There is something to be said for those that suffer occasionally from Culturalis Boofheadis. The Archibald Prize? Say what?

What exactly is it about the Archibald that annually stimulates such a frenzied response for what is sadly, a fairly staid affair? It must be something fairly significant to see those who suffer from the aforementioned affliction crawl out from their cultural ruts to attend an exhibition whose history and tradition increasingly says more about it than the content of the show itself. Is it the familiarity? The media onslaught? The knowledge that if you go you will have satisfied your cultural quota for the year, without actually having had to experience anything provocative?

Why is an event such as the Archibald so successful in generating excessive amounts of attention but so lacklustre in producing compelling art? The failure of the Archibald and the institutions generally to capitalise on this attention and to learn from what is being said about the reluctance to embrace anything new and unfamiliar, is something that must be taken on board.

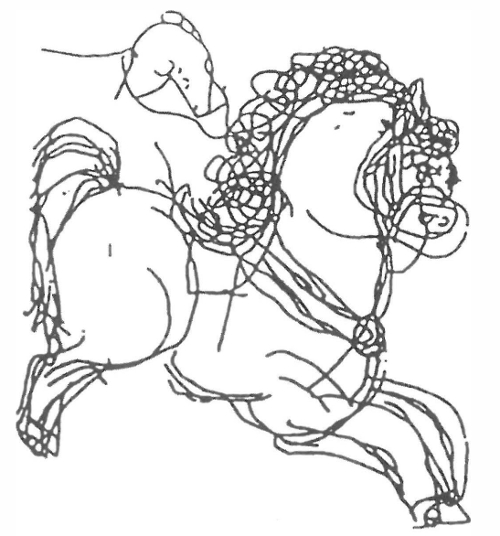

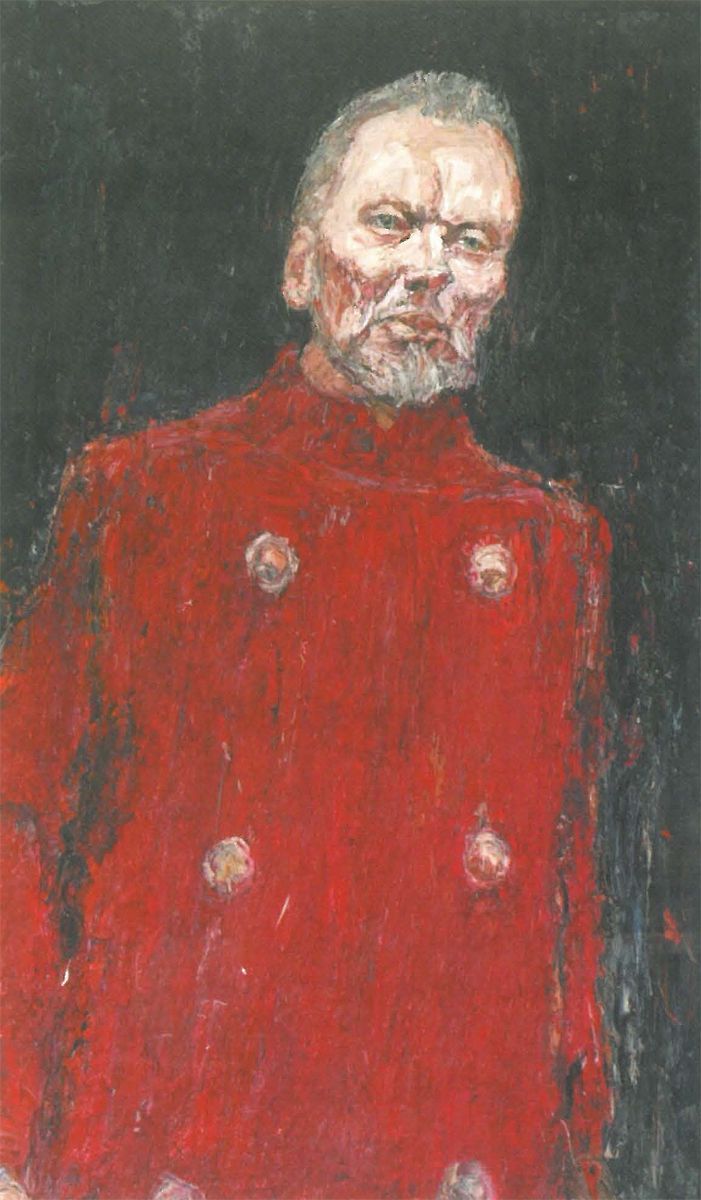

This year's Archibald certainly had some lively and colourful portraits. David Naseby's painting of Max Cullen is an ebullient tribute to his friend and is as engaging as it is aesthetically pleasing, and there are several other works that engender this same sort of familiarity and enthusiasm for example Paul Newton's portrait of Roy and H.G. especially given the recent exposure of his subjects and its selection for the Packer Prize this year. This is certainly not to say that the entrants in this year's Archibald do not warrant critical attention or praise, but it becomes increasingly hard to justify the hoopla when one remembers that the Archibald is ultimately just a portrait prize and despite its history and prestige, a fairly conventional one at that.

