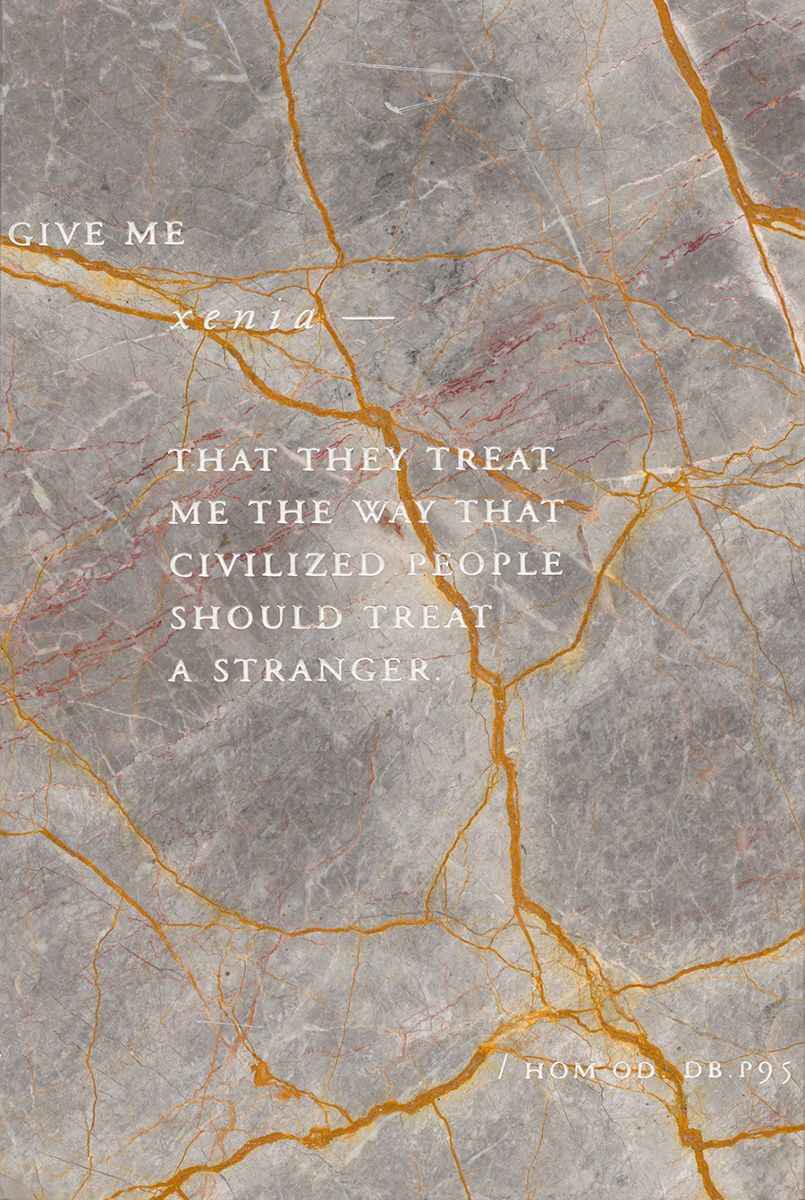

At the media preview for the 2022 Adelaide Biennial Free/State at the Art Gallery of South Australia I was introduced to an ABC journalist whose disaster-rhetoric ran along the lines of ‘forget climate change, now it’s nuclear catastrophe’: we were standing beside the work of Ukrainian-born Stanislava Pinchuk, whose homeland state was invaded by Russian troops a week earlier. Cameras and mics pressed in on the artist, her Wine Dark Sea (2021) installation of dethroned marble plinths engraved with Homeric quotations presenting a sombre monument. Concurrently, northern NSW and Queensland were under deluge as ‘once in a thousand-year floods’ chimed with the post-pandemic re-openings of festivals and art fairs, biennales and dancing. At the time of writing, the extent of the flood damage is hard to fathom, but repair will take years and the rain keeps falling.

Against these pressing real- world agonies, Artlink’s thematic model engages the historical and the futuristic, and there is an unmistakable pattern. A decade ago, the cover of Disaster & Fortitude (32:4, 2012) read like today’s to-do list: ‘visualising disaster, the war on climate change, nuclear accidents, fighting fracking, fire/flood/quakes, the necessity of resilience’. As Malcolm McKinnon wrote in his feature “Promoting the Long View”, ‘Australia [...] is a nation of champion forgetters. We seem to have an unfortunate indifference to our own history [...] We can also discover within our archives an epic repetition of the same passionate rhetoric every time the great fire flume wreaks havoc upon us.’ His article went on to detail Victorian artists’ inventive responses to the 2009 Black Saturday fires in the Illuminated by Fire project. In seasonal fashion It’s Time (40:1, 2020) added to Artlink’s archive of ‘passionate rhetoric’ in ultimatums for anyone with the time to read. It came at the end of the devastating 2019–2020 summer of fire when COVID-19 was breaking news.

