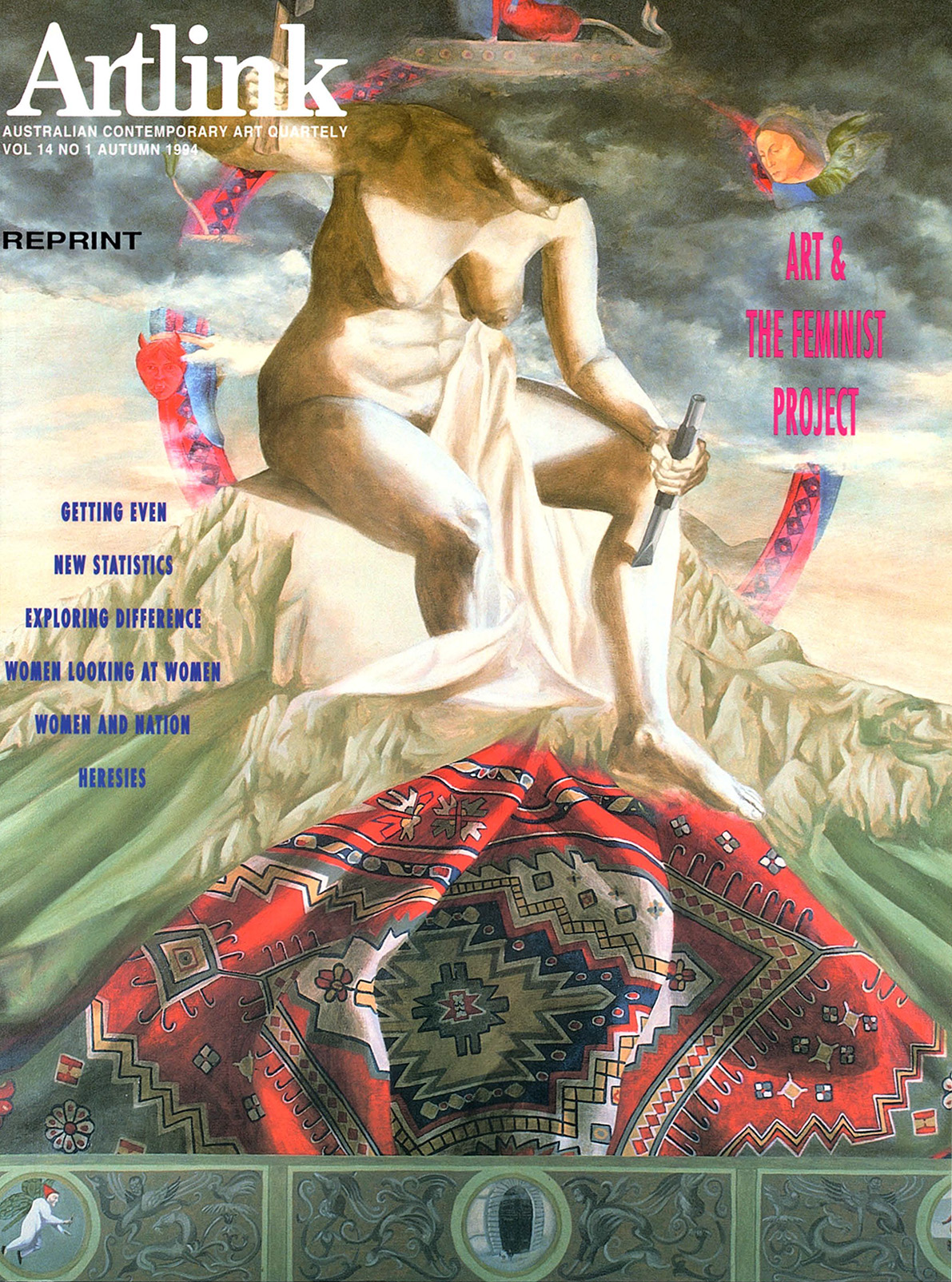

Art & the Feminist Project

Issue 14:1 | March 1994

Very popular issue looking at art and women's issues. Reprinted. Articles examine difference, women looking at women, heresies, women and nation. Includes new statistics. Reviews.

