.jpg)

On April 29, I choose not to celebrate the arrival of colonial invaders and the dispossession of our land. Instead I want to acknowledge the original inhabitants whose lives were changed forever on this day [in 1770], as well as affirm our survival, and reiterate that sovereignty was never ceded.

Reko Rennie[1]

Marking the 250th anniversary of colonial first contact, various cultural measures were planned throughout 2020 to mark—in public—the event of Cook’s Endeavour landing on the east coast from a First Nations perspective through artistic programming and actions from the Australian Government, including an upgrade to Kamay Botany Bay. In the context of this thinking and planning around the ‘anniversary’, Kamilaroi artist Reko Rennie was commissioned by Carriageworks in Sydney to create a responsive work at the signage structure at the Wilson Street entrance to the precinct. The outcome, REMEMBER ME—a monumental, illuminated text work—was planned to launch within the second of Wesley Enoch’s three iterations of Sydney Festival. However, extreme air pollution caused by the bushfire crisis that summer caused delays to Rennie’s installation and its intended launch on Invasion Day on 26 January was thwarted.

As it happened, the work was finished soon after and publicly launched on the fateful date of 29 April. Not with an opening event, but via a digital marketing strategy, part of the ‘new normal’ of how we quickly learnt to gather and mark occasions online during that other crisis: COVID-19. Conceptualised, developed and delivered between bushfires and lockdown, the visceral and politically charged sentiment of Rennie’s work took on new meaning as Carriageworks entered a 10-week voluntary administration process from 4 May 2020, brought about by loss of income due to closures related to COVID-19. As Carriageworks slept, I was at home in lockdown like everyone else glued to Instagram dominated by images of REMEMBER ME in a flood of support for Carriageworks.

Some fourteen months later, at the time of writing, I’m working from home again. The lockdown in Sydney is now four-weeks-and-counting, with other areas of the country experiencing health orders and border closures as the coronavirus’s Delta strain aggressively spreads within the community. Thinking through art’s relationship to public life and civic space while inside, day after day, has never felt more urgent. Once again, museums and galleries are temporarily closed, creating havoc for artists, exhibition schedules, and programming teams across the sector. And yet, in the bubble of my neighbourhood, the art still ‘open’ (beyond the digital public sphere of social media and online gallery programming) is the public art trail of my lockdown walks. Fiona Foley’s Bibles and Bullets (2008) in Redfern Park[2] and Nell’s Eveleigh Treehouse (2020) at South Eveleigh[3] are two works I frequently visit. Created for tactile interaction and play, they are now temporarily labelled with public health safety signage, cautioning the community of the risk of viral transmission. It gives David Cross’s closing essay on art, play and public space an unintended irony.

In its four-decade history, Artlink has been a vigorous contributor to discourse on the development of public art in Australia, its first issue on the theme in 1989 sporting Bert Flugelman’s Lawrence Hargrave memorial, Winged Figure (1987) being airlifted by helicopter, (before being plonked into place in Wollongong), as its cover image. While understandably dated in its aesthetic, conceptual and political considerations—not to mention scant reference to First Nations content, so typical of the time—what still rings true is the notion of public art as a health-related issue. Among the more notable contributions was an extracted paper by Ilona Kickbusch, then Director of the European Office of the World Health Organisation (WHO). Kickbusch refers to WHO’s definition of health ‘not as the absence of disease but an active process that is created in the daily interaction between individuals, their society and the environment.’[4] In the same issue, Australian architectural and urban critic Kim Dovey identified the seven properties that define healthy places: cohesion, vitality, transparency, identity, dynamism, continuity, and democracy.[5]

Almost a decade later, in a second issue devoted to public art in 1998, founding editor Stephanie Britton reflects how enough time had passed for some debates in this space to be dated while others rage on. One remark she makes remains perennial: ‘the act of putting an artwork into the public arena has become ever more a theatre of conflict, misunderstanding and a mismatch of expectations to the parties involved’.[6] Today, much of that ‘theatre of conflict’ is playing out in the contested dynamics of decolonisation and public truth-telling.

