Emily Kame Kngwarreye: The impossible modernist

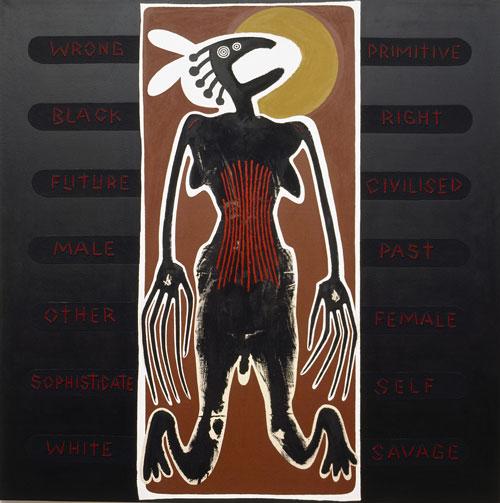

Art critic Robert Hughes made the assessment that Aboriginal art was the last great art movement of the twentieth century. It started at the Aboriginal community called Papunya, in which Aboriginal men had been painting on canvas for the outside market with great success since the 1980s. The Papunya art style, as it became known, sometimes compared to forms of Western modernism—from abstract expressionism to minimalism and even conceptual art—presented a comparison that was rarely taken literally, although some critics of the 1987 Dreamings exhibition in New York did wonder if the Aboriginal artists had been appropriating New York art. But when it came to the late paintings of Emily Kame Kngwarreye, critics really did start to question the relationship between modernism and Western Desert painting, ascribing to her the genius and expressive freedom associated with the masters of Western modernism.