‘Please don’t quote any of this scribble!’[1]

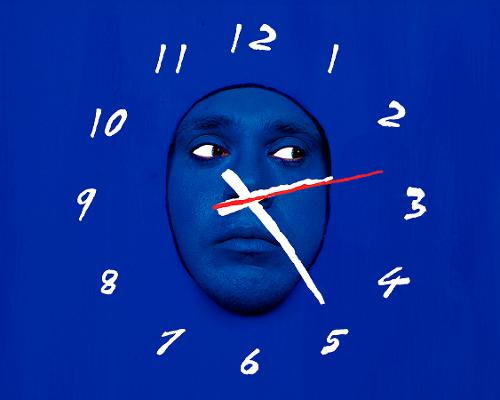

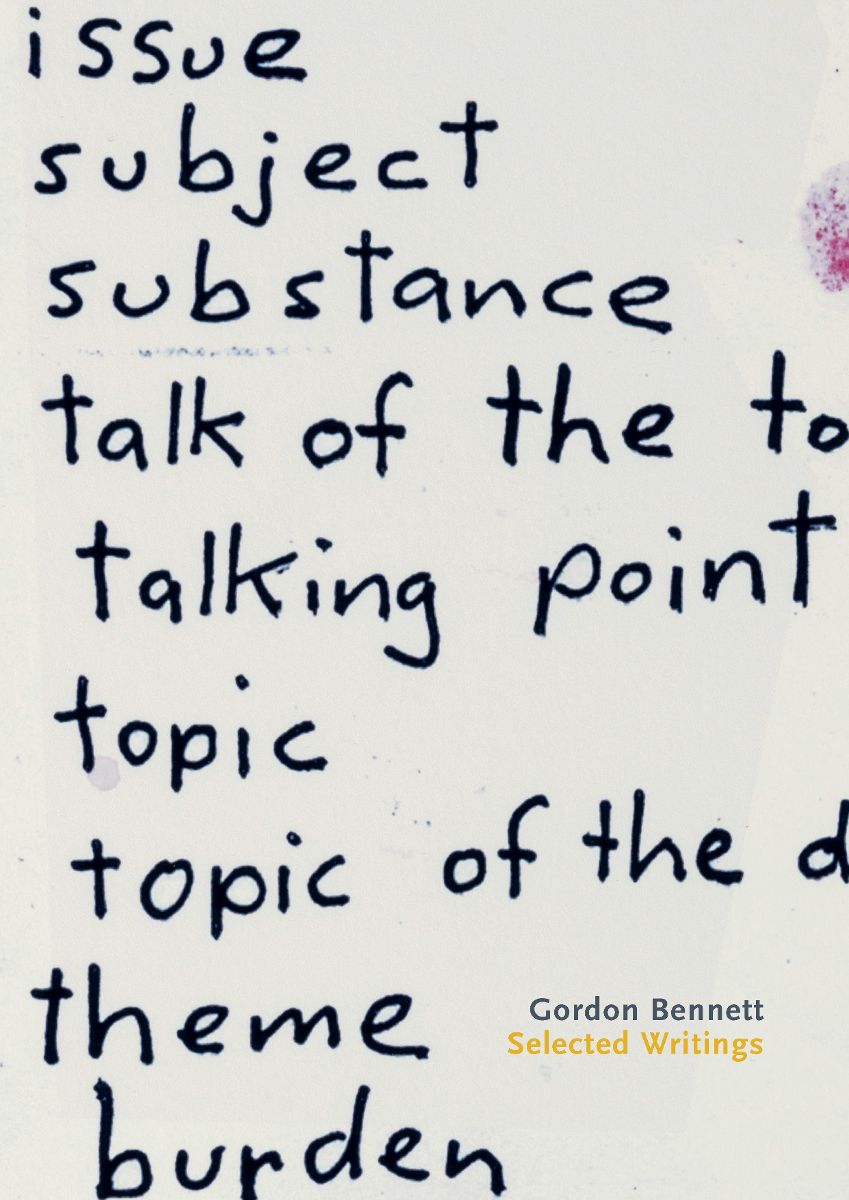

As soon as it was published, Gordon Bennett: Selected Writings seemed a vital resource for anyone interested in Australian postcolonial art history, or simply good art. Since his death in 2014, Gordon Bennett has become a legendary figure whose reputation is likely only to grow; ‘the first artist to explore our Indigenous past using conceptual art techniques’ according to his gallerist, the incisive Josh Milani.[2] Foregrounding his critical voice, Bennett was a driving force behind Brisbane becoming what used to be called the ‘urban Aboriginal art capital of Australia.’[3] He inspired a generation of artists after him to speak back to the art-historical discourses and art-institutional divisions limiting Indigenous representation, embodying what Terry Smith calls ‘a shout from the silenced.’[4]

Like the conceptualists before him, Bennett set out to blur art, discourse and politics. He followed in the footsteps of artists such as the American Adrian Piper, who from the late 1960s probed the divisions of labour separating artist and social critic. Piper conceived of art institutions as ‘political arenas in which strategies of confrontation and avoidance are calculated, diplomacy is practised and weaponry is tested, all in the service of divergent, and often conflicting, interests.’[5] Her emphasis on the visual pathology of both artistic and racist categorisation inspired Bennett, which he articulated in his most widely read essay Manifest Toe (1996). This essay has been re-published in Selected Writings alongside lesser-known essays, interviews, unpublished correspondences, private notes and collected quotes, compiled by Angela Goddard and Tim Riley Walsh in consultation with the artist’s estate.

Jointly published by Griffith University Art Museum and Power Publications, the book focuses on Bennett’s writings to reveal new tidbits about his artistic anxieties, preoccupations and deliberations. Unlike, say, Mike Kelley’s book of essays, Foul Perfection (2003), Bennett’s perspective is more eye-of-the-storm than cultural survey, with many of the texts reading like earnest artist statements in various guises. Clearly, the artist collected his ideas as ammunition against the narrow-mindedness he experienced in working-class, middle-class and upper-class spheres, graduating from racism in the blue-collar workforce to racist and ethnographic stereotyping in the art world.