Less pressing, but intrinsically valuable for an art magazine, is the more introspective nature of Art / Write / Read. This frictional matching of noun and verbs implies the connections between art, writers, and readers. Or I hope that’s implied: it depends on how you read. It’s a theme I’ve been haunted by in my (still tender) tenure as Editor, but like big weather, it’s not new. In 2009, Changing Climates in Arts Publishing (29:4) addressed our industry by collating information in a way now largely superseded by online platforms. Perennial concern about the state of art writing and publishing appears thicker than ever, while its most esteemed sub- genre, criticism, appears to be wasting away. Or that’s the word on the virtual streets as the topic has generated numerous online sessions, conferences and publications in recent years.

One of the more substantial outcomes—if you can call a paperback ‘thick’—is Art Writing in Crisis (2021), edited by Brad Haylock

and Megan Patty and reviewed in this issue. The anthology spans the apocalyptic scenography of the pas two years with the inevitable flow- on effects on art writing’s industry status, its methodologies, and its variant formalisms. The editors have commissioned their writers with flair and diversity in mind, though artist-writers barely make the cut.

Among the provocations art writing raise is an artists’ involvement in their own canonisation and the role key interlocutors—art historians, critics and curators—play. It’s a question Wes Hill’s extended review of Gordon Bennett: Selected Writings takes up: the artist’s ambivalence in managing interpretations of his work. An avid and wide-ranging critical reader, Bennett’s star rose high without the leg-up that social media provides, and his posthumously exhibited and published works—notably writings and drawings—have only contributed to his veneration. It’s the substantial material he leaves behind in art, words and language, ‘wrestling with theory from the inside out’, that brings his success home to readers.

As a counter example, the retrospective reverence for Philippa Cullen evolves with barely a trace in the physical archive. This is partly due to her short life and ephemeral practice, but as Daniel Mudie Cunningham reveals, there’s a fledgling industry in contemporary performance art and its writing that authenticates her ghostly innovations. While Cullen’s ambitions and potential will never really be knowable through the speculations of others, Bidjara artist D Harding composes their own reception through carefully chosen projects, strategically framed by scholarship. It was Harding who commissioned Ian McLean to write on their current curatorial endeavour in Treviso, Italy, in Luciano Benetton’s satellite contribution to the Venice Biennale: the text was printed as a takeaway poster, vicariously granting the art historian temporary residence as a relational artist.

In an essay devoted to an obscure late Renaissance painting by Orazio Samacchini hung high in the Art Gallery of South Australia, Michael Newall applies a classical iconographic and iconological analysis. It’s a lesson for secular audiences whose hagiography typically extends no further than contemporary artists. While such Panofskian studies and traditional art histories are diminishing in Australian universities, escalated during the cost-cutting opportunities delivered by COVID-19, Aneta Trajkoski argues for more diversity in art historical writing and its capture in academic research metrics.

Meanwhile, as Kit Messham-Muir relates, Art Theory (his capitals) has long-since cleared the building. That has not stopped theory washing up on the banks where art practice and academic research meet, as Marielle Soni’s response to MUMAs Language is a River suggests. Ultimately, there’s a raft of alternative streams to write from and a range of tools to use. Independent curator Sebastian Goldspink shares his personal views on curating and writing in relation to Free/State and the contradictions implied in the title, but in truth, the idea of ‘free’ or autonomous curators or critics is a fiction. In state sanctioned public institutions, caution is paramount. Imagine if you will a silver gelatin photograph of the National Gallery of Australia’s interior shot by Max Dupain. Now use it to frame Elspeth Pitt’s essay on the curator’s responsibilities to care, ethics and judgment while holding their own subjectivity up to the light. When public relations are closely entwined with institutional image permissions, visualisation is a simpler form of reproduction

In classifications of art writing, there are muddy distinctions between the benign review and the rigorous art of criticism. Where the writer is positioned geographically and generationally makes a conceivable difference. Olivia Bennett’s protagonists exist in an online metaverse where the speed of commentary and the anonymity of critique risks the ultimate obliteration of the text, while Western Australia’s pandemic-amplified isolation gives John Mateer grist for his argument: to reinstate the critic’s innocence. Ironically, despite differences in age and environment, both writers probe similar problems.

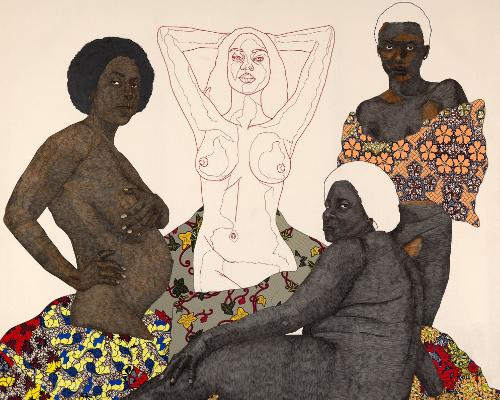

On Jinibara Country, Dominique Chen’s account of Libby Harward’s performative practice moves outside conventional institutional boundaries, reshaping the terms for a new wave of Indigenous academics. There is a tendency in local art discourse to exhaust the binaries of Anglo- European coloniser and Indigenous Australians in a metaphorical ouroboros. Tactically poetic, Brian Obiri-Asare pulls gently at a thread in his discussion of Pierre Mukeba’s paintings to ask a question on blackness we all like to think we have the quick answer to.

