Joanne Saad's photographs might seem an unusual point to begin in discussing an exhibition of contemporary Arabic/Australian art. Images of blond-haired, blue-eyed surfers and car enthusiasts gathering at South Beach in Wollongong, these photographs seem as remote from our idea of the Arabic/Australian experience as can be imagined. But in documenting a self-created and self-defining culture – that of the group that gathers at South Beach – what Saad has done is adroitly comment on the construction of cultures. Less documentary photography, less an interrogation and more an infiltration – Saad has slipped into this South Beach group, itself a marginalised group in Australian society, and through her photography has created a cultural identify and defined its visual coding – the car, the girl, the beach.

Ideas about identity and cultural re/construction inform East of Somewhere. The idea that an identity can be fixed or impenetrable is discarded in favour of a fluid, non-essentialist experience. The curator, Ihab Shalbak, has brought together sixteen artists of Arabic descent (about half are first generation Arabic/Australian, the other second or third generation) who share a commonality in their exploration of the space/s that could be defined as Arabic/Australian. The diversity of the works on display testifies to the diversity of possible positions within this space.

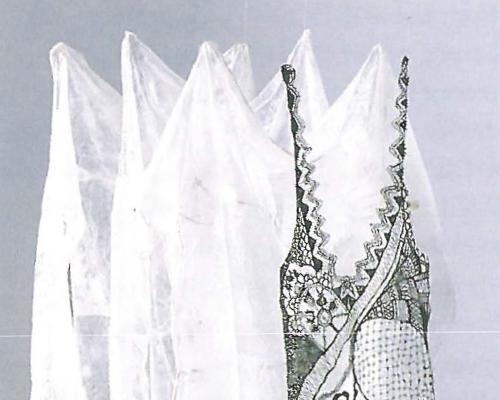

Construction occurs quite literally in the installation work by Fassih Keiso, Curtain for my Window. Having selected images of body parts he disguises them and ornaments them so that they can be reproduced as fabric, furniture, even book covers. These designs ornament the space of a room containing a single bed, large window and study table. The reworked body parts create a certain enveloping pattern and rhythm that refers to traditional Arabic calligraphic art as well as enveloping the viewer.

The physical space is both inhabited by the body as well as the body being absorbed into the physical space. In this way design and the architectural act as signifiers for the experience of the individual as being located in a space and defining a space through their presence.

The traditions of patterning and calligraphy are reflected and reworked in the paintings of Foad Hommadi and the prints of Fatima Killeen. Killeen's print Made Here, Born There speaks directly to the migrant experience reflecting a sense of dislocation. They also act as gifts inscribed to an Australian culture – a new way of messaging and rendering the world. Likewise the paintings of saints and flowers done in a traditional iconographic style by Samih Louka are like gentle offerings to a new home. The work of these three artists is simultaneously transgressive and accepting.

The use of the traditions of text and writing as a way of reasserting a place and identity is also explored in Stephen Copland's painting suite Julia's Diary. Using the diary of his grandmother he explores the migrant experience through reconstructing the texts and reworking, erasing and recreating a heritage. The heavily worked images of flags, tourist scenes and texts speak powerfully of the need to retain the experiences of the past even while they are shifting and changing through the experience of dislocation.

Construction can occur as a consequence of deconstruction or even just plain destruction. Cherine Fahd's photographs The Stone Throwers place the image of young, male Palestinians throwing stones in defiance and despair in a contemporary Australian context. Her Arabic/Australian skater boys in their protective gear holding stones and staring directly into the lens have a bravado that is also full of pathos. The young Palestinian men are maybe not so far from the stone throwers in the Western suburbs who battle their own sense of dislocation –sometimes bridging cultural gaps may only be a stone's throw away.

East of Somewhere navigates a path between some of the possibilities of the Arabic/Australian experience. In refusing to settle on a particular code or motif, the exhibition as a whole makes clear that identity can move and shift, can be dislocated and reconstructed. From the marginalised experience of the migrant can come a narrative that both acts as de/centering as well as adding richness to and subtly subverting the dominant culture. Douha Baroudi's photographic work perhaps best captures this idea – three Arabic/Australian women meet for morning tea, a traditional way of socialising for Lebanese Australians and a way to overcome isolation. The photo's title – Australian Landscape.