Welcome to the “trans” issue as it is cryptically called (meaning across and beyond in Latin). The aim of this issue is transnational as much as transcultural: to explore relations between Indigenous contemporary artists across the world. So focused are we on the Australian context for Indigenous art that when it comes to aligning ourselves with international art, in both historic and contemporary contexts, we too often deprive ourselves of that defining peer‑to‑peer agency that permits new perspectives. When we step outside of this internal viewpoint to project ourselves internationally, as in the occasion of the representation of two high‑profile Indigenous artists in the national pavilions of Australia and Aotearoa New Zealand for the 57th Venice Biennale, this rite of passage clearly becomes apparent. It is one well‑served by Tracey Moffatt and Lisa Reihana, whose elegant visual narratives demonstrate a form of this trans‑aesthetic, appropriate to taking on Europe and the world.

Embodied in the cover detail from Moffatt’s nostalgic, noirish work from the series Passage, “Hell” is the roseate glow of new horizons, and new beginnings, a subject taken up by Djon Mundine in his poetic reflection on Moffatt’s oeuvre, that draws on her rich repertoire of film and literature. At a time when many people are stateless, and the world itself becoming borderless, defined by multiple crossings, this is a resonant image. As with Lisa Reihana, in Pursuit of Venus [Infected], so richly and elaborately peopled by encounters, is discussed by Nicholas Thomas in this issue in a thoughtful excavation of her source material, Les Sauvages de la Mer Pacifique (The Voyages of Captain Cook), the eighteenth-century French wallpaper in the collection of the National Gallery of Australia.

The inspiration for the focus of this issue arose out of my own encounter with the Multiple Modernisms project, a research cluster that met as a group in Johannesburg and Capetown in June 2016 to discuss the topic of Indigenous Global Modernisms. Heather Igliolorte from Nunatsiavut (via Quebec), Elizabeth Harney and Ruth Phillips, also from Canada, Jyotindra Jain from Mumbai, Nigerian‑born Chika Okeke‑Agulu (now based in Princeton) and Nicholas Thomas (an Australian based in Cambridge, UK),all contributing to this issue, were among the researchers attending. Ian McLean and I, comprising the Australian representation, embracing this trans concept in the air, saw the opportunity to generate the proposal for this issue of Artlink, also following on from some of the concerns raised by the 2015 Indigenous Global issue (edited by Daniel Browning and Djon Mundine) in “perceiving the distant”.

As McLean’s framing essay explains, it’s a hot zone of contact across genres, genders, generations, cultures and races. McLean takes the model of trans curation on in reference to the current and previous iterations of “La Biennale”, working the structural and historical rigour of Okwui Enwezor and the achievement of placing contemporary African art at the centre of global art. You might be amazed at the history and origins of the term transcultural with its many siblings and offspring—the transnational, transsexual, along with the various forms of cross‑cultural, intercultural, intracultural and multicultural forms of acculturation discussed across these pages.

The relatively new idea of multiple modernisms decentres the more familiar idea of a hegemonic Western modernism to focus on transcultural relations in all cultures including traditional Indigenous cultures in their engagements with modernity. The Multiple Modernisms mob are involved in a comparative transnational project largely concerning the multiple modernisms of Indigenous art across the former British colonies of Oceania, Africa, Asia and the Americas where they engage with artists as well as curators and other scholars. These scholars from Australia, Aotearoa New Zealand, India, Africa and Canada might be tooled in the universal protocols of contemporary scholarship, yet as if illustrating the transculturations they study present a diversity of writing styles and approaches to their respective Indigenous and national traditions to produce a cultural cacophany of voices.

Culture is more than art, and as evident in the essays in this issue, transculturation in Indigenous art reaches beyond purely art concerns to also address those of the transgenerational, transgender or transmigratory. Here, some “Elders” of the art and cultural industry write alongside the younger generation of Indigenous writers, such as Jessyca Hutchens, Jilda Andrews, Dan Taulapapa McMullin and Maddee Clark, interspersed with middle generation writers. In some cases the Elders and youngers exchange skills and knowledge across cultures, as evident in the essay by Una Rey and Nici Cumpston on the VR filmic work Collisions by internationally acclaimed filmmaker Lynette Wallworth working with the Martu. Jessyca Hutchens and Jilda Andrews, both young PhD candidates, traverse the intercultural and intergenerational domains where the past meets the present in the museum archive as part of the emerging archival turn in contemporary art. Jessyca Hutchens explores the re‑imaginings of the contemporary artist Christian Thompson in his consultations with the ancestors at the Pitt Rivers Museum at Oxford University, placing at its centre the figure of the artist. Jilda Andrews from the National Museum of Australia places the curator in the role of custodian and mediator of collections to re‑animate the archive with Indigenous values.

