I am not sure that I exist, actually. I am all the writers that I have read, all the people that I have met, all the women that I have loved; all the cities I have visited.

Jorge Luis Borges [1]

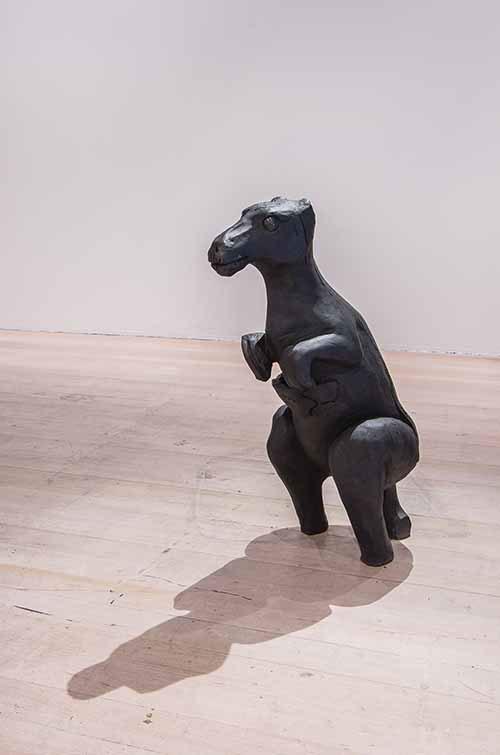

You are yourself – your own arrived at personality, and the position you fall into socially – and then, possibly, there is a setting in a larger social or language group (nation). The artist Karla Dickens gathers discarded material and cloth to construct and collage images and objects of people, times and emotional experiences, both sweet and bitter. Her ‘‘images’’ – her life and identity, like all of us – is constructed from fragments of other people’s lives.

Given the titular focus on International Indigeneity as a discussion point I wanted to move as broadly as possible around it. I didn’t want to be restricted to the ‘‘Commonwealth of Nations’’ list favoured by many Anglophile Australians. ‘‘But they’re all Chinese aren’t they?’’ a sophisticated Australian replied when I tried to discuss Indigenous ethnic minorities in China. Although there are some 600,000 Indigenous Canadians, there are nearly 40 million Indigenous Americans in the Caribbean and South America.

The arrival of the British to the continent we now call Australia was a continuous, persistent, death-by-a-thousand-cuts set of campaigns, whereby colonists attempted to exterminate Aboriginal people and render any survivors invisible and irrelevant. The colonial aim was to sever the generational bond. Genocide is not only the physical killing of a group it’s the imposition of conditions that aim at the breaking up of social and cultural, religious and linguistic bonds within the group to destroy its existence. To that end, Aboriginal people over the last 200 years were not only removed from their traditional lands (when not exterminated) but moved from one reserve (mission) to another, often in cattle trucks, at the convenience of government, property developers, and frugal churches, in the process splitting families, fracturing cultural practices and destroying languages. Maintaining a cultural memory and practice to maintain identity became incredibly difficult in these circumstances.

In the early 1980s the Commonwealth Government in Australia took up this definition of Aboriginal identity: ‘‘An Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander is a person of Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander descent who identifies as an Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander and is accepted as such by the community in which he or she lives’’. When the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission came into to being in 1989 it adopted this definition that acknowledges you may be of mixed descent (in fact, the majority of the population). In Australia, Aboriginal people fought against this certification of people to be officially defined as half-caste, quarter-caste and so on – terms that still exist in other post-colonial nations. We felt this way because it affected where we could live, where we could travel and work, and whom we could marry.

Even more seriously and cruelly, it also meant that we could be separated from our family and relatives. Other countries, such as Canada, the USA, and New Zealand, have different variations. The term half-caste created by white colonials in Australia insults our influence and presence, which outside of sport is clearly limited. The term métis used in Canada is cited in the constitution to refer to a distinct Indigenous group, mostly of French and Indigenous descent. In South America the term mestizo is used to refer to people of mixed descent. Maria Fernando Cardoso from Columbia, now an Australian resident, talks of this influence in her work and life in this issue. Although it may not have been a favourable term in the past, these people now make up the majority of the population and the influence of their cultural practices is significant across these societies.

In 1925, Sun Yat-sen stated that a modern Chinese identity is defined by descent, occupation, language, religion, and what he called folkways and traditions.[2] China, as a nation, officially recognises 56 ‘minority nations’ within their society. These groups may speak Mandarin but maintain their own languages, spiritual beliefs, and relations to land as well as their own rituals to spiritually and socially enrich the society and the land. To some extent they are tolerated as regional spectacle to boost internal tourism.

In this issue, Lindy Lee has written and discussed the dilemmas and struggles to create a form of Chinese diaspora personality and identity, living as an artist in Australia in the present time. Hers is a story of real pain and triumphant joy as she persisted to find a defined space and a fuller being that informs her identity.

