.jpg)

You can tell a great deal about a country by what it chooses to remember. One can tell even more by what a nation chooses to forget.[1]

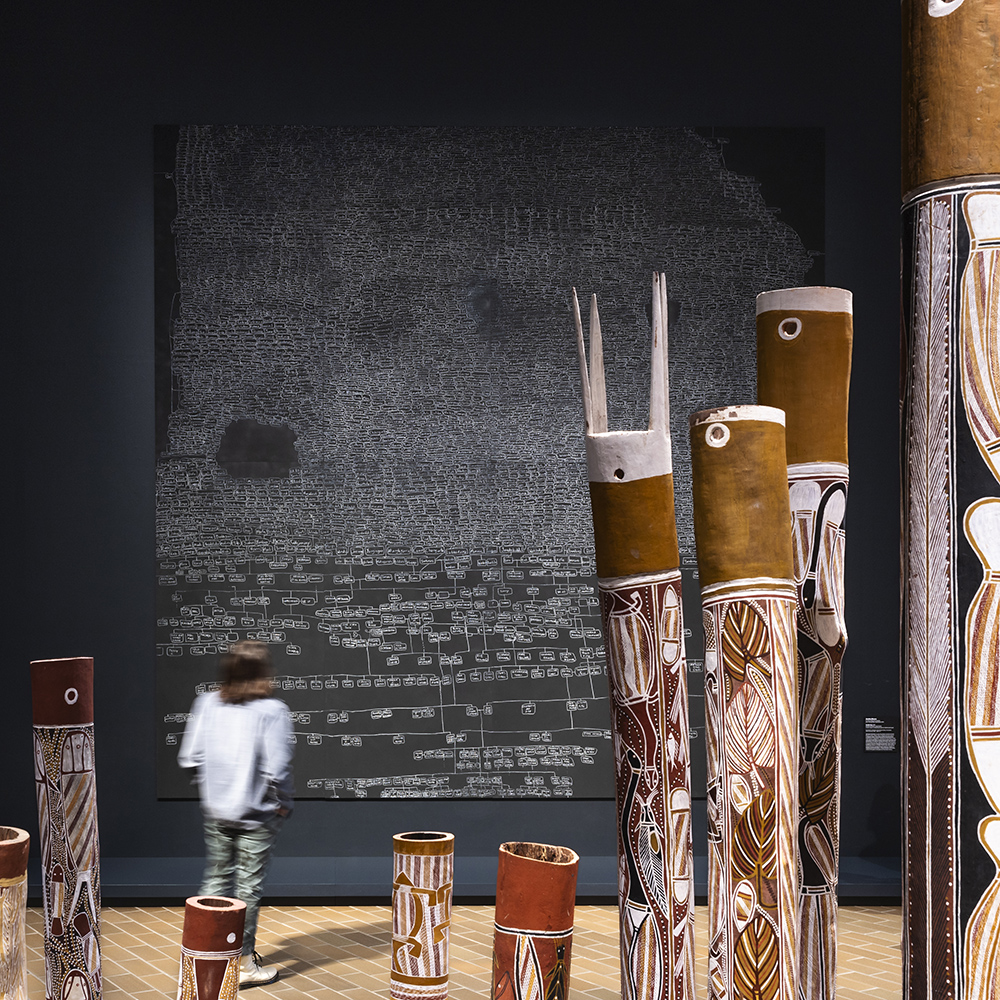

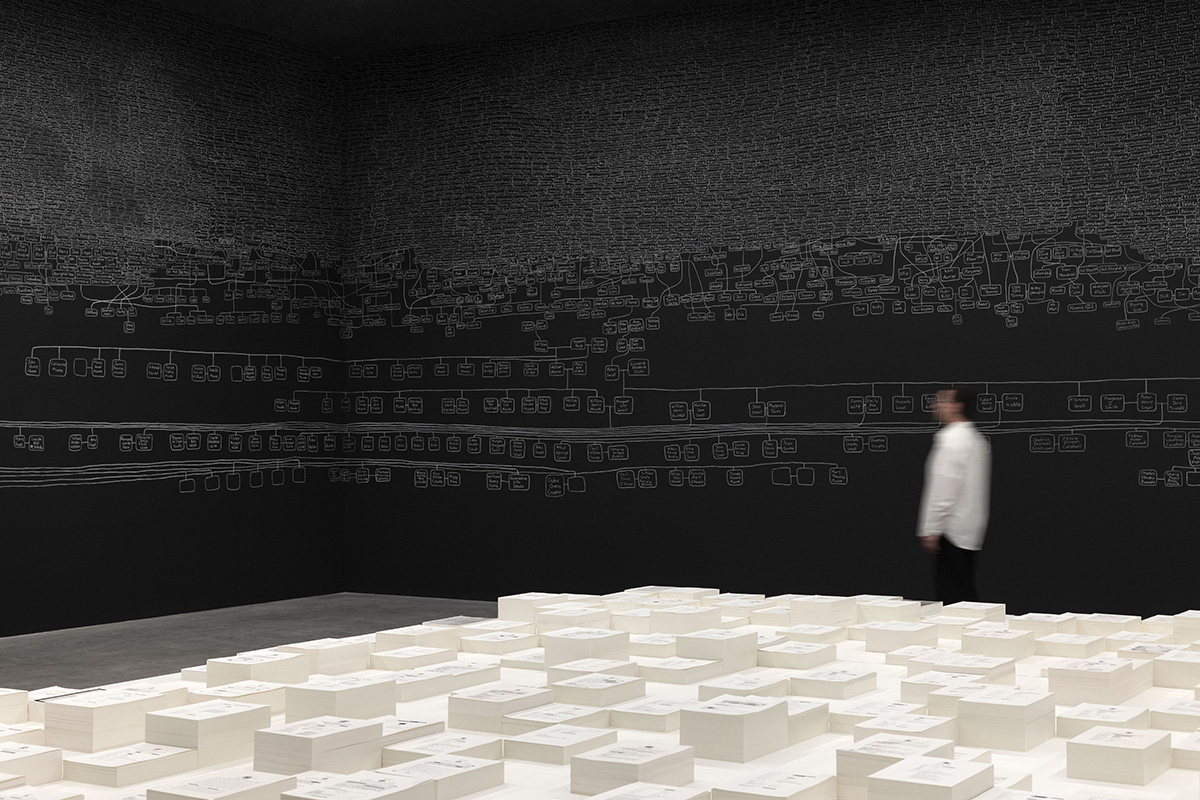

The words of Lonnie G. Bunch III, founding director of the National Museum of African American History and Culture are pointed, and no part of the globe is off the hook. The year 2024 has progressed through many twists and turns and curious historical moments, some more forgettable than others. This year is the bicentennial anniversary of the Declaration of Martial Law in the then-British penal colony of New South Wales that, in effect, turned all Aboriginal people into ‘outlaws’: outside the law, they were people who could be shot on suspicion and on sight. Colonial invaders took to this with relish. Unlike Australia’s 1988 bicentennial celebrations of the arrival of the first shipment of British prisoners that prompted millions of dollars on incredible numbers of national acclaim—performances, art exhibitions, writings and political orations—it would appear that we Aboriginal victims and survivors are the only ones to acknowledge this crime enacted in 1824 and to speak to and honour the dead and attempt to counsel ourselves. Artist Archie Moore’s words on his work currently being celebrated internationally, say as much: 'kith and kin is a memorial dedicated to every living thing that has ever lived, it is a space for quiet reflection on the past, the present and the future.'

Archie's kith and kin with family tree installation astounded the world this year by winning The Golden Lion Award for Best National Participation at the 60th Venice Biennale, the art world’s most preeminent event. I’d come to meet Archie some twenty years ago, and we’ve kept up conversations here and there, serious conversations, and picked up on each other’s particular research and obsessions, and our own forms of seeing the world. I’d really admired his view of the world, of searching out 'left of field sources', and I’ve seen a progression of exhibitions and artworks that have become more explicit, more complex and profound.

The near past.

In many country regions of Australia, you are told ‘there were no Aboriginal people living here’ or that ‘there are a few, but they’re not really, Aboriginal people (of mixed descent!)’. I think colonisation travelled through three moves or stages: at first cursory meetings, then, as the colonial intent becomes clear, resistance and violence ensues, and in the Australian context, an attempt at annihilation of the Indigenous population begins. This ‘move’ has been described heroically as ‘clearing the land’ or ‘dispersing’ the Indigenous populations. Then surviving Aboriginal populations, legally redefined, disempowered and displaced onto restricted lands (reservations), are given over to care by Christian missionaries to be