The clear-felling of virgin Tasmanian forest has been a hot source of debate for many years. In recent months, the destruction of the Styx Valley has made international news. Amidst the cacophony of media coverage, local author Richard Flanagan penned an article for the New York Times describing the Valley's battered landscape as reminiscent of 'a World War 1 killing field'.

Poets, writers and artists have publicly decried the actions of big name corporations and one of the most recent examples of creative protest was Richard Wastell's Not far from here, an exhibition dedicated to the Tasmanian landscape (part of a program initiated by the Devonport Regional Gallery to support emerging Tasmanian artists to develop solo shows).

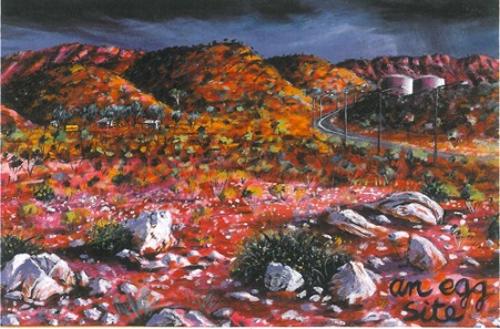

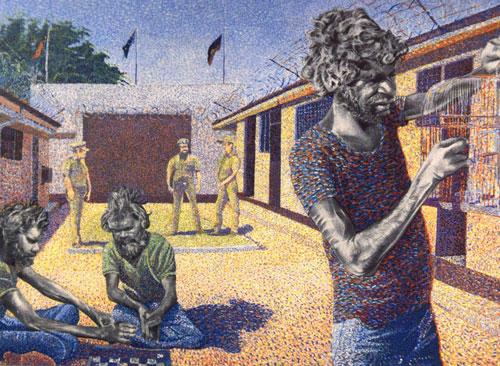

Wastell's work is best viewed in the flesh. Printed reproductions do no justice to his lush surfaces. Through a sensuous mix of oil paint blended with gritty marble dust, the paintings pulse with life as thick sweeps of the brush lick the linen surface in hearty blobs. Void of human presence, Not far from here is an intimate homage to the intricacies of nature and its varied forms of life.

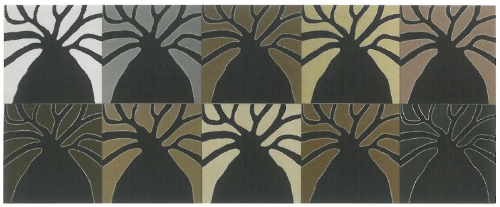

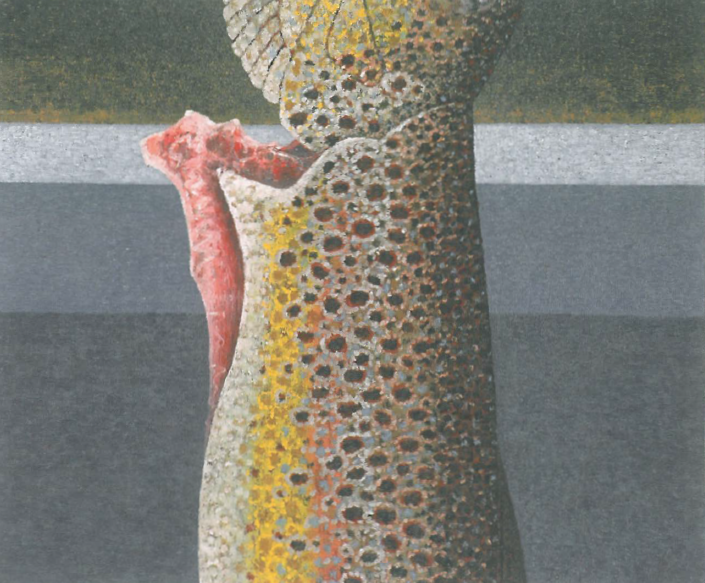

Spending time with Wastell's work clearly reveals he knows his subject well. His landscapes are not the sweeping horizons of fellow Tasmanian painter, Philip Wolfhagen. They are visceral close-ups of organic forms – plump trout, rough torsos of fire-stripped manferns or the choppy water of a mountain stream. In Worlds within worlds and lands encrusted (2005), the sinewy bark of a eucalypt is juxtaposed against an abstracted facade of what appears to be another tree. Thick red strips defiantly crack through the centre of a cell-like pattern of dappled bark. The macrocosm becomes the microcosm as Wastell's vision pierces the surface of nature to unearth the complex rendering of life deep within.

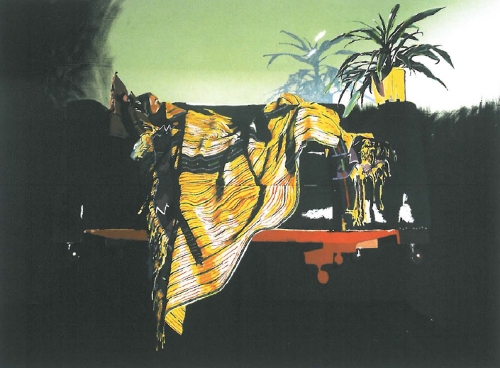

Expert layering of colour, pattern and texture is his greatest achievement. In the title piece, Not far from here. Burnt manferns and firebombed forest, Styx Valley (2005), he has vividly captured the measured crackle of an all-encompassing burn-off slowly festering over the forest floor. Twisted spears of orange paint bleed into a dirty black background choked with marble dust. The intensity of colour and texture emits a visual heat that contrasts with the charred remains of manferns standing desolate in the foreground. One can almost smell the rasping sting of smoke.

Wastell's still life portraits of trout at Woods Lake have become iconic images and are often presented as the signature works of Not far from here. Perhaps less confrontational than decimated forest, works like Good to see you again and Last light, Woods Lake (2005), celebrate the melding of flesh, water and earth. Wastell paints the scaly flesh of fish as though it teems with life; so rich in detail and colour is the depiction. Looking deeper into the work, one realises that beneath the careful mask of colour is the dull tang of death. The prize fish is most likely hanging from a hook while the ghostly grey trees are drowning in dam water beneath a tumultuous sky.

Ultimately, Not far from here is a mournful collection of paintings. Although sensuously composed with mesmerising colour and superb texture, the opulent surfaces ebb away to reveal compositions tinged with sadness. Like the image of a deceased lover repeatedly painted by one still infatuated with memories of a life that once was, Wastell's work is emotionally compelling.

Given the current trend towards digital media, installation and conceptual work, landscape painting is a daring medium to tackle. In Not far from here, Wastell has managed to bring this representational practice to new heights. Coupled with the divine surrounds of the Devonport Regional Gallery (once a gloriously lofty Baptist Church), this is Wastell's best work yet; a marked improvement on earlier, more impressionistic, work.