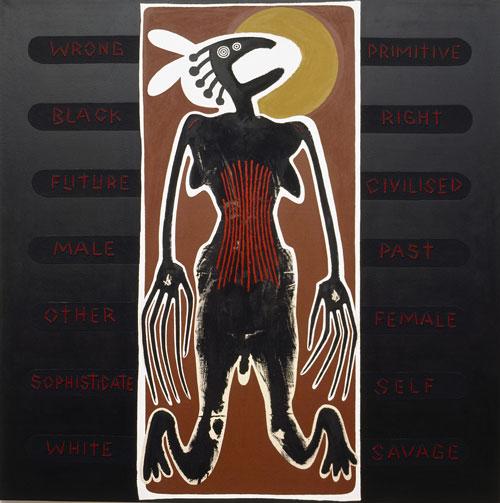

The Masque Ball of Tracey Moffatt

One of Tracey Moffatt’s lasting cinematographic memories, as she told me, is of films with harbour scenes, of working ports, rough workmen, the coming and going of exotic people, fogs, and foghorns. Tracey Moffatt’s photographic and film work commissioned for the Australian Pavilion in Venice responds to this landscape of cinematic time.