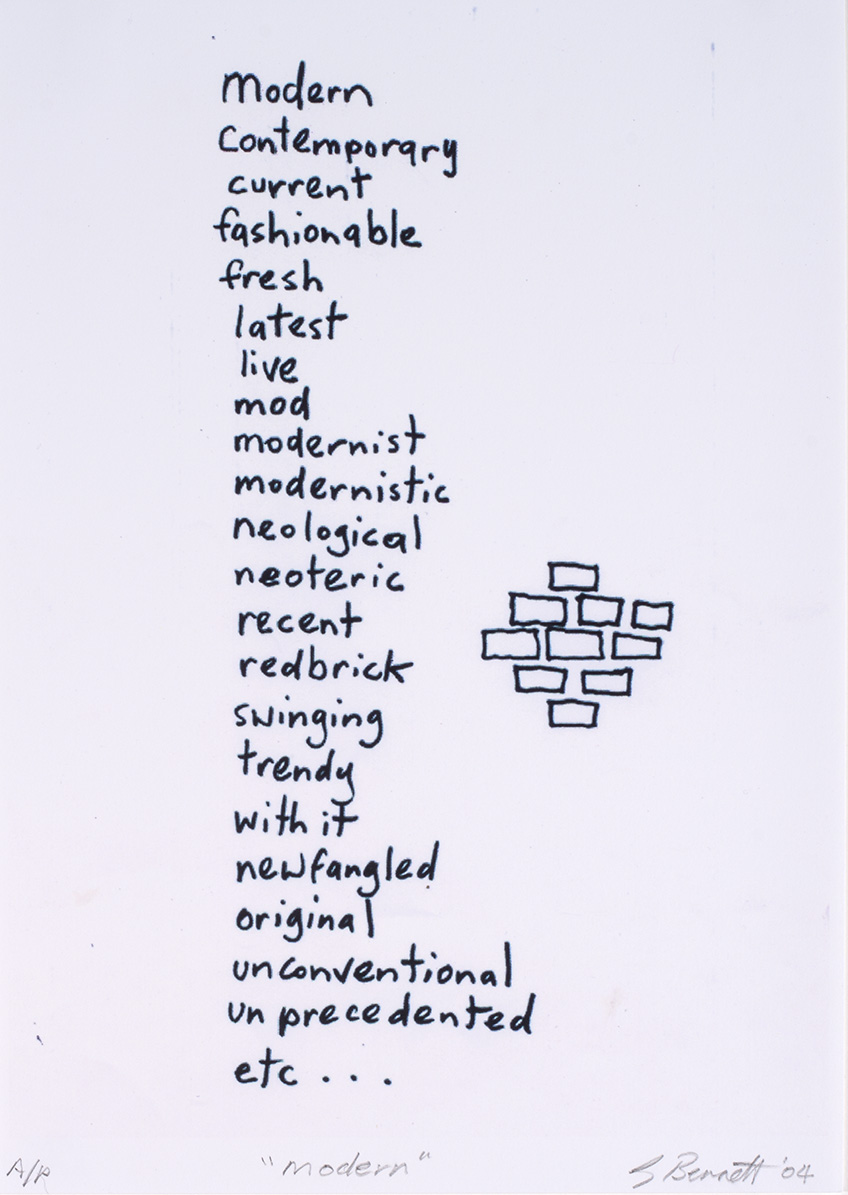

Smith has claimed that Bennett’s conceptual approach was as ‘anti-Postmodernist’ as it was ‘anti-racist.’[6] But, apart from Brook Andrew, few Australian artists working in the post-colonial field have been as well-versed in postmodern theory as Bennett. In toto his writings reveal his wrestling with theory from the inside out. Rather than using the global import of postmodernism to prop up a new aesthetic manifesto (or ‘manifest-toe’), his wide-ranging references to philosophy, cultural studies, anthropology and art history often have personal geneses. Discursive ideas were tools for him to probe his relatively late exploration of his Indigenous identity; an exploration that, through art, became liberated from ‘the binary prison of self and other.’[7] To say that Bennett was ‘anti-Postmodernist’ is to say he was interested in how the textual plays of postmodern art were not, in fact, purely rhetorical. He described his approach in a 1991 letter as ‘an exorcism of the personal,’ underlining the moral implications at play in post-Pictures strategies of fragmentation, excerptation and citation.[8]

Most of Bennett’s texts were written in the 1990s, so Selected Writings allows us to take in that decade from the artist’s point of view. It was a time when ‘reconciliation’ was added to the postmodern canon, despite its frequent appearance as cross-cultural confrontation. It was a decade of postcolonial reckonings, advances in Indigenous land rights, Creative Nation policy rationales, and the start of the melting-pot biennialism we are now accustomed to: globe-trotting artists and curators caught up in worldly, biospheric themes. It was also a time of cynicism towards such things, with artists taking up low-fi, Grunge and abject forms to express what Hal Foster describes as ‘fatigue with the politics of difference.’[9] Fittingly, Bennett spent the start of the decade experiencing what it was like to be an Australian abroad. As winner of the 1991 Moët & Chandon Australian Art Fellowship he spent nearly a year in the French village of Hautvillers, which, as his writings attest to, sharpened his ambition and thematic focus.

