Many people do not possess a penchant for natural history collections of plants and insects, and to some, developing such an interest may seem as likely as discovering an unknown passion for stamp collecting. The contents of such collections are not often described as electric; however in Robyn Stacey's exhibition The Collector's Nature, the specimens that she has chosen are the sources of a glowing light. Stacey has created a series of large-scale colour representations of plants and insects, giving access to specimens previously kept only for the spectacle-covered eyes of scientists.

The photographic montages represent the collections of the Sydney-based Macleay Museum and Herbarium at the Royal Botanic Gardens, as well as the National Herbarium of the Netherlands at Leiden. Focusing on the role of collecting, the works have currency in their sense of place and history with the agenda of building an understanding that collections reflect the habits, thoughts and aspirations of society.

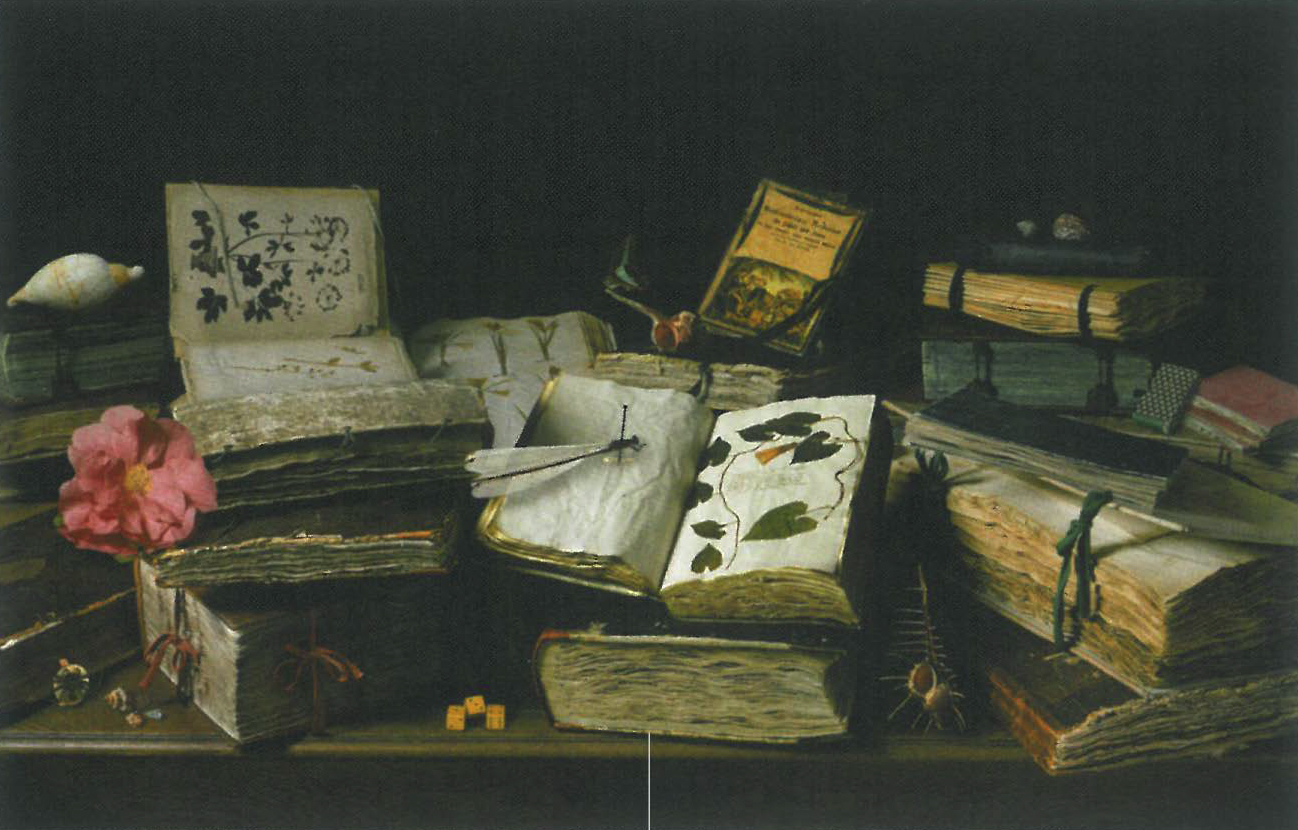

Stacey creates a context in Leidenmaster I and Leidenmaster II through the alignment of objects that possess the same character found in still-life paintings of the Northern Renaissance. As the visiting artist at the University of Leiden in Holland last year, Stacey chose to exploit newly accessible objects and treat them in the same manner as specimens taken from Elizabeth Bay House in Sydney. Stacey mimics Alexander Macleay as the fanatical collector who spent his leisure time importing plants from around the world. Her compositions of old and rare books of botanical illustrations are arranged in an engaging way and hold a series of polite references to the work of Rembrandt. The subject lacks the ability to create a dialogue between the work and viewer with no prior knowledge of the importance of the historical texts. Both images are examples of how too much theory can isolate the image, sabotaging its ability to be read and interpreted outside of set boundaries.