Yuanyang, sometimes also called Ying Yong, is a popular beverage in Hong Kong, Guangdong and Singapore, made by mixing sweet milk, coffee and tea in the Hong Kong style. It was originally served hot or cold at dai pai dongs and cha chan tengs but it is now available in various types of restaurants. The name yuanyang, referring to mandarin ducks, is a symbol of conjugal love in Chinese culture. The birds usually appear in pairs but the male and female look very different. The same connotation of a pair of two unlike items is used to name this drink.

I was told by a curator in Singapore that yuanyang is a term also used to describe people of mixed descent. Back in Australia, an academic colleague told me the contemporary Aboriginal Walpiri word picaji, describing the yellow-brown colour produced when cow’s milk is added to tea or coffee, is used to describe people of mixed descent (half-castes) here.

With Catherine Croll, I took an exhibition to China called Yiban Yiban – Yellow Fellah in 2014, representing three artists of Aboriginal and Chinese descent: Sandra Hill, Gary Lee and Jason Wing. Southern China has a number of ‘minority nations’ societies. We conversed with several ‘‘minority nation’’ artist’s co-operatives in Kunmin, Chonqing and Guangzhou to exchange common ideas and expressions.

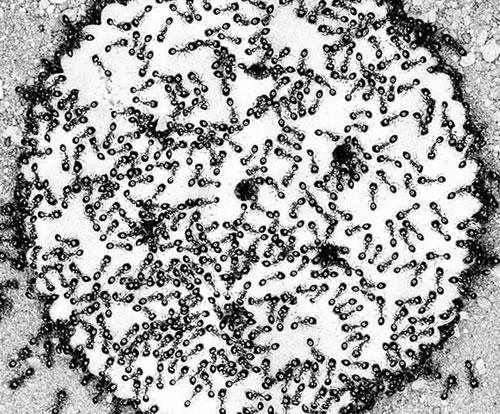

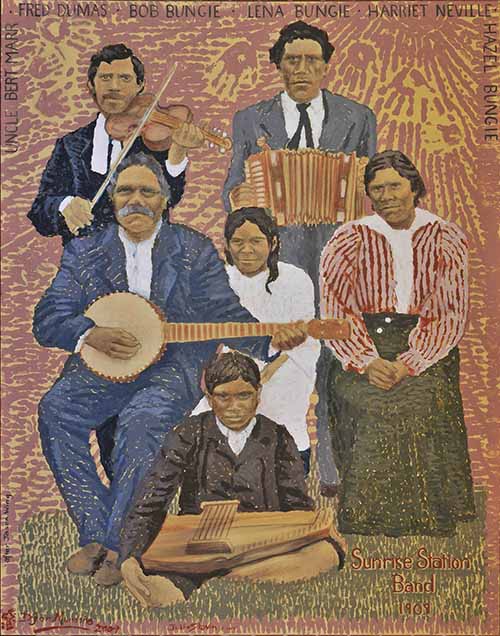

How do you announce your Aboriginal identity to make your presence visible? In 2009 I was asked to complete an artist residency for the Manning River Art Gallery at Taree. I’d carried a 1909 inspirational black and white photograph of an Aboriginal music band from Purfleet ‘‘mission’’ south of Taree on the mid north coast of NSW, for some years. Some one hundred years later, I worked with the descendants (family members) of this music group. I advertised for the heirs of this heritage to assist me in colouring this image, bringing the little-known but special human beings to life in a painting on canvas. I asked people to paint with their fingers and thumbs in a raw pointillist style that allowed children and people of all ages and skill levels to take part. The touching of their great-grand parents’ images was a form of grooming; looking at and caring for them as a form of haptic specificity helped to create a bond with them and their musical art practice. Over ten days, 38 family members collaborated together and the resultant painting is in the collection of the Manning River Gallery, with photos of participants in action.

As an Aboriginal artist, if you are invited to create art anywhere in Australia you have an ethical obligation to make contact with the local people. In 2014 I told the descendants of Peggy and Jimmy Lambert that if they were to make a claim to be the premier Aboriginal landowners they had to exhibit it – perform some ritual to indicate this, to make your presence visible. And I don’t mean being invited for a ‘‘token’’ payment to make a ‘‘token’’ appearance at some public events. Fellow artists Adam Hill and Jason Wing certainly follow this practice, as did local artist Tirikee Aleshia Lonsdale, born in nearby Mudgee, on this occasion to assert her presence through the creation of a low-relief sand sculpture Disambiguation.

For the 2015 Cementa Festival in the village of Kandos in the New South Wales Central Tablelands, I worked with the great-great-great-grandchildren of the Lamberts to paint their images onto the large external wall of the Kandos Museum (35 square metres). The finger painting by nearly 60 of their grandchildren was apt in another way, as it was the painting style of of the day in Jimmy and Peggy’s times, both referring to French pointillism and the Australian Heidelberg School of painting. Jimmy and Peggy were survivors of the Dabee Massacre of 1823 and so to bring their presence and that of the identity of their children back into the local history ‘‘warts and all’’ was very important. Several thousand visitors to the festival saw the work and quite a number of discussions on local history and family trees took place – the mural providing a mnemonic device.