In a 1992 letter from Hautvillers to fellow artist Eugene Carchesio, we learn that Bennett’s idea to put a moratorium on giving artist talks was inspired by him seeing a Marcel Broodthaers retrospective in Paris. Encouraged to participate in promotional interviews in France with visiting journalists from Europe and Australia, in response, Bennett conceived of a ‘“non-performance” clampdown on giving public talks.[10] This ‘clampdown’ eventually extended to writing about his own work; however, if nothing else, Selected Writings attests to Bennett’s struggle to keep quiet about his work for much of the decade. To Carchesio, he writes:

I had in mind a project, a ‘non-action’ of say, five years duration, to begin when I return to the old country (and it is my old country). Over this five years, I intend to say nothing about my work other than what I have already said in the past (it has become a matter of saying the same things in different ways anyway, so nothing will be lost in this practice).[11]

Bennett’s new vow of silence stemmed as much from his belief in the generative effects of ambiguity as it did from the anxiety of public display (and the sometimes hostile interrogations that came with the postcolonial territory). He admired the Belgian Broodthaers, who, dissatisfied with modernity’s progressive ideals, used poetic-obscurantist strategies to speak to art’s economic and ideologically driven circuits of distribution, production and reception. However, compared to Broodthaers, poetic ambiguity for Bennett was a double-edged sword. As much as it can generate contemplation in viewers, it can also produce an air of complacency, conflicting with what he saw as his critical responsibilities.

In a 1996 letter in reply to an enthusiastic South Australian art student, Bennett writes: ‘Poetics is never clear, but ambiguous which increases the possibilities for meaningful engagement and demands the viewer to think.’[12] Tellingly, this endorsement of ambiguity comes after a passage in which he admonishes the student for labelling him an ‘Aboriginal’ artist. He states:

