The business of Australia's history has never been so contentious. All of us are these days called upon to negotiate our view of the past in order to obtain a position in the now. It is about identity. About finding a place in ourselves for the sense we make of that which has made us. The self-assured patriotism which secured the Australian population's notions of itself in the first half of the twentieth century is crumbling. Recent decades have unravelled our ability to believe in the nostalgic propositions which have been woven into the Australian Story.

Julie Gough's exhibition Tense Past culminates a decade of work which might be described as an archaeology of nostalgia. Its most striking work - My Tools Today, uses 173 modern kitchen tools to challenge the Social Darwinism inherent in traditional ethnographic descriptions of Tasmanian Aborigines. Such descriptions are frequently perpetuated by the simplistic collections of institutions such as the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery, which is shown, postcard-like, as a huge inkjet printed backdrop. The building is pictured circa 1965, the year of Gough's birth. This work has an immediacy and pertinence constructed around the artist's own identity. But her work resists the temptation of offering unambiguous signifiers of her Aboriginality.

Instead, Gough's work seeks to engage the audience in a dialogue - to transform the viewer into a participant. She continually questions the mode of representations of Otherness which seduces us into a belief that we 'know' Aborigines. As Langton (Well, I Heard it on the Radio and I Saw it on the Television. Australian Film Commission, Sydney, 1993:7) observes:

Australians do not know and relate to Aboriginal people. They relate to the stories told by former colonists& "Aboriginality" therefore, is a field of intersubjectivity in that it is remade over and over again in a process of dialogue, of imagination, of representation and interpretation.

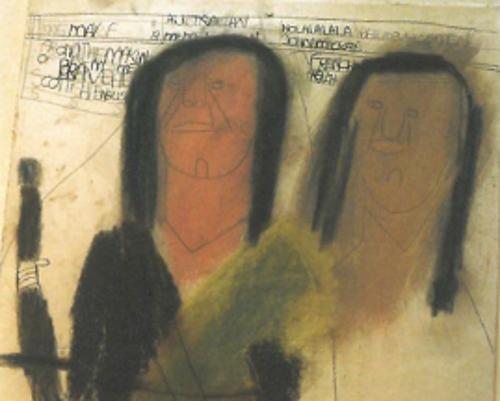

Gough chooses to bracket her own experience and memory within her refiguring of historical narratives, rather than subjectifying herself through stereotypical discourse. Because of an early life in which her indigenous heritage was hidden from her, and her ability to go 'unnoticed in a crowd', Gough has arguably been able to enjoy some degree of 'white privilege'. But if this is true, then it becomes clear from her work that she has been able to use this cover to assume the role of detective, if not double agent.

She has extracted seemingly inane government photographs of Aboriginal children at Luna Park to expose the social manipulation of Stolen Generations in Pedagogical (Inner Soul) Pressure. Likewise, it is the infamy of pastoralism which is invoked in The Trouble with Rolf. Constructed of plaster casts of kitsch Aboriginal faces as musical notation along lines of wire and fence posts, this work was developed from the fourth verse of the well known song Tie me Kangaroo Down Sport by Rolf Harris, the author is called to account for an anecdote of a dying pastoralist who abandons his rights to the indentured labour of his stockmen - with his last words "Let me Abos go loose Lew, let me Abos go loose&" The inferences of power and control are exposed in an otherwise familiar and innocuous piece of Australiana. In Gough's own words:

I believe that the only way to work with imagery, text, inferences that are 'out there' already performing their intended roles in society, is to claim these representations, and reuse them subversively outside their original context. The redirection into new performative roles of their power to damage and undermine can question and redefine our understanding of that past in our country's present and future.

