After four years touring New Zealand, Jenny Harper's visually explosive retrospective of fellow New Zealander Boyd Webb's photographic and performance work arrived in Brisbane. The images in the exhibition fall into three recognisable 'periods' from the 1970s to the mid-90s. Many of them are shot in studio sets using man-made props to represent natural objects. Men, women and plastic animals adopt Monty Pythonesque poses against landscapes of plastic and carpet. The images have a literal quality, where Webb seems to go out of his way to show how they are constructed. Yet, they also pose bafflingly complex oppositions/connections between ideas of language and meaning, object and environment, scale and detail. So, amid feelings of puzzlement and occasionally, repulsion, the photographs' pantomimic quality keeps one laughing (albeit through gritted teeth).

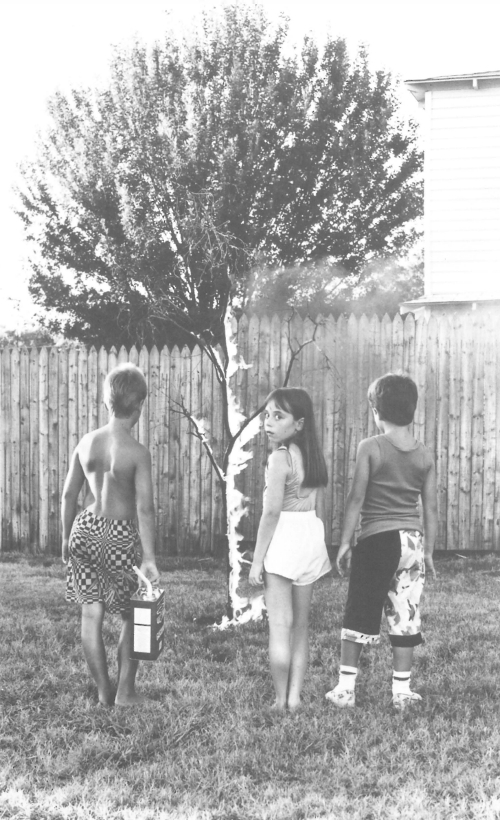

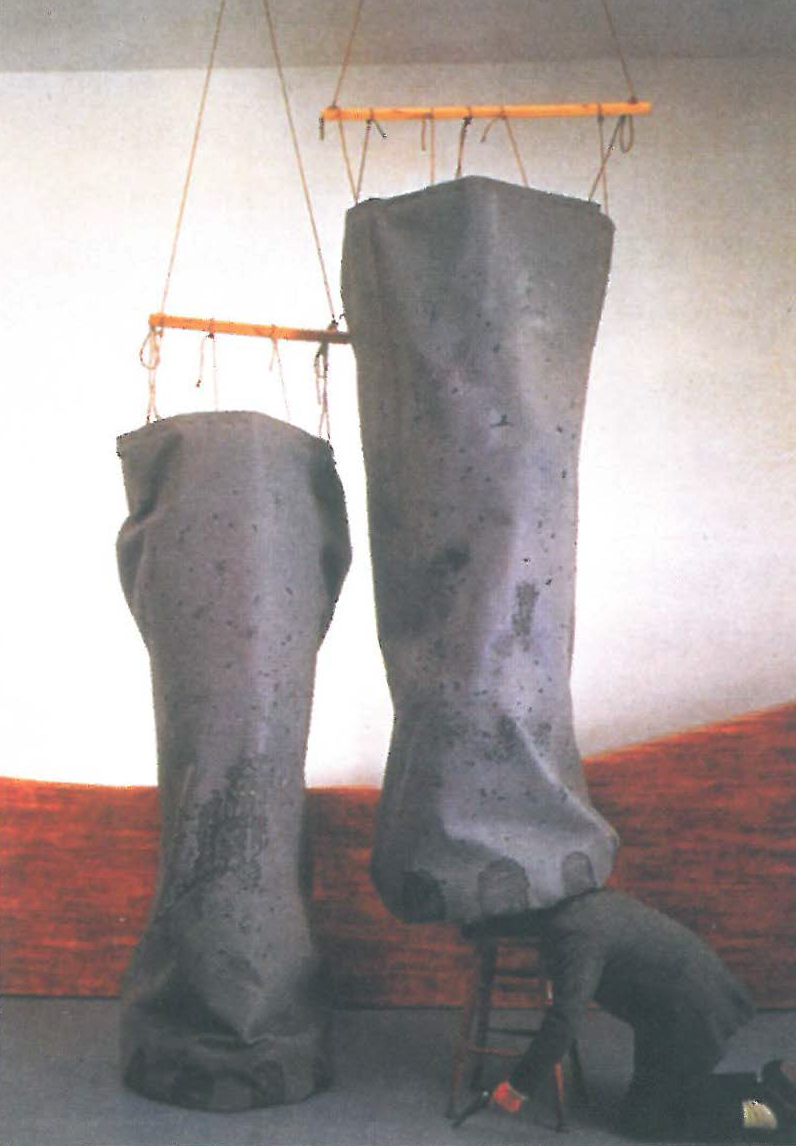

Webb's work often aims to engage the viewer directly, explains Jenny Harper in 'Unruly Truths' in Boyd Webb [exhib. catalogue Auckland Art Gallery, 1997]. While viewing this exhibition, I overheard a man explaining Webb's Negotiant (1982) to his young son. In this image, a man's head is trampled under a pair of rubbery elephant legs suspended from the ceiling by strings (the photograph is almost identical to Webb's 1988 Elephant Legs). The viewer remarked "Perhaps he wanted a different view of the world". At first I thought he referred to Webb's dreamlike, surrealistic view of the world, but when he pointed to the photograph's subject, I realised he meant the man's, not the artist's, bizarre orchestration of 'nature' in order to obtain this alternative view. In all, the comment highlighted one of the 'threads' which links many of the works in the exhibition, albeit tongue-in-cheek, that is, man's understanding/dominance over nature.

