Melbourne has witnessed several cogent explorations of recent history and contemporary sculpture during the past six months. These in-depth sculptural exhibitions stood up well under the sustained challenge of the 'shock and awe' generated (in a positive manner) by Federation Square and the newly opened Bellini-reworking of the NGV at St Kilda Road. The RMIT gallery's survey of Jomantas and his peers demonstrated the historic importance of the RMIT sculpture studios when the contemporary visual arts including sculpture were consolidating their influence over the construction of public meaning and public values in Australia. Jomantas' work has often appeared clunky, ugly and overrated, although supporting documentation presented an informed understanding of his origins and developments in the context of international modernism. However as a champion and teacher of sculpture Jomantas transcended his artworks and the richness of his influence and support was well proven by an attractive selection of small to medium-scale works from artists as diverse in temperament as Bruce Armstrong and Lenton Parr.

The confident McClelland Award 2003 was a testament to the success of the recent makeover/expansion of the gallery. For a number of decades the McClelland gallery has tenaciously clung to the ambition of taking up the legendary mantle of the Sculpture Triennials in benchmarking and defining Australian sculptural discourse. Now with an expanded and upgraded gallery building and a well-positioned cultural trajectory, it is able to realise that goal, albeit that the price of professionalism and clarity has been a loss of spontaneity. McClelland perhaps has been always a little more classically mainstream and predictable than Heide as a sculptural venue The latter has come closer to engaging a wide audience without compromising professional peer-validation and esteem.

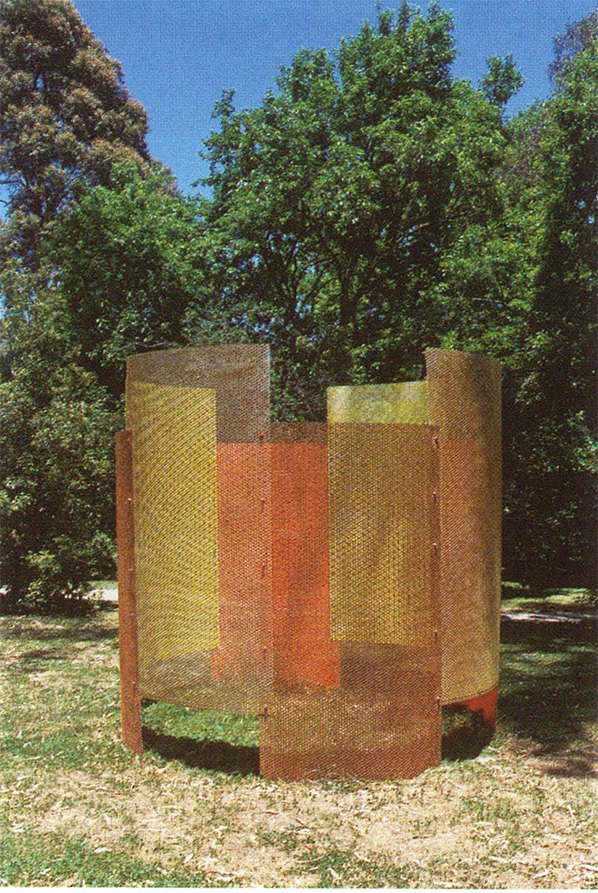

Impressively sited and installed, the outdoor sculpture award confirms the McClelland's vanguard position in any serious discussion of current Australian sculpture. It covered a wide variety of media including sound, glass and inflatable installations, as well as the memorable je ne sais quoi of Peter Corlett's giant Joan Sutherland – literally There is nothin' like a Dame 2003. If she does not come to rest at McClelland she ought to find a worthy home in another public collection. Despite the pluralism of the entries the winning work, John Clark and Ian Burn's Plantation 2003, seemed to affirm the mainstream function and image of sculpture with a monumental wall-like installation. Sadly, in comparison many of the female sculptors' works read as lacks pure and simple without any accompanying Kristevan exegesis. The belle hysterique, eroticism, childbirth and one's own children are a little threadbare as themes after three decades and such works seemed to evaporate under the militarism and power of the winning entry and other large scale metal abstracts. Anna Eggart's freestanding, ghostly metal dresses, Belinda's Wedding 2003, showed that female subjects treated with technical enterprise and fresh vision are viable, mocking the sexist reductionism of avant garde sculptural jocks of the 1960s who dismissed female colleagues and whose spirit sometimes hovers close to any discussion of sculptural values.

Inclusive, imaginative and historically authoritative, the catalogue to Heide's This Was The Future ... will become a standard fixture on undergraduate reading lists. A deft blending of well-chosen works, new and old, with archival photographs captured changing paradigms. The movement from the organic expression of the 1950s – starting with the gifted amateur sculptor Clive Stephen, to the classical cool of abstraction, through new materials in the 1960s including painted surfaces, plastics and perspex, and the irreverent, selfconsciously larrikinesque regionalism of Australian pop and dada was well explicated. The curatorial challenge of capturing the ephemeral and experiential moments of installation art, performance, assemblage, site specific works, the use of natural and environmental materials and the Mildura Sculptural Triennials of the 1970s was met through videos, photographs and support documentation. These images retained an eloquent authority as triggers to the imagination despite their 'after-the-event' format. Bonita Ely's welcome inclusion indicated the input of `70s feminism to expanding sculptural possibilities. Unexpected gems studded the exhibition. Barry Humphries' pisstakes were more compelling than work by his professional peers: Kane, Jomantas and Zikaras. As well as the exuberance of the arrival of colour with paint and perspex, other pleasing surprises were Artlink regular Donald Brook as practitioner, the prophetic qualities of Marleen Creaser's plastic chest of drawers which announced a future three decades of object-based art and Danko and Parks' still funny gaglines.

Since the 1960s Australian sculpture is often dubbed the Cinderella of the arts. A recent incarnation of the metaphor was Brian Kennedy's announcement of the Macquarie Sculpture Prize on the ABC current affairs program PM in November 2000. Imagine my nationalist chagrin to find via an internet search that the Canadians and the Scots have also bemoaned sculpture's secondary status with the same phrase for seventy years or more. Elsewhere art forms other than sculpture are identified as luckless Cinderellas. An Italian website claims that jazz is Cinderella, whereas in Ireland contemporary dance is accorded that title. A Marxist Summer School in Barcelona, July 2001, was told that, come the Revolution, architecture would no longer be Cinderella. Canada goes one better: Jennifer Dickson, Canadian printmaker and photographer, speaking at the 2002 Sweetheart Luncheon of the Council for the Arts in Ottawa, claimed that 'the visual arts are the Cinderella of the arts family'.

Whether this old catchphrase still holds good is thrown into question by these recent exhibitions.