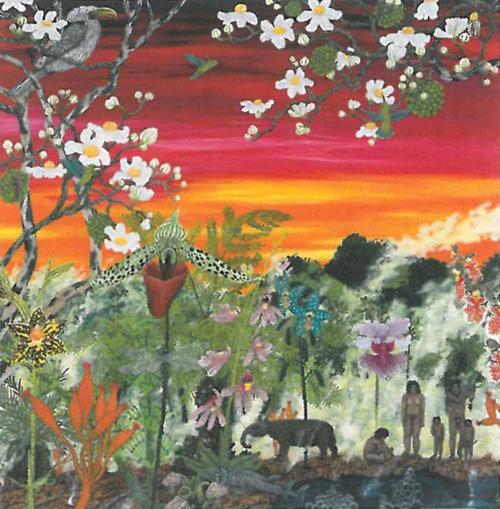

As a whole, the visual quality of Stacey's work is vibrant and energetic. A continual pattern is established through the lingering compositions, with objects suspended above a textureless black surface. Plants, butterflies and shells are magnified, increasing the translucency that is promoted through sublime arrangements. In Fruit and Sky I, a giant pineapple is 'cut and pasted' onto a large clouded sky disturbed by colourful insects absorbing its golden glow. The light that radiates from the pineapple is similar to the illumination of the halo above the head of the iconised Virgin Mary in numerous Renaissance altarpieces, and this treatment raises the pineapple to the same sort of divine status. Stacey has magnified the objects, allowing for a closer examination and appreciation of the unique forms and colours of creatures we often mistakenly assume we are familiar with.

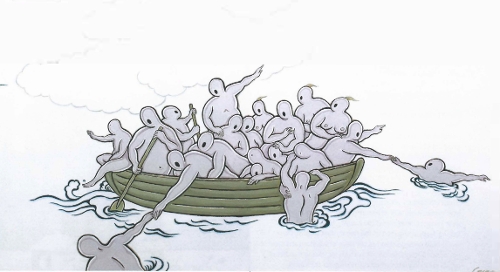

Vortex adopts a composition with a magic-eye quality. Viewing this work might spur an unconscious act of crossing your eyes to see a hidden sailboat, and this is what makes the work fun. Although you won't find a sailboat, you do get the feeling that the images belong on the pages of a twisted fairy tale, a depiction of what actually came out of Pandora's box. All of the images possess the qualities of illustrations, and this relates back to Stacey's own fascination with historical illustrations of botanical specimens.

The fact that Stacey has chosen three separate collections from two different countries does not initially make a great deal of sense. What do plants and insects from a natural history collection in Holland have to do with specimens taken from natural history collections in Sydney, Australia? Is Stacey's choice of sources more to do with her own ability to access the objects than their own value as significant in their own right and when shown alongside one another? This inconsistency of sources does disrupt the theoretical narrative being presented by Stacey; however, this is recovered with further considerations. The historical specimens that she chose from collections in Sydney are not necessarily native to Australia, and it is also possible to consider that the actual objects run second to the theme of collecting. Stacey closely observes the historic link between passionate collecting and the scientific investigation of Australia as a paradise of natural history.

The act of collecting objects from nature is a preoccupation that exists within cultures that are influenced by European approaches to science and history. Natural history collections and the processes that are involved are strikingly similar no matter which hemisphere they are located in, and this is evident through the autonomous characteristics of the specimens used by Stacey. The discrepancy in the origin of the subjects is indicated through the inclusion of certain objects and compositions that are directly relatable to certain times and places. In Eleven Vases I-XI, the plants are mounted in hand drawn vases that are purposefully reminiscent of mid-eighteenth century Dutch paraphernalia in their stylised design, placing the plants in a historical context.

The Collectors Nature is a satisfying series of electrically charged, colourful specimens. The works range from being playful to eerily dark, and such mood changes occur gradually throughout the exhibition. It is the energy of the aesthetic that is successful rather than the heavy-handed theory that is dealt out on the pages of accompanying catalogue notes. Despite the complicated context, Stacey's passion for such specimens has encouraged my curiosity for what is growing at the bottom of the garden.