By 2010, Britton’s next issue on the topic included an essay length editorial that canvassed the developments in the field in Australia and internationally, with a critique on how public-ness had shifted too far towards private profit-making interests, leaving public art poorly integrated into city planning and placemaking strategies. Instead, it is added as an afterthought ‘to create visual distraction from a woeful lack of planning for liveability.’[7] Britton refers to the increasing role played by festivals (as ritual-marking traditions hailing from ancient times) in transforming public space through artistic interventions, despite their periodic and transient time signatures.

The postponement and cancellation of one festival after another due to COVID-19 in the last year has been a devastating blow for our arts and cultural sector, its communities, and audiences. NIRIN, the 22nd Biennale of Sydney (2020), imagined as an extensive network of socially interactive artistic actions was a notable casualty. Similarly, the anticipated RISING festival in Naarm/Melbourne, co-directed by Hannah Fox and Gideon Obarzanek faces increasingly familiar challenges: according to Fox, ‘public ritual and public space’ were key concepts for its development with an emphasis on place and ephemerality informing a collaborative and artist-led program.[8] The sad irony lies in how such work about ephemerality becomes subject to unintentionally transient programming, as our efforts melt into air. If ‘unprecedented’ was the buzz word of 2020, ‘it is what it is’ has become the 2021 equivalent to Australian vernacular once quipped with a shoulder shrug: ‘she’ll be right mate…’ But is it?

In January 2020, the Australian Centre for Contemporary Art (ACCA) announced Who’s Afraid of Public Space?—the third in their Big Picture exhibition series, following Sovereignty (2016-17) and Unfinished Business: Perspectives on art and feminism (2017-18). Developed over a two-year period with a diverse curatorium, Who’s Afraid of Public Space? includes symposiums, podcasts, public programs, on-and-off-site exhibitions with various institutional and corporate partners. When the first off-site project launched on 3 August 2020—a digital billboard located in St Kilda by Barkindji artist Kent Morris called Never alone—Melbourne was well into its 112-day lockdown. Riffing on Barbara Kruger’s postmodern pastiche of bold text and imagery to suggest and subvert the codes of advertising, Morris Indigenises the built urban environment by reflecting on Country, time and history during the loneliness and isolation of lockdown: ‘We have a remembered past, an anxious present and an uncertain future,’ says Morris.[9] Such sentiments are echoed in Rennie’s REMEMBER ME.

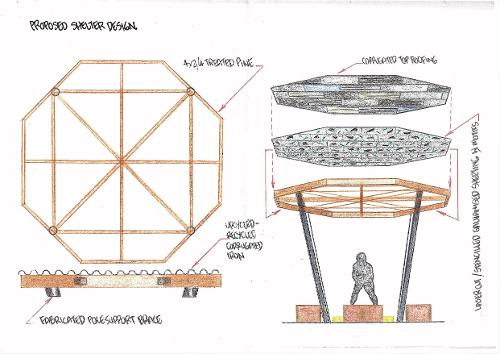

This issue of Artlink includes three conversations on public space, place and Country from diverse First Nations perspectives. Positioned as pillars, the conversations animate these pages with first-person accounts of existing or groundbreaking work in train. Up front, ACCA’s Max Delany leads a conversation with N'arweet Carolyn Briggs AM and Sarah Lynn Rees, who are developing Ngargee Djeembana for Who’s Afraid of Public Space? Their conversation unpacks the idea of Indigenous knowledge of place (Yulendj), and how architecture must be redefined ‘so that it meets the needs of First Peoples on their land, and supports their health and wellbeing’.

Aligning with Richard Bell’s survey at the Museum of Contemporary Art is a conversation between Bell, Clothilde Bullen, Ghillar Michael Anderson, Jenny Munro and Bronwyn Penrith, which candidly recounts the history of Aboriginal activism leading to the formation of the Aboriginal Tent Embassy in 1972 and Bell’s iconic Embassy installations. The third discussion between Genevieve Grieves and Amy Spiers, expands on an ACCA symposium on counter-monuments, never more pressing a topic than in times of toppled statuary.