Géricault’s Raft of the Medusa (1819) and Norman Tindale’s map of Indigenous language groups (more widely known today as the AIATSIS map of Aboriginal Australia) are the historical documents Dean Cross uses to construct gunalgunal (contracted ground) (2022). Detailed on our cover, it illustrates the perpetual readings made possible by the archive (and the designer’s cropping tool), and how new meanings can be wrought from the wreckage and the riches. In this vein, Artlink’s open invitation to writers to engage with our archive as our forty-year anniversary sailed past sees emerging writers Belle Beasley dipping a toe into dance writing and Grace Slonim arguing the case for more fearless and better funded arts writing. There’s also a moment for good grace: Artlink is still afloat despite the widely condemned Australia Council cuts to arts publications in 2020, and the rest. Along with the print edition of Art / Write / Read we are publishing the first in a series of long-form essays incorporating the Artlink back-list, and Jacqueline Millner’s reflections on the writer’s marathon (with a feminist twist) is an apt leader.

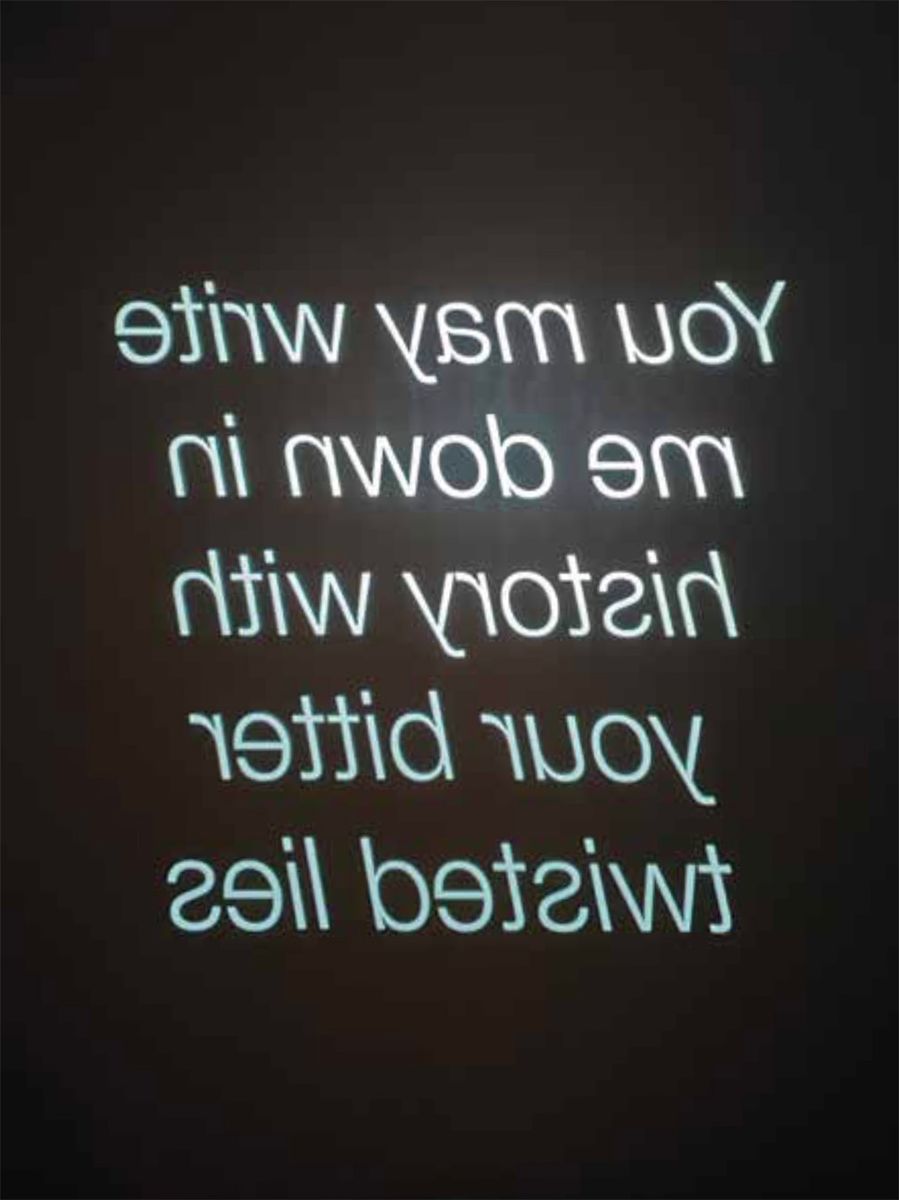

Incidentally, Julie Rrap’s installation Write Me (2022) covers similar terrain, though the marathon event is Zoom and the words of others complete the dialogue. Her flickering work captured my attention during a long-overdue visit to Kaurna land where I raided gallery basements for images that pictured writing. It’s no coincidence that Rrap loves to dance.