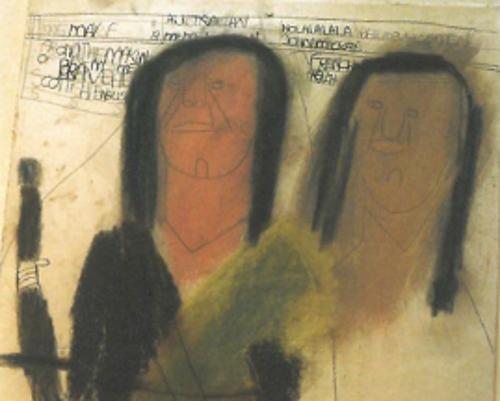

Works like Holothurians (1974) play on man's need to classify and analyse. The work is presented as a one-page script for a videotape. Text is shown alongside image, a signature of Webb's early work. The text describes in intimate detail a scientific analysis of the Holothurian, a mud-eating Sea Cucumber, drawing attention to the act of analysis itself. The viewer is made to question his own analysis of Webb's work, particularly a desire for narrative explanation, which the works often seem to evade. Webb turns our analysis against us, setting us up as his own socio-psychological experiment.

In Mrs Barnes (1976), Webb juxtaposes the scientifically 'provable' with the ambiguity of human behaviour. The second image in the set of two depicts a woman dragging a baby up a hill / saving him from tumbling down& (it is unclear), while a line of text below reads like a scientific equation: "Mrs Barnes' instinctive re-orientation un-equals her desire for self-advancement". The viewer strives to find the narrative, to link text with image to find meaning. Louise Garrett in "The Contrary Vernacular of Boyd Webb", [Art New Zealand, June 1998] notes that the camera has been recognised as that which captures the truth of whatever is placed before it. The historical / ideological notion that the camera revealed objects in their 'natural state' was built around the scientific 'objective' chemical processes of photography, which seemingly rid the technology of its human or 'subjective' association. Webb here turns history on its head to ponder whether the text, as opposed to the photograph, can hold the 'truth' of the situation, and on that cliché of truth existing at all, regardless of medium.

This idea spills into the 1980s works. In the set of photographs from this period Webb extends his use of the studio-based sets, which began in the 70s. In Rudiments (1987) a painted backdrop becomes the cosmos, while a rubbery fabric is the moon's surface. This spatial disjunction between the infinite contained within the studio interior (or the Petrie dish in the 1990s) is seen by Webb as a harmonious relationship: "These two fields are intimately related even though in scale they couldn't be further apart" (see exhibition catalogue). He again embraces the absurd: dinner plate craters hold rotting phallic bananas, indicating a serious poke at man's landing on the moon as perhaps one rooted in male egotism.

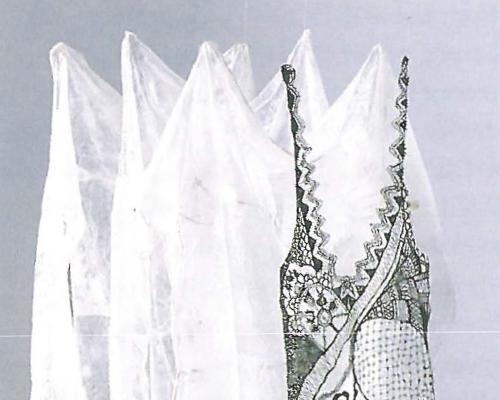

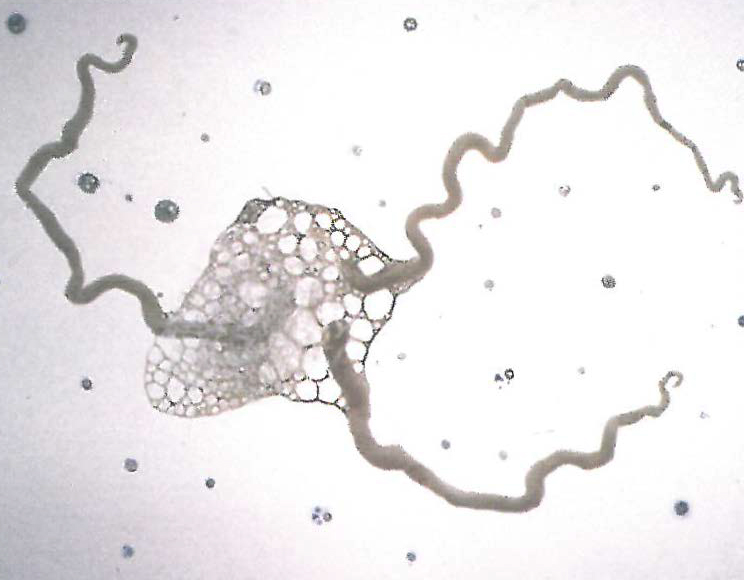

In the 1990s, the 'readability' of the media of earlier works gives way to 'scientific works', where it is often difficult to tell how Webb has shot them. Zygote (1993), for example, features three infinitesimal sperm (whether they are rubber or real is hard to tell), seemingly in the act of reproduction, while works like Vestige (1995) seem to flirt with the idea of digital enhancement in an almost hyperreal expanse of redness. So what of 'truth'? According to Florain Rötzer [in Photography after Photography, Amsterdam: G+ B Arts, 1996] the historical 'truth' of the photographic image has died and the manipulated image (digital or otherwise) holds just as much validity. Webb depicts man's ability to manipulate nature through science, particularly genetic engineering, comparing it with the artist's ability to create new 'truths' through the eye of the camera, a power which he seems to be able to wield over both subject and viewer.