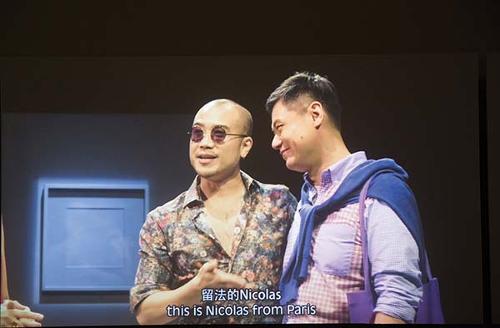

On 20 January 2012, on the request of the FBI, New Zealand police raided the Auckland mansion of Kim Dotcom, founder of file-sharing websites Megaupload and Megavideo, who stands accused by US authorities of copyright infringement, amongst other charges.

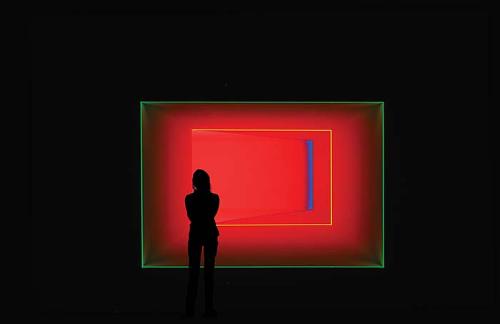

The fulcrum of the exhibition The Personal Effects of Kim Dotcom is the list of items taken in this raid, which is pinned to the gallery wall. Here are 110 items: including bank accounts, luxury cars, artworks, TVs, computer servers, video cameras, and domain names. Each of these items is represented as an A0 digital print, produced by Simon Denny in collaboration with designer David Bennewith. The gallery is also filled with 3D representations of the items: toy versions of the luxury cars, wooden sculptures of the TVs, real TVs, copies of the seized artworks, and similar versions of the jet ski and motorbike.

Much of Denny's recent work has circled around the evolving rhetoric and culture of the technology industry. The very title and focus of the exhibition, based on the fact that Denny simply downloaded the list of items off the Internet and Dotcom’s enthusiastic collusion with the media, highlights the issues as stake. The Personal Effects mines the Dotcom narrative for its morphing relationship between the physical and digital, and the increasing tendency of digital technologies to erode the borders of an original 'thing’ as well as the concept of ownership.

Predominant on the list of seized items are bank accounts from numerous countries and a series of domain names: Megastuff.co, Megaworld.com, Megaclicks.co etc. Denny flips these amorphous, digital, non-geo-located services into robust prints on ‘Premium Artist Canvas Polycotton’, anchoring them in space and time and on the most conventional of artists’ mediums.

Yet, as an exhibition project, The Personal Effects is politically mute. In public and media events Denny has been quick to distance himself from any opinion on Dotcom, his businesses, and recent foray into New Zealand politics. This is particularly marked given the timing of the exhibition, when many await the outcomes of the Trans-Pacific Partnership negotiations, a multilateral agreement which appears likely to extend New Zealand’s copyright term (life plus fifty years) and introduce stringent laws, serving the interests of multinational corporations, which will restrict the way citizens of the participating countries can use the Internet. Whilst Denny’s work exists in the increasingly contested space between original and copy, it maintains remarkably silent on the politics of policing intellectual property in the digital age.

In 2015 Denny will represent New Zealand at the Venice Biennale with Secret Power, a show that will address ‘the intersection of knowledge and geography in the post-Snowden world’. It will be intriguing to see how he neutralises or otherwise contends with another overtly politicised topic.