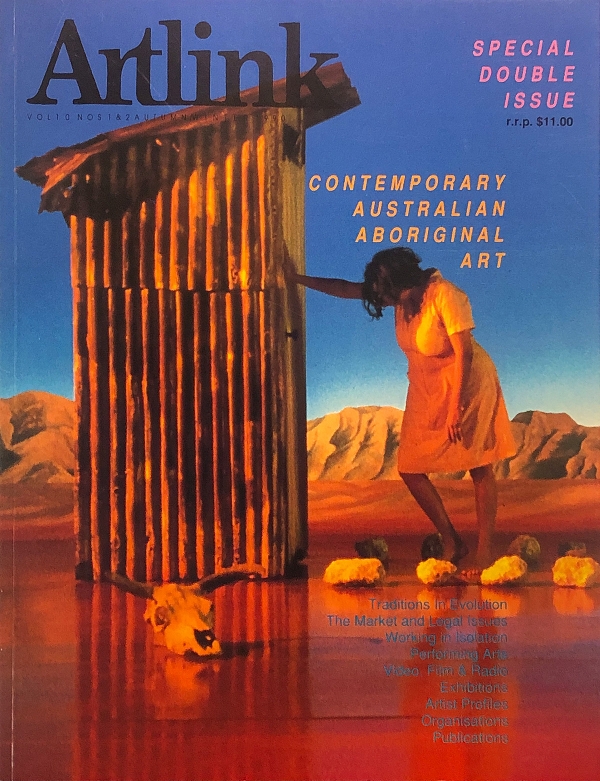

Contemporary Australian Aboriginal Art

Issue 10:1&2 | June 1990

Classic groundbreaking double issue. Reprinted by demand. Looks at traditions in evolution, the role of Art in the survival of the culture, the art market and legal issues, the issues faced by artists working in isolation, indigenous film, video and radio, with a wide range of individual artists profiles and discussions of art practice in remote and urban communities. A unique early documentation of the early days of Aboriginal art in Australia.

In this issue

In 1988 the artists of Ramingining, a remote Central Arnhem Land community, were responsible for perhaps the most-moving political statement made during Australia’s bicentenary year. Djon Mundine tells UK-based anthropologist Howard Morphy, how this extraordinary monument came to be made.

Howard Morphy interviews Djon Mundine at Ramingining in Arnhem Land, Northern Territory.