There is nothing like time-based art exhibitions to make us question the use of our own, whether readers or audiences. Is the visitor taken for granted when curating time-based shows in a time-poor world? It is somewhat of a contradiction that the artist creates, in many instances, linear works bound as they are by time, relying on a beginning, a middle, an end. For the reality of a visitor’s experience is that they encounter the artwork at any random point within its duration. We might enter three quarters of the way through, we might not stay for the whole thing, or if we do (like I do) we might experience the last twelve minutes of the work, and then watch the beginning. Out of sequence of expectation, the way the artwork and I meet is not necessarily the controlled unfurling of film (or data stream) of the artist’s intention. Akin to navigating a cocktail party, sashaying in and out of multiple conversations at different times, interrupting one in the middle, getting snippets of it, not sure if it’s the appropriate time to move on. An uncomfortable truth is that many don’t stay for the whole party. Perhaps not merely due to being ‘busy’, but because we are losing our ability to focus, our attention spans are depleting. It is rather ironic considering it is this medium that is the culprit at play— technology itself. However, at a total time commitment of under two hours Language is a River presents seven artworks by six artists, manageable durations, respectfully individuated (with only one instance of dual audio volumes cutting in on each other).

Contemporary digital culture is well referenced throughout. Akil Ahamat’s Muscular Dreams (2016) is a short YouTube-esque ASMR first person reading of a scene from the widely popular and oft meta referenced sports-comedy Space Jam (1996). The fetishizing wispy voice and simple video graphic could be very comfortable as a social media creation for devotees of ASMR (autonomous sensory meridian response, typically soft vocal whispering that triggers a tangible physical euphoric tingling, with tens of millions of seemingly innocuous videos online tapping into its erotic potential and double entendres). Muscular Dreams is quirky, amusing, quizzical, likeable; it won the artist the John Fries art award in 2018. Ahamat’s later work So the space between us can stay soft (2018), more successfully achieves a deeper response upon viewing.

Language is a River curated by MUMA’s Hannah Mathews, with catalogue text by Melissa Ratliff, set itself a lofty goal but felt self-referential, and self-consciously indebted to the reckoning of institutional critical theory. It explored the role of language as an instrument of creating identity within the construct of artists who use language as a medium within video/audio contexts. Ultimately, it appears reproachful of language, exploring language’s failings without celebrating its wonders. With such a weighty topic so central to our species and so complex, the burden fell hard on seven works by six artists.

An important inclusion was Charlotte Prodger’s 2018 Turner Prize winning work Bridgit (2016). A single channel work filmed on the artist’s iPhone, an autobiographical voiceover reads excerpts of her experiences and memories of growing up gay in the Scottish Highlands. The images are beautiful, painterly, mesmeric—the sense of place and subject somewhat abstracted. A large screen piece is richly cinematic, and MUMA provides an important opportunity for Melbourne to view it in full glory rather than the micro-screens of nearly two years of lockdowns.

Other international artists with significant reputations are Wu Tsang (USA) and Shen Xin (China/USA/UK). Tsang’s Duilian (2016) is a short film in keeping with their practice of performance and filmmaking. Featuring themselves and their real-life partner as protagonists, the artist appropriates, reinterprets and re-enacts the historical story of Qiu Jin (1875–1907), poet and revolutionary, and calligrapher Wu Zhiying (1868–1934): women, lovers, artists. A story of determination, politics and tragedy, Tsang interprets through a contemporary position of queer identity politics. It is the most traditionally narrative-based work in the show, with the characters’ dialogue (in English) interspersed with choregraphed performance and Chinese voiceovers (the poetry of Qiu Jin). At times the dual audio overlaps, so the viewer cannot quite decipher what is being said in either language. This confusion of language is lessened to curious ambiguity because of the richness of the imagery, beauty of the choreography and the filmic nature allowing a voyeuristic gaze upon their bodies and intimacy of their relationship. The artist and their partner utilise their bodies as media by placing themselves within the work, visibly Trans, which presents another layering of language, albeit a gendering and visual one.

Shen Xin’s Commerce des Esprits (2018) is a thoroughly whole and yet layered work, a satisfying sculptural installation ‘doubling’ as a four-channel video. Each channel plays on the outer surface of a large-scale panel wall, the four walls collapse inwards to buttress each at the top edges, creating a fallen room structure. It’s one that we cannot enter, but only walk around. At once personal, sociological, cultural, philosophical and aesthetic, a globally transiting work seen and heard here in an Australian context. I was compelled to stand at the back of the work where the text screens were reading in English because, as a monolingual, I am excluded from parts of the work. Exactly the point: how differently the work would have been interpreted in (for example) its cosmopolitan setting of Art Basel Hong Kong in 2018.

Two works created locally and specifically for this exhibition were standouts in terms of their clarity of purpose. Archie Barry’s work Scaffolding (Preface) (2021), questions language’s potential for any further development. By exploring the limitations of language to connect individuals, the artist intimates an evolution of language much as life’s origins and (hopefully) continuations. Filmic sequences of water, single-cell life forms, rapidly multiplying cells, a barbed fence barrier with a floating, rotating, animated faceless head and long blonde hair dominates. Various sounds emanate (reminiscent of sound energy waves currently popular on Instagram), human voices sing. Text within the video goes someway to connect the artist’s intent with the viewer’s experience beyond what is image. The irony is not lost on me. The visuals suggest, but the written word within the film and accompanying catalogue text by Pip Wallis is what enables me to understand the full complexity and rousing possibilities of Barry’s work. So, perhaps after all, language is not such the ‘impediment’ to human connection and cohesion as the curatorial prompt might suggest.

