‘I defy any lover of painting to love a picture as much as a fetishist loves a shoe.’[1]

In 1930, Georges Bataille made this provocation in response to the artistic commercialisation of his surrealist contemporaries. Art’s function and purpose was already being destabilised in the wake of Duchamp, but the question of the ‘fetishised object’, be it artwork or shoe, is always up for reassessment once it is repurposed. As Denis Hollier elaborates in his essay on Bataille and fetishism, to love an artwork as a fetishist loves a shoe is a matter of its pure use-value, or ‘The Use-Value of the Impossible.’[2] It is a matter of the art lover’s obsessive, irremovable closeness to the object. Here, Bataille’s conception of use-value takes on a paradoxically useless existence. For the fetishist, the use-value of the shoe begins ‘the moment it stops working, when it no longer serves to walk.’[3] The use-value of the fetishist’s object is entirely separate from its typical, productive use. It is spent in a moment of encounter where, for a sacrificial instant, no separation between ‘subject’ and ‘object’ remains, only the communication of sumptuous material. In the theatres of contemporary art, is it possible that an art lover could waste away before art as a fetishist does a shoe? Can any exhibition deliver such evidence? In the autumn of 2021, Out of Place at the Drill Hall Gallery approached the art lover’s fetishist gaze. Here, the apparatus of everyday use transforms into the ‘useless’ forms of art.

Meticulously curated by Oscar Capezio, the artists selected for Out of Place set the tone for an exhibition that approached notions of ‘place’ beyond the confinements of locality and generational lines. This included a broad style of ‘site specificity’ wherein the conventional definition of ‘site’ is expanded. Here, ‘site’ could refer to a scene on a postcard, the furniture of a classroom, or a particular footpath chanced upon by the artist. This moment of encounter was key to Capezio’s curatorial line, where the selected works dislocate the fixity of place in a complex weave of internal and external referents.

Opening with Thomas Demand’s Daily photographs (2008-2011) the central gallery was occupied by recent works by Fiona Connor, as well as Hany Armanious’ inkjet wall-print Stereotypes (2018) and Dale Harding’s monochrome and glass pieces. The left wing of the gallery took on the neon-pop atmosphere of Bub’s Hello Heimo (2017) alongside Janet Burchill and Jennifer McCamley’s SAFE (2005), while the right wing was dedicated to the land art of Boyle Family, and Igor and Svetlana Kopystiansky. As I looked at the art, I was drawn to the gaze of the flaneur, or the anthropologist, that is also the gaze of the aesthetically trained artist. I pictured an artist traversing their landscape with an obsessive eye, and a ragpicker’s talent, as readymades and colour-fields leap from an encounter with a painter’s studio wall (Armanious), a playground (Jordan-Lang), or the door of a local venue (Connor). Whether or not this process runs true, the artwork resonates with this imagination as it imprints the residue of the site.

Throughout the exhibition catalogue, the question of ‘the fetish’ is raised with an understandably cautionary tone as the danger of a Marxist-Freudian ‘fetishisation’ haunts the academy. Here, the experience of the fetish is usually something to be avoided at all costs; it is a crude power relation wherein something is made subordinate to someone. However, I was struck by an expression of ‘the fetish’ different to that of an objectified sublimation (Freud) or commodification (Marx). In Out of Place, the work’s relation to the site marks the moment of Bataille’s fetishist encounter where an object no longer serves its intended function, but the fixations of the art lover. That is, the work in Out of Place traces the artist’s encounter with an intriguing form, sliced from everyday life and placed in the gallery. It marks a point of destruction, and communication, of which the final ‘work’ can only show a trace; forever incomplete and displaced. By looking to a selection of artworks from Out of Place, this trace may be glimpsed vicariously.

In the left wing of the gallery, Burchill and McCamley’s contextually loaded Freiland series depicts an assortment of objects and furniture-arrangements from a Turkish meeting place where the Berlin wall once stood. The work effects a deliberate failure of documentary photography in which a potentially crude politick of place is side-tracked by a focus on the immigrant site’s minutia.[4] The compulsive taste of the fetishist artist comes through in the way Burchill and McCamley describe their encounter with the site: ‘[We] were struck by both the art tropes so evident in it (from Bauhaus to a down market John Armleder) and its beauty as a sculpture/assemblage.’[5] This fetishist reading of art into the everyday (as opposed to putting the everyday into art) demonstrates the closeness of the artist to the objects that entice them, and the lengths to which their interest consumes their environment. This perspective recurs throughout the exhibition, signalled at the gallery’s entrance with Bonita Bub’s The Donut (2013-2020).