Wallworth’s Collisions similarly draws on archival footage from the Maralinga atomic testing and juxtaposes it with the personal and communal fallout in contemporary Martu communities. Rethinking histories through the lingering trauma and drama of post‑colonial spaces connects with the Moffatt’s practice of returning to the places and inspiration points to invoke loss, trauma and possible new beginnings. Reihana is doing the same thing with her continued reworking of the immersive spectacle of this dream of once‑exotic lands, made more poignant a negotiation in the return to Venice, as a centre of European art and design and trade between East and West.

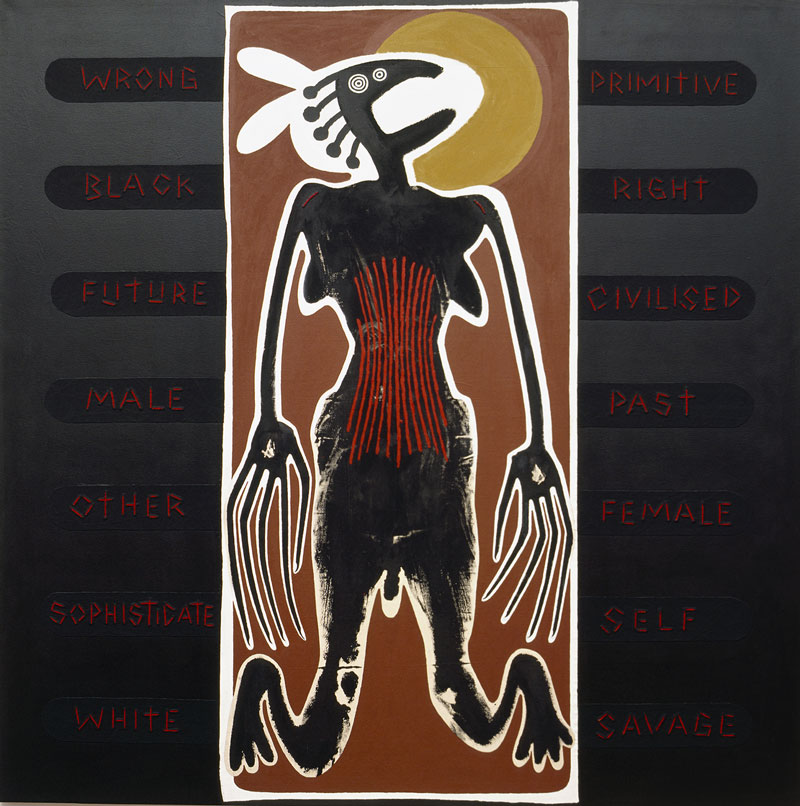

An insistence on grounding the trans in the culture of now is evident in Dan Taulapapa McMullin’s essayon working with Māori performance artist Rosanna Raymond, instigator of the SaVAge Klub, whose bare‑breasted breaking of QAGOMA’s protocols on nudity for APT8 was a highlight of this event, potentially to be revisited as she takes on the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. As such, Raymond joins the triumvirate of Antipodean power women featured in this issue, and like Maddee Clark, takes on feminist discourses, inflections of Indigenous contexts that challenge the idealist essentialist tendencies of transgender discourse.