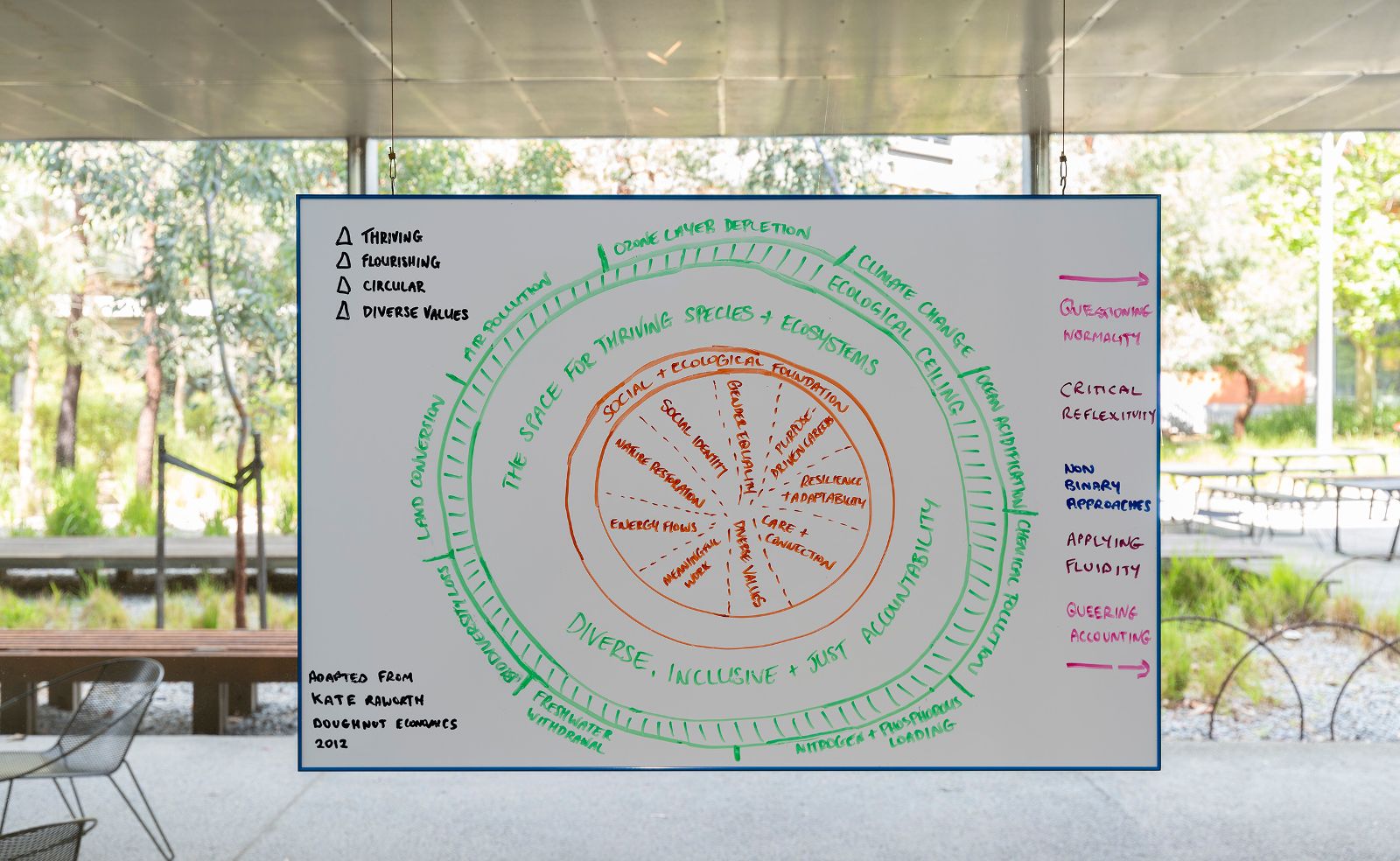

Sarah Rodigari’s Towards an Affective Measure (2021) is not much to look at, but one that inspired engagement, curiosity and swift understanding. A few whiteboards with words and diagrams, some carpet tiles and a ceiling speaker pendant from which a voice narrates a story and an audio exposition subvert the language of economics to transform accounting terms into personified characters. ‘Profit’ is the protagonist, her story full of emotional context and attempts to understand her place in the world. We follow a short journey of Profit’s awakening, awareness of who she is and what makes her valuable. ‘Profit has stopped believing in progress’. Clearly this language expresses the values of economics and transgresses values of human identity. It permeates globally, pushing for the continual profit growth, which is bursting the planet at its seams. I am relieved to see reference to the climate crisis: Accounting becomes Accountability in Rodigari’s work. The artist’s interdisciplinary and collaborative approach includes input from Queering Accounting with whiteboard thought provocation notes such as ‘Non Binary Approaches’, ‘Applying Fluidity’, ‘Thriving, Flourishing, Circular, Diverse Values’.

Language is a River presents a fascinating subject which has not been explored to its multifarious potentialities. With such a limitless topic it might be an unfeasible expectation, but what strikes me as gaping omissions are the semantics of the urgent climate crisis and our current pandemic. The rise of the right wing, anti-vax, anti-science (pilfering the lexicon of science); even the political rhetoric within government and parliament is bordering on eugenics. ‘Open at all costs’ can be translated as some lives are tradeable: the chronically ill, the aged, the disabled, the physically vulnerable. In this latter category myself, heading out with mask on, sanitiser, risking the crowds, I experienced an exhibition detached from its time, imagined before the age of COVID-19. The skewing of language in the pandemic and the undermining corruption of the language of science are overlooked, but the dilemma remains time. Artwork depending on the temporal as a medium demands more of the viewer, and looking out at the state of humanity, time is against us.