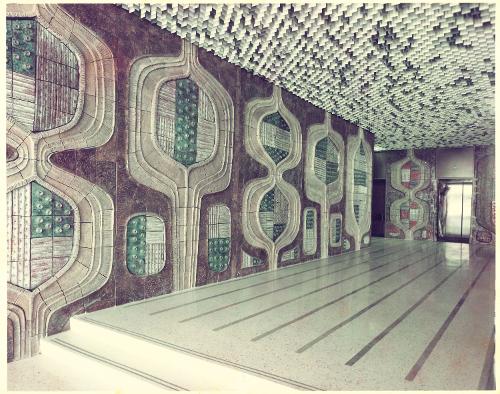

Made from stainless steel and high-density paper fibre board, Bub modelled her structure on a postcard depicting a drinking bar designed by modernist architect Werner Düttmann. She undertook this analysis in great detail, gazing deep into the photograph to extract the internal scale of the bar’s components. Such dedication signals a kind of devotion, an intense desire to be as close to the object as possible. Bub’s bar was used for wine tastings throughout the exhibition, returned to a position of functional support. However, as an artwork made from a chance encounter with a postcard, it expresses the fetishist’s drive toward the object. The tension between its use as a drinking bar, and the use-value of the image’s initial captivation, is consistent with a sense of displacement and contradiction throughout the exhibition.

Fiona Connor’s Untitled #37 (2020) from her Classroom Furniture series is a recreation of a white pinboard, a creamy monochrome with historical appeal to the modernist art lover. On closer inspection, the board’s former use is revealed by engravings on its cork surface. Its precise location is given: 24700 McBean Pkwy, Valencia, CA91355. Connor’s work hung adjacent to Jasper Jordan-Lang’s PG-84 (Poseidon) (2020). This resin cast of playground equipment embodies a similar recollection of the site, painted to mimic the Brunswick Green heritage pantone of the original. This decision tethers the works to a particular place. However, its façade is chipped and dirtied like an artefact belonging to a long-lost civilisation. Thus, Jordan-Lang highlights the object’s potential for decay that is also its potential for rebirth. Through a fetishists gaze, a painted-over pinboard transforms a classroom into a gallery, and a playground is inspected as an museological fragment.

Casting was also central to the left wing of the gallery, with Boyle Family’s slabs of earth from 1976 to 1979. Rendered in painted resin, these illusionistic forms replicate an area of land given by a set of coordinates. Here, land is shown for the sake of its minute textures, from the cobblestones of Lorry Park to a dried-up watercourse in the Tanami desert. Again, the fanatic exactitude with which Boyle Family undertake the process of replication speaks to the moment of encounter between artist and site. The psyche of the fetishist ties with Boyle Family’s psychedelic roots, where surface details are open to subjective, hallucinatory vision. Alongside their large, brown slices of trompe l’oeil earth hung Jordan-Lang’s pale, concrete relief Y2k12 (2018). This cast section of suburban sidewalk captures an area defaced with a name, heart, and date; a moment destined for perpetuity with the poignancy of a lover’s scrawl.

While many of the works shown in Out of Place are large in scale, they deal with the minutia of the site, like a fetishist wandering the streets, searching for a long-lost shoe. From painting and casting to video art and various modes of photography, the works shared an obsessive attention to detail on the part of the artist and their painstaking approach to mimicry. The artist’s devotion to the history of art, particularly that of modernism, appeared across the gallery through stylistic gestures and contextual information. Thus, in terms of the exhibition’s position in the history of site-specificity and public art, it revises any populist residue these terms may still carry. Here, site-specificity is not serving a denial of white-walls, or institutional critique, but rather continues a modernist ethos of art for art’s sake to the point of its feverish consumption of the site. Moreover, the exhibition denies any fixed notion of place; there is no ‘authentic’ experience of locality, only the experience of its traversal. As Bataille’s fetishist collapses time and space in a moment of consumption, Out of Place traces these captivating instances where selves are devoted to objects, and objects come alive as sites for transformation.

Footnotes

- ^ Georges Bataille, “The Modern Spirit and the Play of Transpositions,” in Undercover Surrealism, eds. Dawn Adès and Simon Baker, (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2006), 242.

- ^ Denis Hollier, “The Use-Value of the Impossible,” trans. Liesl Ollman, October 60 (1992): 3-24.

- ^ Hollier, 13.

- ^ Helen Ennis, “On Janet Burchill and Jennifer McCamley’s Freiland series” in Out of Place, (Canberra: Drill Hall Gallery, 2020), 24.

- ^ Ennis, 25.