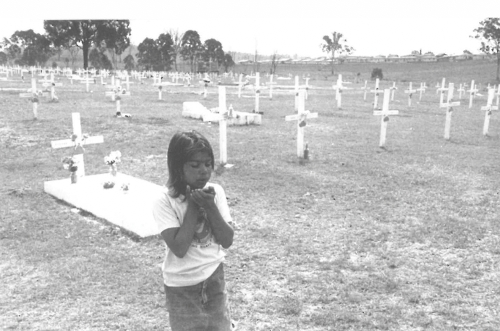

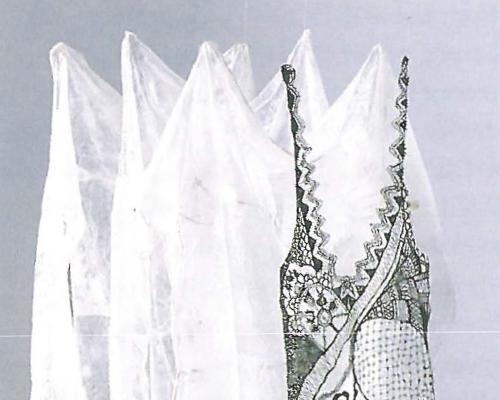

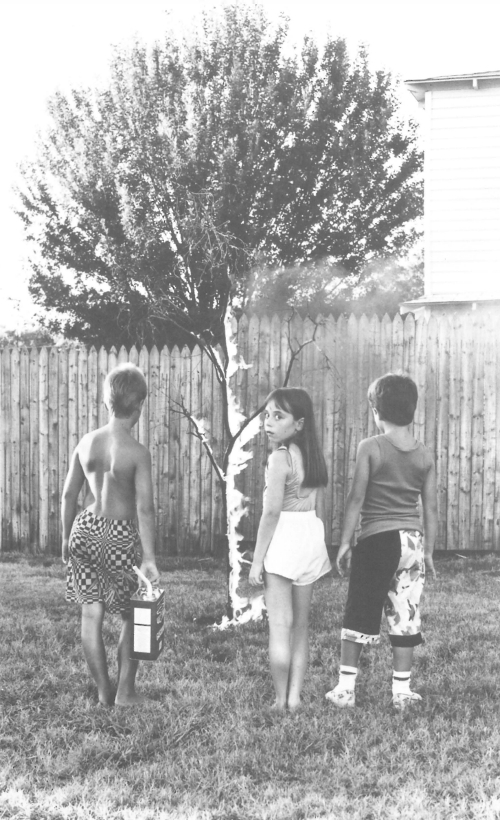

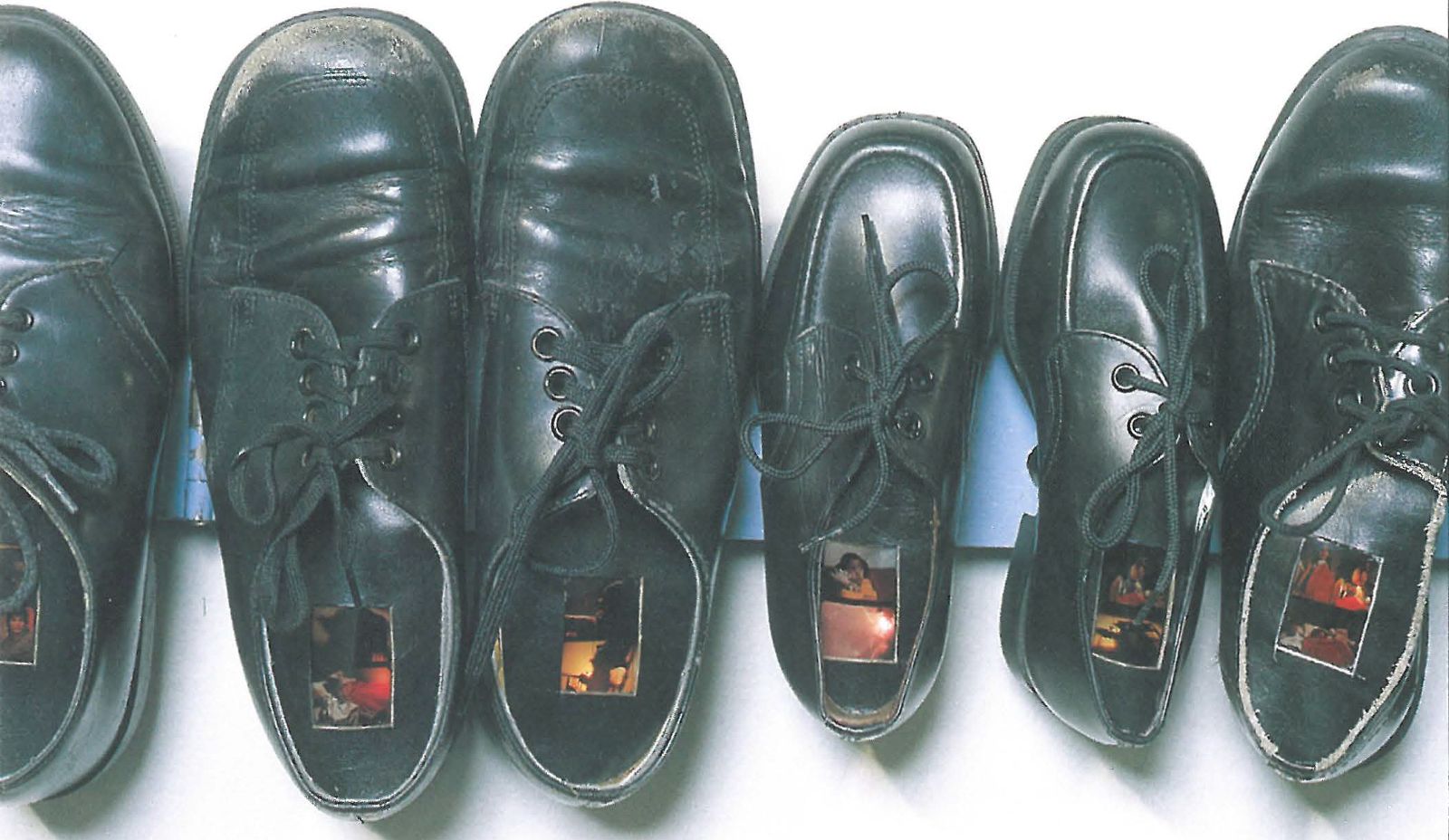

The totalising narratives of history, however, are not the only subject of Gough's inquiry. She also offers intimate and evocative windows into personal memory. Her most recent works included in the show, and how it's been, and rail, are sombre and beautiful memorials to memories to which the artist herself has restricted access. They indicate her own obstacles of encounter with her own past. She describes them as "...free-floating fragments of specific moments and places I cannot quite locate, or hold, or return to."

Whether there is reality in history or memory is not the proposition of Gough's work. It is about the nature of concealment and containment - within the national and the personal. It is about the stories embedded in the gaps of history and the silences of forgetting. It is about the pain of contested identity and the painful beauty of being.