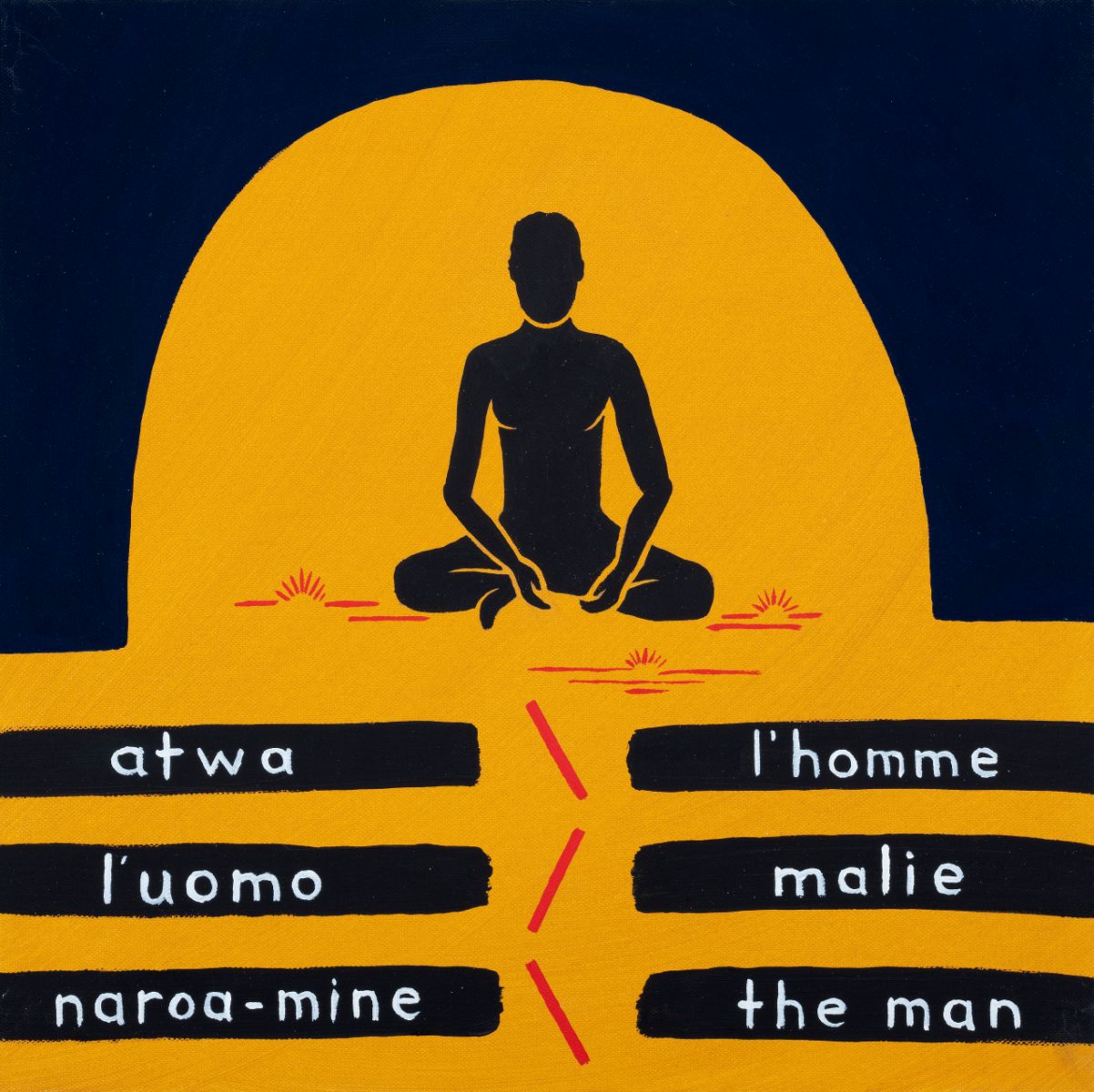

Given my cultural heritage and development as a person within an Australian context, I must point out how such a reductive adjective is not appropriate. It denies my Anglo-Celtic heritage—which is what I grew up with and which was the culture into which I was socialised. I refuse to dump ‘one’ culture for another as I have refused to deny my Aboriginal cultural heritage. I remain Anglo/Celtic/Aboriginal, but I don’t believe any artist should be identified by race.[13]

The struggle between poetics and assertion—or sensibility and identification—pervades Selected Writings, just as it does Bennett’s work. Aboriginality figures in his practice as a knotty signifier just as much as it appears as a clear source of reclamation and ancestral pride. In a 2001 letter to the art historian Ian McLean, Bennett writes that, for him, ‘“in-between” space is important.’[14] In choosing to make art allegorically by juxtaposing assorted pre-existing imagery, he intended for historical meaning to become ‘fragmented and recontextualised to form new relationships and possibilities for the generation of nuance.’[15] In Bennett’s writings, whether as unpublished responses to newspaper articles or private notes, the artist is constantly asking himself if in-betweenness and nuance are enough when one also wants to challenge stereotypes and change social expectations.