re-educated and ‘civilized’ in the European model. No matter whatever the missionary, denomination, character, type or form, their aim, to the present day, is to break the intergenerational bond. And there are those Aboriginal people not legally allowed to live on reserves who lived in shanty towns on the fringes of ‘white Australian’ society. It was into this national history and oppressive, regional social wasteland that Archie Moore arrived, and where his story begins.

‘My blood is mixed … this mixture was not respected,’ the Native American character Nobody (Gary Farmer) tells William Blake (Johnny Depp) when asked what his totem is. The scene is from Jim Jarmusch’s film Dead Man (1995). It’s well documented that Archie found solace and inspiration in movies and music.

There is the reconstruction of Aboriginal identity and a rage that appears in nearly all Archie's artwork leading up to Venice in 2024. Archie Moore (Kamilaroi/Bigambul people) is of Aboriginal descent on his mother’s side and Scottish descent on his father’s. He was born in 1970 in Toowoomba hospital in regional south east Queensland and grew up and lived in Tara, among a shadow population struggling with definitions of identity and a lack of respect in a world of ‘dirt’ poor fringe families… poor white trash with a touch of Aboriginal [sic], described by Archie in conversation: ‘you could always tell if someone was home just by looking though the sizable holes in the walls.’ The tiny town of Tara, 171 kilometres west of Toowoomba, was also a place of tiny imaginations and outlooks, which Archie has described as

…an all-encompassing, stifling milieu … apart from the lack of resources or access to anything creative from outside the town—there was no art gallery, no cinema, no record store, no bookshop—people would not encourage you to do anything other than drink, fight and chase feral pigs.

Despite his jibes and sarcastic comments, it was in the intellectual desert of Tara that Archie discovered books and reading, and like many Aboriginal artists escaped into other people’s stories. However, from this regional ‘nowhere’ by the 1990s he made his way to art school and a booming, stimulating Aboriginal art scene in Brisbane. He was very clear on one thing: ‘I want to remain my own idiosyncratic self’. It was here in the mid-1990s that Wesley Enoch and Deborah Mailman created their Seven Stages of Indigenous Grieving: Dreaming, Invasion, Genocide, Protection, Assimilation, Self-determination and Reconciliation: of who we are, where we came from, what we experienced and what we must enact. The trail through the mist of Archie’s family forest is the awareness of this path, which leads to where we are now. And where to next, in reconciling this past?

Blackbird singing in the dead of night

Take these broken wings and learn to fly

All your life, you were only waiting

For this moment to arise [2]