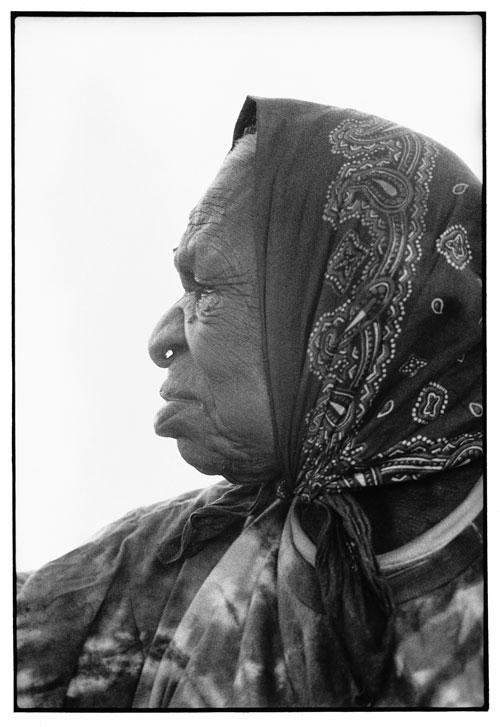

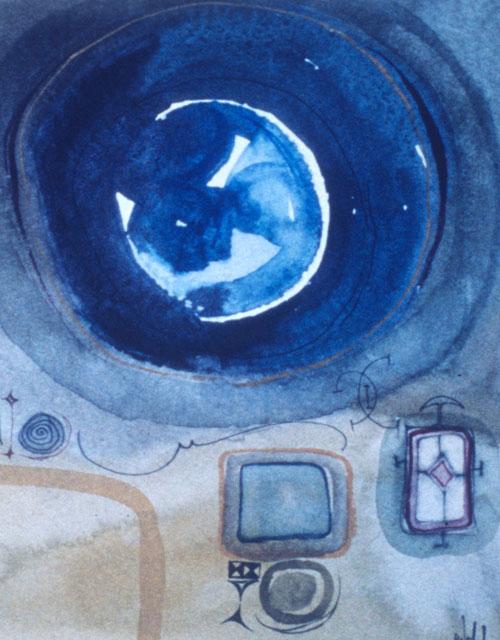

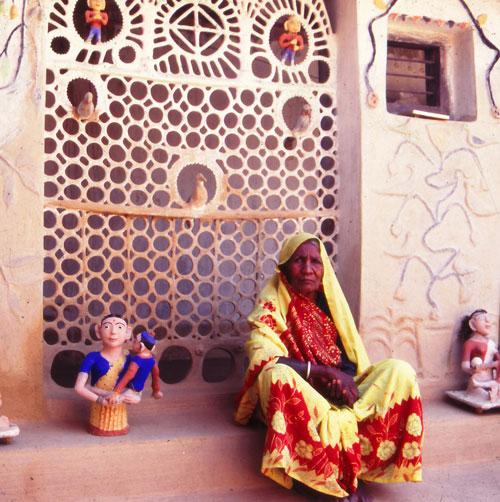

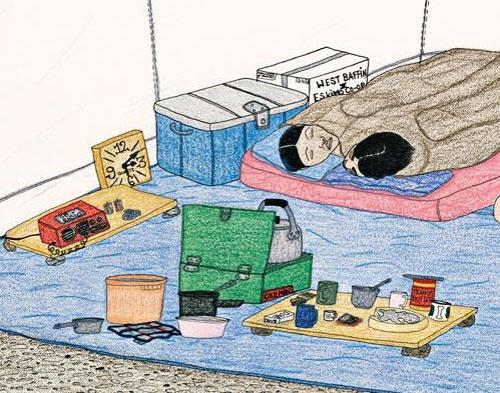

The intersection of tradition and modernity in the works of Indian folk artist Sonabai, Anmatyerre artist Emily Kame Kngwarreye, Inuit artist Annie Pootoogook and Nigerian artist Obiora Udechukwu with reference to Ghanian El Anatusui, work firmly in the transcultural domain. It is the impact of museological interventions that propelled these artists into new styles and new worlds of art.

As a collection of writings and artists profiled to reveal parallel histories, lingering traumas and opportunities arising out of postcolonial spaces, what is striking is the diversely connective presence of ideas across these pages. The intersection of the past in the present is part of this transcultural space. As our Elders say in different ways across the country “when you look behind you, you see the future in your footprints.” What also drives us on is spreading some form of empowerment to embrace artists as individuals working in communities, museums, universities and public life in whatever capacity and wherever they are located. As McLean argues, unlike its opposite, acculturation, transculturation is about the agency of local voices and their exchange with others in the larger globalisation of our era. You can never get the local out of the global.