Stories lie heavy across Barkandji Country.[1] They are present in the rustling of the river red gum leaves, hidden like emu in the ruby saltbush and painted in the stars. Stories are woven into the fabric of this place; they connect us to the deep past and the deep future. These stories are a bridge between the generations that have come before, those who walk the lands now, and the generations that will follow.

Barkandji Country lies to the east of Broken Hill, embracing the Barka / Darling River. It is vast and diverse Country, with red desert and black soil made up of rich river deposits over millennia. This Country is alive and colourful, supporting important ecosystems and Barkandji culture which has also shaped Country in return.

The Barka has been in peril many times in recent history. In 2018, and again in 2023, millions of fish floated dead on the surface of the river. Deprived of oxygen the fish had nowhere to go; the gates of the Menindee Weir were closed, inhibiting their ancestral travel routes through the Barka. Rotting fish corpses lay thick on the water. While these events are undoubtedly exacerbated by climate change, to many the blame lies with irrigators upstream and recurrent governments reinforcing the colonial mindset of complete mastery over Country. Instead of working with Country and its abundance as Barkandji always have, recent settlers have dammed, diverted and destroyed the precious waterways. Over and over, Barkandji mob, the people of the Barka, have advocated for their Country and fought for water rights.

ngaratya (together, us group, all in it together) is a love letter expressing the connection between Barkandji people and their Country. Composed of works by Barkandji artists, ngaratya was formed through a series of intentional trips to and with Country. The artists travelled together to Kinchega National Park with its twisting gums, to the Menindee Central School connecting family histories, and to Mutawintji National Park and its rock art galleries. As the curators describe,

Our Country lead the storytelling showing us each where to go. She held and nurtured us, drew us closer together and guided when we were unsure.

These trips inspired the works that are shared through ngaratya, speaking both to the collective experience and the deeply personal connection each artist has with their homelands.

I had the privilege of walking Country with three of the ngaratya artists. I travelled to Barkandji Country in 2021 to interview artists as part of an exhibition curated by Zena Cumpston called Emu Sky.[2] Sitting on the edge of the Barka in Kinchega National Park with renowned artist Uncle Badger Bates, I listened as he explained the vitality of the Barka by tracing its path across his body, from his heart to his fingertips, recalling his Country. Wilcannia is somewhere near his shoulder, Menindee nestled in the crook of his elbow. The Barka is his veins, the lifeblood of this Country, the lifeblood of the people. A pelican swam in the river near us, perhaps waiting to see if we were fishing, or perhaps listening in to the stories Uncle Badger told us. When we left, Zena peppered Uncle Badger with questions about the plants. He led her away to an unassuming quandong tree. This is yours, he told her, and invited her to collect the seeds. Later that night at the Airbnb in Broken Hill, David Doyle came by, and Zena told him about the tree. He knows the one. Of all the quandong in the park, he remembers the small tree just off the path.

These interactions on and with Country are vital to strengthening culture and connecting our often diasporic communities. The process of intentional trips to Country in creating ngaratya manifests in poignant ways throughout. Entering the exhibition at Bunjil Place, visitors are invited into the Welcome Space which invokes the artists’ gatherings during their trips to Country. We are invited to share their journeys through images of Country, family photos and carefully selected resources. The welcome space is curtained by calico drapes, with a large couch and central sitting area. A slide show is projected against the calico, showing images from the artists’ time on Country. Sounds of Country call us into the space beyond, where glimpses of the work emerge from behind the curtains.

Speaking as the project’s curators, Nici and Zena Cumpston, joined by their cousin and fellow artist Raymond Zada, describe David Doyle as the centre of the group. His work accordingly takes centre-stage in ngaratya. The collection of river red gum–kamuru–artefacts made by Doyle speak to the ways in which Barkandji people have always worked with Country. Kamuru can be used for many things and lasts across many generations. It provides warmth and shelter, its bark can be harvested for canoe and shields in a way that sustains the life of the tree, and the trees stand as living sentinels over birth and death. Above Doyle’s artefacts, a fishing net created by all the artists is suspended, drawing the eye up and across the room, connecting the artworks and the makers. The works are linked through shared experience and shared culture, but each express a unique voice. Travelling to the hometowns of dear friends, there are always places they want to show you: the milk bar with its white paper bags of lollies, the house their Nanna lived in, the public place they caused a ruckus in as a teenager. ngaratya feels like that, a series of vignettes into memories of place, warm and complicated, wrapped up in deep history and retrospection.