Is a base essentialism required of works that explicitly seek to effect change in the world? Bennett waivers on this, which is why, I think, the work he left behind can be so affecting—like the work of an artist in conflict with himself. He claims in an interview that he is ‘too self-aware’ to want to be pinned down, yet he also wants his work to be canonised enough for it to be circulated in high school textbooks, where much of his early imagery was derived.[16] Fighting against the historical ignorance that breeds racism, as an identity-artist, identity is conceived by Bennett not as self-assertion but a line of questioning, ‘through which people might start to depart from the historical limits of their identifications.’[17]

Passages like this remind me of Stan Grant’s short book On Identity (2019), which implores the reader to be wary of identity proclamations in which ‘there can only be difference.’[18] Grant stresses the importance of family, ancestry and familial responsibility yet cites the need for a larger, more fundamental belief in humanity and love. Ultimately, Grant endorses freedom from identity—to be proud of one’s heritage and at the same time be allowed to live in exile from identity categorisations; to live as both self and other. He writes:

Are you Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander? A nation that has never really known what to call someone like me has at times wished us to disappear. Now it wants to settle the matter: yes or no. […] As much as I may be tempted by the slogans of ‘black pride,’ ‘black is beautiful,’ yes, even in our time, ‘black lives matter’—so urgent, so necessary, so righteous—I stop short. I remind myself that even with the best intentions the solitarist political identity can put us on a slow train to tyranny.[19]

