It's nice to see a bone being thrown to contemporary artists again, especially after the demise of big awards like the Moët et Chandon and Contempora 5. It's the sculptors who are making out this time around – firstly in this, the Helen Lempriere National Sculpture Award, and later this year in a new contemporary sculpture prize at the National Gallery of Australia.

With a first prize package of over $100,000, the Lempriere looks like a pretty meaty bone. It's surprising then that the list of finalists doesn't read more like a who's who. In fact, the finalists' biographies reveal that a surprising number, despite having careers spanning decades, have had little in the way of those things we usually measure art world success by – shows in the more prestigious contemporary art spaces, for example, or published critical discourse about their work.

In a way, I suppose, this should be refreshing, an indication that the work was judged on something other than the artists' reputations. Indeed, in an ABC-screened mini-documentary on the award, judging panellist Elizabeth Ann Macgregor mentioned that the works were judged initially on the concepts submitted in the artists' applications. This revelation incidentally, leaves one wondering just how self-conscious or ill-considered the artist statements that were rejected must have been. Of those that made it, groan-inducing proclamations that their work makes an "ironic statement" for example, should have been enough to sound alarm-bells.

For the most part, though, whatever the selection process, this exhibition of finalists amounts to a strong and varied show. The best works manage to combine something of the characteristic immediacy of monumental sculpture with wit and beauty, or layers of references and potential meanings to maintain our interest.

Stephen Birch's beautifully constructed Untitled does just that. A spear-like fibreglass tree trunk which knots upon itself toward its top, Birch's simple work is an inspired and perfectly realised mix of dopey humour and elegance. With more humour, and a slacker aesthetic, Claire Healy's Formica Tower, a retro caravan encased within a tower of scaffolding, pokes fun at the reverence of the formal gardens, while suggesting its own aspiration to monumentality.

Of the many formalist and organic abstractions, Simeon Nelson's Pollinator Phenotype (Cactal) and Dani Marti's carpets of red and yellow scouring pads, Blue Angels, are notable, sharing an insidious appearance of potential auto-generativity, and a bizarre conflation of the natural and synthetic. So too the lurid purple fake boulders of Deej Fabyc's Gateway to Mag Mell 2001. Fabyc's fantastical polyurethane dolmen is overwhelming and evocative, alluding both to ancient monuments and theme-park disposability.

Along the same lines, and equally theatrical, Mathieu Gallois' Drive Thru–an astonishingly detailed life-size replica of a generic fast-food restaurant–is, though, genuinely ephemeral. Rendered in dazzlingly white polystyrene, the stunning blankness of Drive Thru is suggestive of utopian dreams and consumerist nightmares.

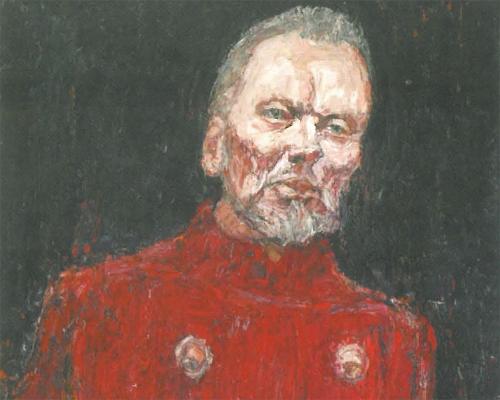

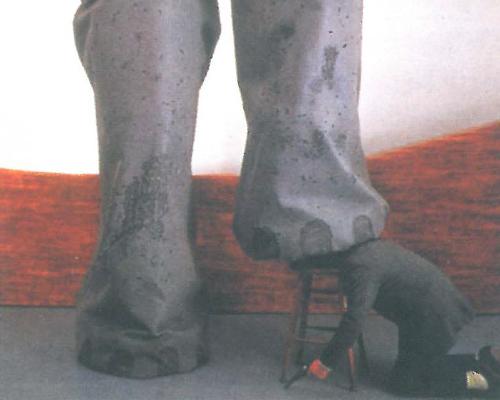

Kristian Burford's Robert has also lost interest in his garden, is comparatively more guarded in its complexity. The hyperreal figure of Robert lying naked and prone in his neglected glasshouse is surprising and enigmatic, the engagingly multilayered tableux earning Burford (along with Gallois and Birch) the judges' commendations.

The prize, though, went to Karen Ward's stylised cubby-house, a steel-framed plywood construction, Hut. Certainly it seems the judges were impressed by Ward's patter, repeating her line about Hut's inaccesibility (sure, there's no door, but it seems no-one noticed it's quite accessible from underneath). It's likely though, and perhaps a lesson for future entrants, that Ward's win had more to do with a successful straddling of formal and conceptual concerns – thus appealing, in part, to all the judges – than her ability simply to talk the talk.