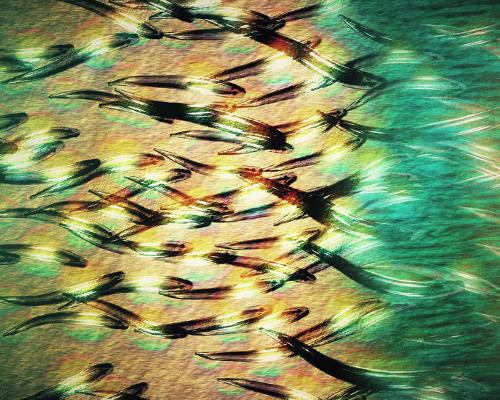

Nici Cumpston’s photographic series Old Mutawintji Gorge I – VII (2023) is a masterful meditation on Country. Carefully hand-coloured, the photographs reflect both what is seen and what is felt, the physical and spiritual manifestations of Country. Taken on site, but finished in the studio, Cumpston imbues the work with joy and reverence, drawing from the memory of place. The play of light and shadow is enhanced through Cumpston’s technique, a glimpse of the stories that are held in this place of ceremony. Light and shadow also feature in Adrianne Semmens' moving image work, kuntyiri, shadow, reflection (2023). Semmens brings together her past and present through dance, personal memories and connections spanning time and geography, symbolically held together by string. Much like Uncle Badgers veins, Semmens performs an alchemy on the string—it is a map, it is a physical tether between the present and the past, and it is the lifeblood of Barkandji people.

The past is ever present across ngaratya, profoundly expressed in Raymond Zada’s Bloodline (2023), as the artist describes ‘...it is your parents and their parents and their parents and their parents . . . for ten generations.’ Two thousand and forty‑two individual figures represent any one person’s immediate ancestors, etched into acrylic panels. The panels form the flowing Barka, a striking red that connects the river to the people, the blood that flows as the river flows. The figures represent the ancestral ties we all hold and the connections we have to place and each other. Our peoples have been here longer than modern science can fathom, upwards of 80,000 years or 3,000 generations. These multitudes are also reflected in Kent Morris’ kaleidoscopic Karta‑kartaka (2023) series. Morris transforms photographs taken at Mutawintji of karta-kartaka pink cockatoo into stories expressing the complex web of knowledge passed down through ancestral wisdom. A series of six still images are displayed beside a large looping video. Reminiscent of a child’s magic eye book, the images morph from recognisable shapes to interconnected patterns speaking to the infinite connections of Country.

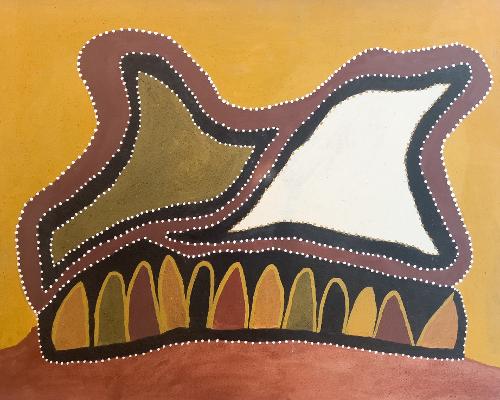

Abundance is celebrated throughout ngaratya: in the abundant uses of kamuru in Doyle’s work, the abundance of colour in the bright flashes of karta-kartaka from Morris, and the abundance of deep time knowledge in the stories shared by Zada, Semmens and Nici Cumpston. Zena Cumpston also highlights this richness, and the absurdity that the plentiful bounty of Country is unattainable to many of its countrymen and women. Cumpston’s collection of lino-prints are a portal into the richness of plants across Barkandji Country, provoking questions on the consumption and commercialisation of Aboriginal foods. Bush foods are an 80-million-dollar industry, with less than two per cent benefiting Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities.

This contemporary dearth is contrasted with historic profusion, shown in a photograph of Barkandji mob from 1879. Central within the photo are Mary, Jacob and their daughter Doughboy surrounded by resources from Country. Explained by Cumpston in the room sheet, the image unfolds with close and careful observation. Plants and other resources are used in ingenious ways, not for profiteering but to sustain complex social structures, always in reverence to Country. Thinking of Zada’s generations, the rapidness of the removal of our peoples from Country and its resources is confronting. Often, we as Aboriginal people are asked to perform our Aboriginality without being given space to connect with Country and practice culture. We are expected to hold all the western qualifications as well as be cultural experts, without having the space to foster our connections to kin and intergenerational knowledge. ngaratya foregrounds coming together, drawing from the richness of the thousands of ancestors who have come before, and building on the legacy of activism for Country. This creative process is nourishment for artists, providing vital space for blackfella business.

I had the privilege of attending the opening of ngaratya at Bunjil Place. Breastfeeding my five-week-old son, I listened to the performance of No Baaka, No Barkindji by Leroy Johnson and the Waterbag Band. The song speaks to the deep connection between the health of people and the health of Country, they sing ‘When that dam bursts, you and I will both be free’. We are reminded by Elders that when we care for Country, Country cares for us, that the way we nourish Country is the way Country can nourish us in return. Visitors to the opening were gifted with river mint, a delicious plant rich with antioxidant and antimicrobial properties. In accepting this gift, we accept to care for this plant as part of Country.

Footnotes

- ^ A note on spelling: Aboriginal languages have only recently been written, retro-fitted with an alphabet that doesn’t necessarily work for our ancestral sounds. There are several common spellings of Barkandji/Barkindji and Barka/Baaka

- ^ Emu Sky was exhibited at the Old Quad, Parkville Campus at The University of Melbourne, 15 February – 21 August 2022.