi-retire' and pursue other areas of interest, most importantly diverse cultural projects including publications, site protection and painting.

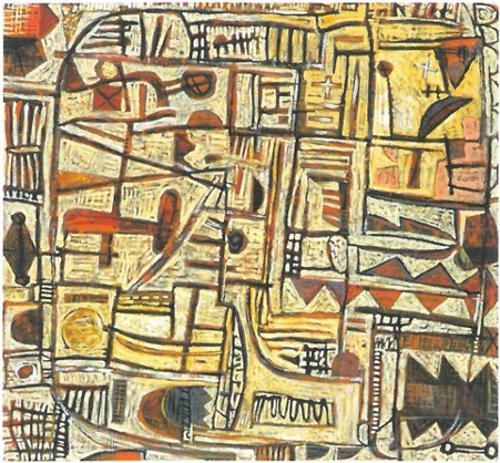

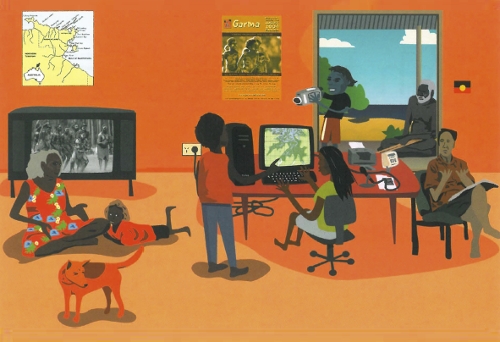

The Custodian, Dolly Walker's exhibition at the Fremantle Arts Centre is an important show built on these strong foundations. There are 36 paintings executed between 1998 and 2004, all of a uniform format, approximately 1m square, and hung three high on the tall Victorian walls of the main gallery. These vibrant pictures are constructed of bright, variegated zones of marks, topographical lines and areas of flat colour. The first impression is of an enormous patchwork. On reading the labels the more decorative aspects of the installation recede and the designs and patterns reveal a deeper substance.

The large number of works in the exhibition tends to highlight the formulaic element in Walker's paintings. Formal designs and sets of patterns are recycled as Walker creates her visual language in the style of a map-maker, employing aggregates of marks and shapes to describe the character of a landscape occupied by stories.

The mapping aspects of traditional Aboriginal art are a commonplace although the ways in which paintings are topographical generally remain obscure to the uninitiated, particularly the viewing public. A classic example is the Tingari ancestors whose secret sacred journeys across the Gibson Desert have been recreated in numberless Pintubi works. The details of these journeys are never disclosed. In marked contrast, Walker's paintings are fully articulated guides to country and story. In fact there is an insistently iconic relationship between the content of the painting and the narrative. This intense focus on story and place is reinforced by the way the paintings are documented on the back with names written against corresponding places. Nothing is left unaccounted for. Some viewers will find Dolly Walker's paintings too prolix despite the motivating passion and innate interest of her survey. These paintings live on the surface; the depth is in the stories. Art collectors tend to want it the other way around. Anyone seeking the visual poetry of a Tommy Watson or a Johnny Warangkula probably will not be satisfied.

The stories have been written up by Dolly Walker's son, Kado Muir. They have a confident rhythm that spares us the awkward expression, riddles and gaps in understanding that are so often evident when whitefellas take down stories. Informal and informative, the narratives crystallise a marvellous span of knowledge, experience and history including what happened in the Dreamtime. The exhibition The Custodian is in effect an exquisitely customised guide to Dolly Walker's country.

Thus far the Goldfields have only thrown up one painter of national prominence, Ngaanyatjatjarra artist Pantjiti Mary Mclean. Even though Western Australia encompasses some of the strongest painting communities in contemporary indigenous art, neither Mclean nor Walker have had the advantages associated with working amongst a community of artists such as exists at Warmun and Balgo. There is not even an indigenous arts centre in Kalgoorlie. This makes Dolly Walker's family-based enterprise at Leonora all the more worthy of our interest and respect. The Custodian would be a wonderful public acquisition in a region parched for cultural stories of this kind. It would also be an inspiration to the numerous other indigenous artists in and around the Goldfields. Dolly Walker has blazed a new trail.