Annie Pootoogook: Depicting Arctic modernity in contemporary Inuit art

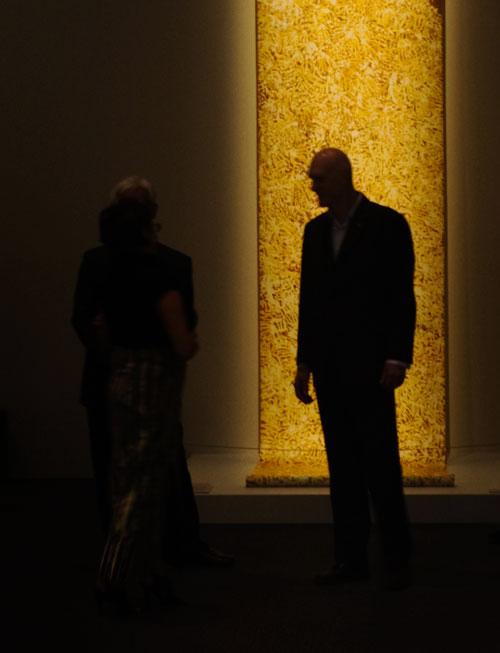

When graphic artist Annie Pootoogook passed away last year, there was an outpouring of public grief. Numerous articles were also published in the popular press, primarily focusing on her artistic career as a rising star whose success was marred by a descent into poverty and struggles with addiction. Pootoogook first gained national attention by winning the Sobey Award in 2006, a $50,000-dollar prize for a contemporary artist under forty years of age; a decade later she died, destitute and homeless, in Ottawa, Ontario.