In this issue

Sadomaschism, Art and the Lesbian Sexual revolution

Black leather, blood, piercing and tattooing, glamourised dominance and submission should be approached with political discernment and discrimination.

Shedding Skins: Identity and 'Lesbian' Art Practice

What does it mean to present as a 'lesbian' artist? The very identity categories 'gay', 'lesbian', 'heterosexual' are extremely problematic. Now that 'I' am out, I find that I am in - inside a category that reduces rather than expands possibilities for me, not just as an artist, but as a person.

The Horror of the Prose: Some Reflection on a Paper entitled The Horror of the Gaze

Some reflections on a paper entitled the Horror of the Gaze. Art criticism is, perhaps, an art form and not expected primarily to make sense. There is no consensus about what art is, but we do seem to share an urge to understand what critics say about it.

Update: Projects of Women and Art

A survey of current issues, events and projects with respect to women's art from around Australia.

HER-ESIES Ancient and Modern

"Women in art must look to the future as they have no past" said Mary Cecil Allen at an opening of the Melbourne Society of Women Painters and Sculptors in 1935. A critical examination of the current art practices of women in Australia.

Someday, Somewhere - Women and Nation in International Art

However, feminist artists, curators and writers could collaborate in establishing alternative frameworks for international exhibitions that would render unthinkable the omission of female artists or the implicit erasure of gender as an interpretive key.

The Art World: More Than a Foothold

Australian women artists still see grey skies when they look out of their studio windows. This study examines the experiences of women in the hierarchical Australian contemporary art scene.

What Should We Do With The 'Women and Art' Elective?

Women's courses since the 1970s have become a familiar if marginalised component of most art school curricula, their initial aim being to compensate for the absence of women in the Art History and Theory syllabus and to encourage the development of feminist art practices.

Nourishment for Tough Times: Bring A Plate Conference

Review Conference Bring a Plate: Feminist Cultural Studies Conference University of Melbourne

10-12 December 1993

The Engagement of the Personal

How do we define ourselves? What are the choices for women these days?

Image Bank: The Feminist Project

Presentation and artist statement by contemporary female art practitioners. Women looking as feminist, feminine, female, femme, feminal. Artists featured: Frances Joseph, Angela Stewart, Maryanne Coutts, Noela Hjorth, Jill Kempson, Maria Kuczynska, Rosslynd Piggott, Eugenia Raskopoulos, C. Moore Hardy, Alex Macfadyen, Janet Neilson, Deborah Paauwe, Virginia Barratt, Linda Dement, Susie Hansen, Janina Green, Joy Smith, Madeleine Winch, Kathie Muir, Libby Round, Pam Johnston, Merryn Eirth, Dee Jones, Di Barrett, Frances Phoenix and Ella Dreyfus.

Knocking on the Inside: Heather Ellyard, Annette Bezor, Janette Moore and Anna Platten

Looks at the work of Heather Ellyard, Annette Bezor, Janette Moore, Anna Platten.

The Changing Face of Australian Women

Women from non-English speaking backgrounds are adding another dimension to the picture of women in Australian art. Informed by other cultures and dealing with issues of ethnic difference, the images on these pages create a broader idea of what it is to be an Australian woman.

Fatal Attractions: Women and Technology: Norma Wight, Edite Vidins and Lyndall Milani

Looks at the work of three Queensland artists working in different ways with computers.

Trapped in Paradise - Some Women Artists in Tasmania

The artists were selected because their work embraces not only questions of gender, but also addresses the distinctive duality between the superficial look of things and the complex web of underlying meaning, desire, fear, experience, and memory that they have located and interpreted for us. Featured artists are Jane Eisemann, Jacqui Stockdale, K.T. Prescott, Helen Wright and Megan J Walch.

A View from the Other Side - Five Women West Australian Artists

Looks at the art practice of 5 Western Australian women artists: Helen Taylor, Alison Rowley, Moira Doropoulos, Michelle Elliot and Linda Banazis.