I always thought it’d be better to be a fake somebody than a real nobody, Tom Ripley.

The Talented Mr Ripley (Dir. Anthony Minghella, 1999)

Borges’s statement at the beginning of this essay talked of who he was personally, not his public or professional mask, also to explore how he could escape his civic self. Everyone has a personal and a social identity. When I first went to Arnhem Land to work I described myself as a Bandjalung Aboriginal person in my application for the job. As I walked by local people would ask each other: is he Balanda (European) or Yolngu (Aboriginal)? No, he’s Aboriginal, they would laugh. In such communities people assess your personal self; your identity as an individual human being is as important as any-thing-else. It’s difficult to be an individual in today’s society and certainly difficult to be an artist. Identity is a much-discussed topic in the Australian contemporary art world.

Over 30 years ago I lived in a small traditional community where everyone in that society could recognize any-one-else in the society by their footprint. It’s a skill many people would give their right arm to have now. A lot of people wear shoes today and the number of people with that skill is half of what it was then. Thirty years ago children knew everyone in the population by their ‘‘skin’’ name and, by extension, their relationship to them, but that has similarly declined today. For most of my life people of mixed descent have fought to be seen as authentic Aboriginals and, to an extent, envied the apparent solid persona of those ‘‘full-blood’’ traditional people. But if we’re showing anxiety concerning our identity, character and status, think of the position of the former people. Do they know how to dance, do they really speak their language, can they make fire with sticks, and can they differentiate different species of animal, fish or plant? Not everyone is a David Gulpilil. A high teenage suicide rate across all Aboriginal societies indicates something is unstable.

Aboriginal artist Gordon Hookey once told me that as an art student the first thing he was taught was to look into the mirror and paint what you see, if you dare. In 2011 when I ran an Aboriginal art class in Goulburn Gaol I encountered resistance when I attempted to put this into practice. All participants were of mixed descent. It was nearly halfway through the course before they ventured into class. Several artists went straight into their portrait–identity, others really struggled and continually reworked their image over and over until nearly the end of the year. The results were as strong and individual identities as you could find. Cameras were forbidden as in court but it was an amazing process that I wished I could have recorded.

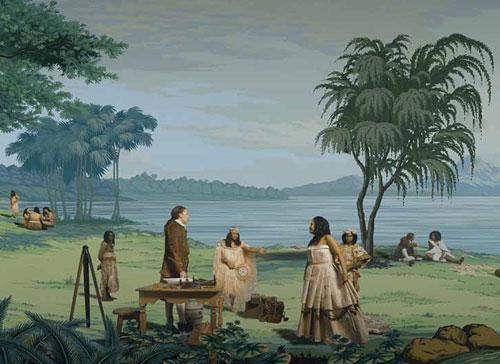

In 2015 I worked on the Bungaree’s Farm project with around a dozen artists to move them out of their comfort zone, to see and create new ideas and expressions. I was lucky to experience the amazing dramaturgy of Andrea James leading us through this process. To be Bungaree, to be in his shoes, each artist donned his colonial red coat and black hat and stated ‘‘I am Bungaree’’, ‘‘I am a hero’’ or however they were moved to describe him; in essence, being Bungaree, as every Aboriginal person standing in the face of colonial invasion. It moved many to tears to be in that moment, to be in that identity and feel the tension of his time.

I mean, who are you? You hate bloggers. You make fun of Twitter. You don’t even have a Facebook page. You’re the one who doesn’t exist.

Birdman (Dir. Alejandro G. Iñárritu, 2014)

So, in the present world, where are we? Throughout history, the wealthy have always expressed whatever they wanted, assumed whatever character they wanted, no matter the period in history or geographical place. We’ve progressed so far now we have an Aboriginal middle class. Some of these Aboriginal middle-class people wear their Aboriginality, as Brook Andrew allegedly once boasted, like a skin (a coating) only to position themselves further up the ladder in society. It would appear some hardly risk anything in this expression and wear it without risk of commitment to a responsibility. In the art world, where anything appears to be acceptable, Aboriginality for an artist can be an advantage, a card to play, in today’s marketplace.

The cover title of The Harvard Business Review in January was ‘‘The Problem With Authenticity – When it’s OK to fake it till you make it’’. When I first went to Arnhem Land, there was a belief that if you hadn’t been to a ceremony, you hadn’t experienced that thing, so you didn’t know about it. Kurt Vonnegut allegedly said that we are what we pretend to be so we must be careful about what we pretend to be. It could be thought that as Indigenous people are forced into assimilation and a shadow identity it creates a profound trauma on the soul. A great artist of Arnhem Land (now deceased) was continually troubled by the ever-encroaching Balanda (Europeans) into the world of the Yolngu people and in receiving Western treatment was diagnosed as being schizophrenic. In this condition your intellect is split from your affect – what you see and what you feel. R. D. Laing in the 1960s (I think) came to the conclusion that people in this state aren’t mentally challenged at all, but just struggling to maintain their presence, being and identity in a schizophrenic society – an impossible insane world.

Footnotes