Dispersed between each of these pillars are articles covering diverse approaches to and thinking around art in public. Further consideration to monuments is given by Wesley Enoch and Gerry Bobsien who turn their attention to memorials in the Hunter region for legendary Aboriginal boxers, Les Darcy and Dave Sands. Through major public artworks by Daniel Boyd and Yhonnie Scarce, Erin Vink considers First Nations memorials through the colonial frame of the museum. Aarna Fitzgerald Hanley contemplates how non-Indigenous artists Elizabeth Day and Gabriella Hirst create works about and on land, by negotiating the institutional impacts of colonisation.

Sasha Grbich looks at queer monuments through various artists and projects, including the Bondi Memorial Project—a tribute to gay male victims of hate crimes in the area. The queering of public space continues in Jessie Boylan’s coverage of activist pranksters, the Department of Homo Affairs. In a quieter neck of the woods, Fiona Kelly McGregor’s piece on Helen Grace delves into the archive of Amazon Acres, an experimental, feminist utopia/dystopia.

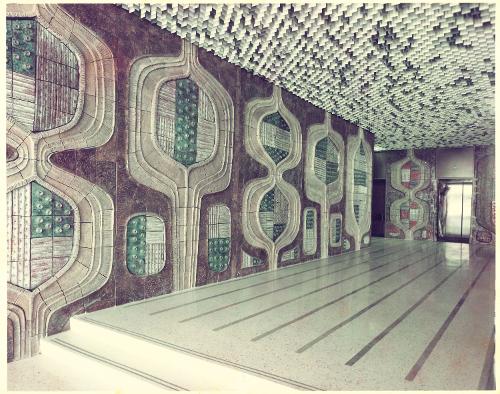

Elsewhere in the archive, Vanessa Berry unearths the work of Vladimir Tichy, a ceramic muralist who had not previously been addressed in art historical terms. Similarly, street art is not regarded by the canon, yet through various examples, Jacqueline Millner considers it as ‘a latter-day recuperation of Realism’. Abigail Moncrieff heads to the regions to examine community-oriented initiatives that ‘don’t necessarily look like art at all’ in the relational work of the Kandos School of Cultural Adaptation. Likewise, transformative community practice cuts to the heart of Rayleen Forester’s survey of various artists and collectives working today.

By no means an exhaustive overview of practices staged in public places, or the thinking that fortifies it, this issue offers a broad view of the ways that artworks and artists operate in public, in past and present tense, with urgent consideration of our tenuous future. We won’t be inside forever.

Footnotes

- ^ Reko Rennie, REMEMBER ME, 2020. Commissioned by Carriageworks and curated by Beatrice Gralton and Daniel Mudie Cunningham https://carriageworks.com.au/journal/reko-rennie-remember-me/ Accessed 26 July 2021.

- ^ Fiona Foley, Bibles and Bullets, 2008. Commissioned by City of Sydney for Redfern Park. This playground work made for 3-7 year old children is an important example of Aboriginal public art activism, embedded with symbolic references to colonial genocide while also referencing former Paul Keating’s ‘Redfern Speech’. Keating’s address at this same park in 1992 acknowledged governmental responsibility for the traumatic consequences of colonisation.

- ^ Nell, Eveleigh Treehouse, 2019. Commissioned by Mirvac and curated by Daniel Mudie Cunningham, Carriageworks for South Eveleigh.

- ^ Ilona Kickbusch, “Health and the City”, Artlink 9, no. 2 (Winter, 1989): 22.

- ^ Kim Dovey, “Seven Properties of Healthy Places”, Artlink 9, no. 2 (Winter, 1989): 28-29.

- ^ Stephanie Britton, “Editorial: Going Public”, Artlink 18, no. 2 (June—August, 1998): 4.

- ^ Stephanie Britton, “Editorial: The Meandering River: slowing down and keeping going”, Artlink 30, no.3 (September, 2010): 15

- ^ Hannah Reich, “The cancellation of Rising festival is a loss for the Australian arts community and Melbourne”, ABC News, 9 June 2021 https://www.abc.net.au/news/2021-06-09/rising-festival-australian-arts-melbourne-covid-19-cancellation/100184504 Accessed 26 July 2021.

- ^ Kent Morris, Never alone, Australian Centre for Contemporary Art, https://acca.melbourne/kent-morris-never-alone/ Accessed 26 July 2021.