Bad Girls: Institute of Contemporary Art London

Review Bad Girls: Institute of Contemporary Art London 7 October - 5 December 1993. Using glamour, virginity and stardom to attract as wide an audience as possible to a show of supposedly anarchic women artists all hoping to confront notions of sexuality and gender was a smart, if questionable, move....

Speaking the Ineffable: New Directions in Performance Art

Looks at Linda Sproul's 'Listen' and Barbara Campbell's 'Backwash'.

Making (A) Difference: Suffrage Year Celebrations and the Visual Arts in New Zealand

Suffrage year celebrations and the visual arts in New Zealand.

Re-orienting Feminism in Aotearoa

During the past 8 years or so there have been two distinctive strands of activity which women artists have pursued in Aotearoa/New Zealand. Both are concerned with questions of identity. Artists Fiona Pardington, Emily Karaka, Shona Davies, Christine Webster and Robyn Kahukiwa.

Bush Women: Narrative Paintings from Outback Western Australia

Article written with Karen Dayman Works being produced by senior indigenous women artists around Western Australia use figurative elements as well as symbols to doucment their own histories during a period of unprecedented social and environmental upheaval.

Filipina Migranteng Manggagawa: Feminism, Art and Advocacy in the Philippines

Overseas contract workers from the Philippines support their families and their country as whole through many lonely years of exile.

Jillian Davey: Stories on Canvas

Jillian Davey works at the Ernabella Arts Centre on the Pitjantjatjara Lands of the north west of South Australia.

The Price of Liberty

The Women's Art Register contains a public access slide library of 20,000 slides, 14,000 information folders representing (as at 1994) 2,400 Australian based women artists.

Sight Lines

Book review: Sight Lines Women's art and Feminist Perspectives in Australia Sandy Kirby Craftsman House Sydney 1992 RRP $75

Nola Farman: The Challenge Continues

Examination of the art practice of Nola Farman.

Memorial to the Survivors

Discussion of the work of Aboriginal artist Hope Neill

The Amazingness of Women to JUST DO IT

Rural Australia produces resolute women - astute, sensible, profound. This article examines the work of one of a woman from the south west of Western Australia - what influences and inspires her.

Porn Shop Art Adventures

Written with Barbara Holloway Exhibition review Joe Blow: A very erotic art exhibition by Jo Ernst

Adam and Eve Gallery Canberra

December 1993

Surviving the first 12 months: Swing Bridge Art Gallery Dunally

Printmaking and Optimism

Exhibition review I'sland (I'l)n.

Exhibition of prints Long Gallery, Salamanca Arts Centre, Hobart, Tasmania

23 December - 2 January 1994

Far Beyond First Impressions

Order Australis

Dick Bett Gallery, Hobart, Tasmania

August 1993.

A Woman's Story: Hunting Grounds

Fremantle Arts Centre, Western Australia

5 November - 10 December 1993

Modest Perfection

Bunbury Regional Galleries

November 1993

Revelations of a decade

Tangerine Dreams: a matter of Western Australian Style 1970 - 1980 Lawrence Wilson Art Gallery

University of Western Australia

Memories of a Nebula

Fountain installation by Derek Kreckler

Experimental Art Foundation

Adelaide South Australia

2-24 December 1993 and 11-23 January 1994

Different Dreaming

Lap : an installation view. Keitha Phelps

Five Different Homes. Louise Haselton

Contemporary Art Centre

19 November- 12 December 1993

More Light (Goethe's last words)

Craig Andrae Miscellaneous Remarks

Contemporary Art Centre

Adelaide, South Australia

3 September - 3 October 1993

Reaffirming Identity

Fab art: Works by Kerry Giles (Kurwingie)

Gallerie Australis

Adelaide South Australia

23 November - December 1993

En-Gendering Resistance: Opening Moves with Game Girl

All New Gen Game Girl

by VNS Matrix

(Josephine Starrs, Francesca Da Rimini, Julianne Pierce, Virginia Barratt), Experimental Art Foundation

Adelaide South Australia

21 October - 21 November 1993

Artrave