Bennett walked a similar line between being accountable to his ancestry on both sides and being accountable to a larger, more humanist sense of self (compare Grant’s sentiments with this from Manifest Toe: ‘If I were to choose a single word to describe my underlying drive it would be freedom.’).[20] In an interview with Chris McAuliffe, which first appeared in Rex Butler’s What is Appropriation? (1996), Bennett states that, when it comes to identity, the fact of him being human is about as fixed as he is willing to be. When pressed by McAuliffe that this means he has ‘chosen a particular discourse—the humanist discourse,’ the artist characteristically sidesteps by claiming that, philosophically speaking, he doesn’t ‘choose’ anything: ‘one day you might be one thing and make a stance, and the next day, after reading more information, you might totally change your mind.’[21]

Hints of contrarianism punctuate Bennett’s sincerity, evoking Dylanesque alternations between authenticity and fabulation, social justice and sheer formal inventiveness. In embracing the gaps between words and images, Bennett fashioned a kind of ‘identity poetics,’ advocating an awareness of historical/cultural context but not a political identity as such. In one moment he wants to undermine Kazimir Malevich’s spiritual universalism by juxtaposing Black Square (1915) with the ‘physical realism’ of black cultural signifiers.[22] The next moment he yearns for the sort of universalism that could free his work from identitarian reductionism: ‘I wish I could get away with a statement like Emily Kngwarreye and say the work is about a ‘whole lot, everything.’[23]

Bennett questioned the ways in which history defines his identity, but, as Milani’s quote at the start of this essay makes clear, he also questioned the ways in which history defines ‘us’—black, white and in-between, hinting at a collective stake in the question of Aboriginality. In this Bennett contrasts with an artist such as Richard Bell, who, fascinating in his own right, appears less internally conflicted by the idea of an art purpose-built for a political identity. In other words, Bennett was suspicious of his iconoclastic signifiers becoming hitched to an authoritative and professional political voice. He explains in a 2007 interview:

I am an artist first and not a professional ‘Aborigine.’ I found people were always confusing me as a person with the content of my work. While it is true that most of my work has been autobiographical, I’m still separate from it.[24]

He goes on to clarify that his abstract works in the 2000s, the underrated Stripe (2003–08) series, helped him realise how all of his work revolves around abstraction in some form. ‘Abstract’ might be code, here, for ‘distancing,’ for occupying positions somewhere between the ironic and the dispossessed. Often Bennett’s subjects are shown to be far away from their origins, their pasts as distant as they are multifariously obscured by the present. As Grant alludes to, distance can be freedom as well as tyranny; to live abstractedly can be to live with two or more inconsistent ideas, to hitch contradiction to human nature.

All this vacillating intellectualism in Selected Writings exemplifies Bennett’s self-confessed perfectionism powered by doubt. As an artist who at times may have personified Michel Foucault’s disciplinary accounts of history, creativity and identity, it is surprising that, after declaring in 1992 a wish ‘to say nothing about my work,’ how long it actually took him to stop trying to control its interpretation.[25] Surely, he of all people was aware of how writing is no less a ‘performance’ than speaking. Yet, true to his contradictions, Bennett continued to promote his specific intentions many years after committing to a period of silence.

For a publication purporting to showcase the artist’s voice, this ‘will-to-silence’ is a productive tension. In a YouTube discussion with the editors hosted by Power Publications, Riley Walsh stated that he thought it was now ‘time for Bennett’s own voice to really be heard much more strongly’ than it has been in the past.[26] We shouldn’t forget, though, just how prominent Bennett’s words have been, especially in comparison with some of his peers (‘The collected writings of Tracey Moffatt’ I cannot see happening). The artist’s first monograph, The Art of Gordon Bennett (1996), was co-authored by Bennett and Ian McLean, and was prescient in its portrayal of the artist-historian relationship as collaborative, and art history as ‘platform giving’ as much as ‘positioning.’ It anticipated a trend, most detectible in the Phaidon series of monographs, of art publications providing more platforms to artists through artist writings, interviews and editorial selections. To this end, rather than seeing Goddard and Riley Walsh’s publication as liberating Bennett from, say, McLean’s art-historical grip, it reminds readers just how central the artist’s voice was to his work’s success.

