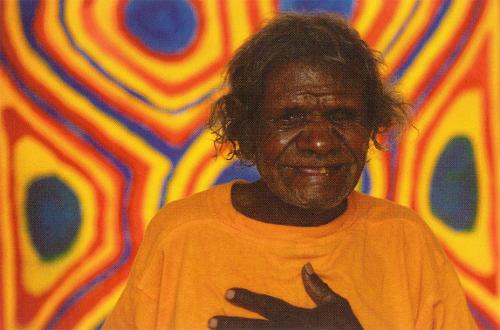

Clinton Nain first came to public attention with his puns on colour and sexuality - White King Bleach versus Black Queens. With the visual savagery of splashes of white paint, bleach and black umbrellas he paraded questions of both racial and sexual stereotyping.

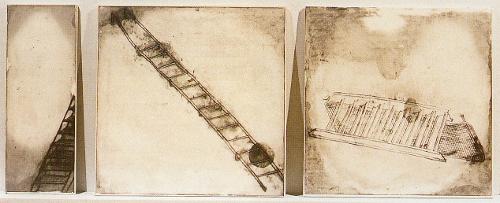

Now, in Living Under the Bridge he turns to the muted tones of Heritage colours. 'Heritage' paint colour charts are used by historically aware home decorators in the sanitised reconstruction of history. Nain deconstructs. Progressive white Australians like to remember the glorious May day when hundreds of thousands marched over the Sydney Harbour Bridge, creating a visual symbol of future racial harmony in a country reconciled. Nain takes us under the bridge, to the dark shadows where the underclass live. This is a bridge that serves both as a shelter, and as a danger - and a reminder that the people who live there are not permitted to walk in the open skies.

There is of course another bridge in the consciousness of Indigenous Australians - the notorious Hindmarsh Island Bridge in South Australia that created a scar, both physical and metaphorical, on our national consciousness.

Nain is the ambassador to those sad ghosts who live under the bridge, who have been conquered and shamed by the conquest of land and water.

He sometimes gives the false impression of being naïve in his art, in those apparently direct puns on Aboriginality and sexuality. In truth Clinton Nain is one of the most complex and visually subtle artists of his generation, and the layers of meaning within his art keep on unfolding.

Living Under the Bridge uses the palette previously seen in his Heritage series. What Nain does to the concept of 'Heritage colours' would not please the marketeers in paint companies. They prefer to encourage home renovators to think of the past in the muted tones of a Federation paintbox. He uses their palette to create a stinging critique of the manufactured past. His house is not a neat inner city semi, but a humpy, painted in heritage hues. Clinton Nain's true colours are dominated by Mission Brown. Its muddy hue can give a breaking heart yet another layer of grief.

Rover Thomas' iconic maps and optimistic roads are subverted into Nain's Big Pot-Holed Road, which ends in a graveyard. The motif of the Christian Cross, used many times in his work, is another double entendre image. The missionaries changed forever the culture of indigenous Australians, X is the mark used by illiterate people to sign their name, and in drawing maps, it serves to mark the spot.

Then there are the targets. They can be simply anonymous, solo or crowded. Either way they seem to take on personalities, with the ultimate goal appearing to be an eye. Then there is the series of dressed targets - Ruby, Mary, Bessie, Polly. These are paintings of shadowy stained shapes overpainted with roughly painted ill-fitting dresses - all in heritage tones. Above them hang the substitute for heads - targets.

The concept of Aboriginal people as targets comes from several accounts of colonising whites using bound captives for shooting practice. More recently, only six months before Nain's exhibition took place, the Queensland Police used life-sized photographs of Aboriginal people (and some white people) as images to be shot in target practice.

There is no refuge under the bridge.