Violent dreams of development: A food bowl in the north‑west of Australia?

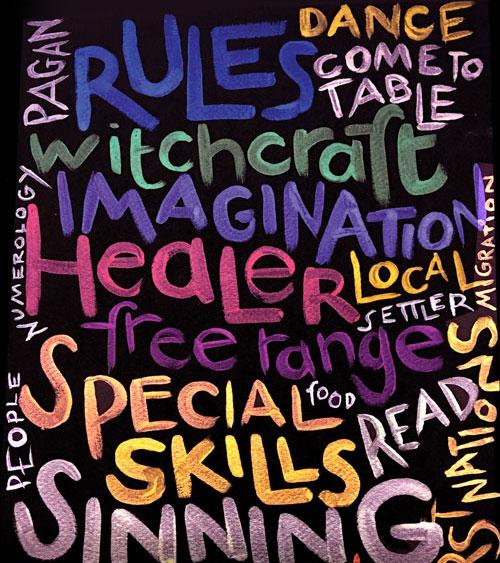

Do you know what lores I have had to learn while you play in everything they protect?… Do you understand that when you write the kangaroo the wallaby the bilby the bandicoot the cockatoo the blacksnake the waterlily the brush the bush the sapling the ghost gum that you are puppeting your hands through my ancestors?