'Please don’t quote any of this scribble,’ Bennett writes in a 1995 letter to the Swiss curator Lucienne Fontannaz.[27] Likely self-effacing and tongue-in-cheek, it still gets me thinking that he would have hated having his work-in-progress ponderings, doubts and foibles all miscellaneously laid bare like this. For this reason, against expectations, Gordon Bennett: Selected Writings ends up foregrounding how a commitment to an artist’s words is not the same thing as pandering to their intentions. It’s a critical sentiment I dare say Bennett would have respected.

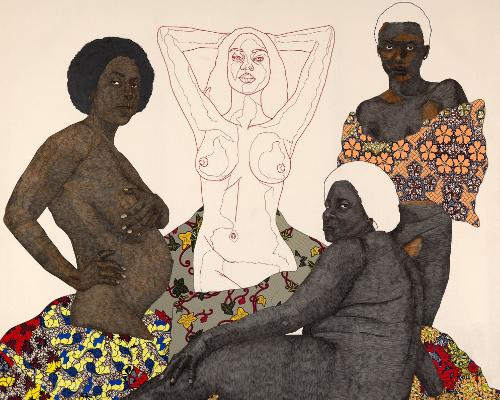

Estate of Gordon Bennett.

Footnotes

- ^ Angela Goddard and Tim Riley Walsh (eds.), Gordon Bennett: Selected Writings (Brisbane/Sydney: Griffith University Art Museum and Power Publications, 2021), 97.

- ^ Josh Milani quoted by Jeremy Eccles, “Book Review: Unfinished Business: The Art of Gordon Bennett,” Art Almanac (May 2021), 26.

- ^ Djon Mundine, “White Face/Blak Mask,” Artlink, 25:3 (2005), 18.

- ^ Terry Smith, “Australia’s Anxiety Again: Remembering the Art of Gordon Bennett,” Eyeline, 82 (2015), 40-52.

- ^ Adrian Piper, “Some thoughts on the Political Character of this Situation,” Institutional Critique: An Anthology of Artist’s Writings (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2009 [1983]), 243.

- ^ Smith, 44.

- ^ Goddard and Riley Walsh, 44.

- ^ Goddard and Riley Walsh, 74.

- ^ Hal Foster, Bad New Days: Art, Criticism, Emergency (London: Verso, 2015): 33.

- ^ Goddard and Riley Walsh, 133.

- ^ Goddard and Riley Walsh, 82.

- ^ Goddard and Riley Walsh, 98.

- ^ Goddard and Riley Walsh, 97.

- ^ Goddard and Riley Walsh, 106.

- ^ Goddard and Riley Walsh, 30-31.

- ^ Goddard and Riley Walsh, 135, 54.

- ^ Goddard and Riley Walsh, 54.

- ^ Stan Grant, On Identity (Sydney: Hachette Australia. 2019): 16.

- ^ Grant, 22, 85-86.

- ^ Goddard and Riley Walsh, 37.

- ^ Goddard and Riley Walsh, 135.

- ^ Goddard and Riley Walsh, 51.

- ^ Goddard and Riley Walsh, 105.

- ^ Goddard and Riley Walsh, 136.

- ^ Goddard and Riley Walsh, 82.

- ^ Tim Riley Walsh, “Artists after Gordon Bennett: Speaking through Text / Corresponding with the Past,” Power Institute, 14 October 2021, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dZwSGJmzM-M accessed 22 January 2022.

- ^ Goddard and Riley Walsh, 97.