The history of the Archibald, and its ongoing popularity are central issues to consider when re-appraising the state of the prize today. When Jules Francois Archibald established his bequest in 1919, it was with the intention of supporting artists, fostering the development of portraiture and ultimately, helping to perpetuate the memory of great Australians. The Archibald still heavily promotes these ideals, even if it is today tempting to question loudly and facetiously the nature of such 'development' in light of the Archibald's recent offerings. Do history and tradition really insist that development be along such conservative and unoriginal lines?

It may be worth looking at the Archibald in much the same way as one examines the fool in a Shakespearean comedy – that unsightly character who mocks the protagonist's folly from the high ground of self-awareness and with a more universal understanding of the world at large, the character who allows for a different manner of thinking, and the one who ultimately has the most fun along the way. Culturalis Boofheadis meet the Bald Archy.

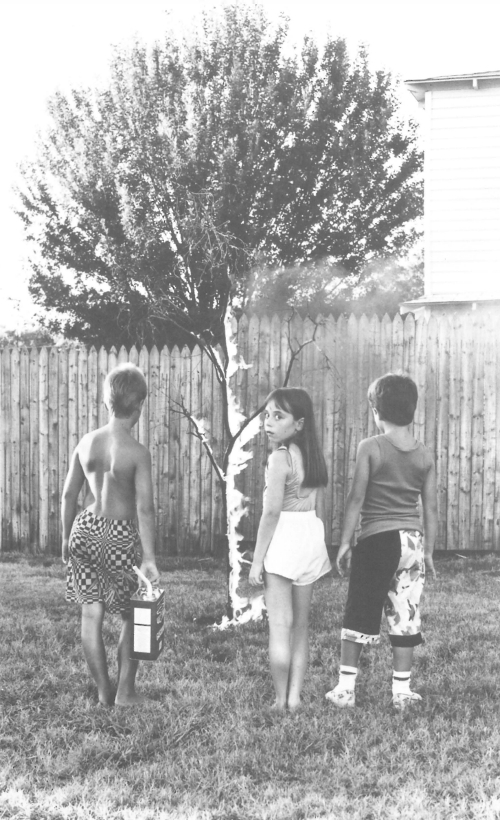

Established in 1994 as part of Peter Batey's Coolac Festival of Fun, the Bald Archy is a tongue-in-cheek take on the Archibald and has become, in its seven years, an event with a cult following all of its own. In much the same way as the Archibald looks primarily to highlight and celebrate the achievements of the artist's subject, the Bald Archy looks to highlight and mock the foibles and follies of its subjects, people in the public eye, once again lampooned for their actions, beliefs and social faux pas, this time under the guise of art. As Batey was quoted recently as saying, the Bald Archy is simply a joke and the moment people start losing that perspective, it all goes haywire.

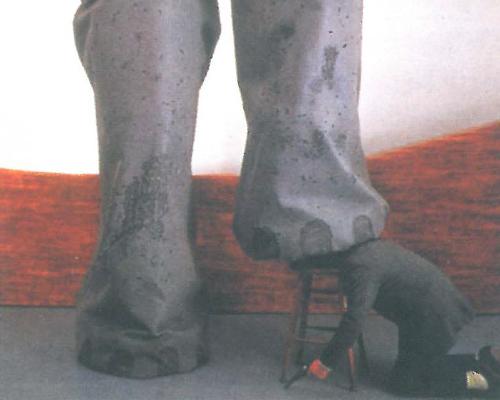

Where the punch line to the joke can actually be found is uncertain but the joie de vivre that emanates from all the works on show makes for an exhibition which is much more fun than the Archibald. This year's winner of the Bald Archy is a true delight – Eric Lobbecke's Skase Chaser is a portrait of Senator Amanda Vanstone, decked out in complete safari ensemble, butterfly net in hand. The same can be said of Vincent de Gouw's Jonathon Shier's Still Life with Shier portrayed sharpening a hapless B2. These portraits are topical, pointed and witty. They provoke a response and stimulate reflection. This is provocation at its best, creating a forum for thought on art and socio-political popular culture.

What events such as the Bald Archy illustrate is that there is an audience out there which is more than willing to look at art from a different, albeit skewed, perspective, that of the irreverent Australian tradition of self-mockery and laconic humour. The Archibald has a clear responsibility to its audience, in the wake of all things Bald Archy, to capitalise on its unique place in the annals of Australian art and its consequent popularity – it must seek for that all-important antidote to the crippling Culturalis Boofheadis.