The Shanghai Biennale is something of a strange hybrid as an exhibition with international aspirations, yet one backed by a conservative and subtly xenophobic state. As such, the first couple of biennales were a process of testing the boundaries as China was beginning to open up to the outside world and contemporary art was and still is regarded with great suspicion as something potentially threatening to both political power and the moral sensibilities of 'the people'.

2014 seems to represent a break from this tradition with a curatorial team composed of respected art professionals from greater China (Cosmin Costinas from Para Site in Hong Kong, Freya Chou from Taiwan) and other curators from Berlin, Tel Aviv and China. The result is a tightly-curated exhibition, around a truly challenging theme Social Factory, which not only touches on some politically sensitive topics but taps into the zeitgeist of China by exploring how the social is produced - an interesting approach in a country no stranger to social engineering projects and where the private is inherently public because of the dominance of friend and family networks in the lives of individuals.

In his catalogue essay the chief curator Anselm Franke defines the scope of the biennale as not merely what happens on the factory floor but ‘the myriad ways in which actions, habits, and language produce effects, including effects on subjectivity, ways of perceiving, understanding, and relating to the world’. While this definition does not really offer a terribly clear goal, further reading of the essay highlights a number of key points which draw inspiration from Chinese history: the hegemony of scientific rationalism and the adage ‘seek truth from fact’ (a phrase employed strategically by Mao and Deng Xiaoping); the questioning of subjectivity (in relation to the Chinese woodcut movement); the resilience of certain traditional structures in the face of rapid change; the oneness of the cosmos put forth by Confucian thought and the moral wildness which Franke has transformed into a metaphor about ‘wild waters’ (though the works which visually reference water seem like a bit of a stretch); the instinct of humans to impose order on nature; and finally the transition of a society based on kinship into a society based on bureaucratic structures of collecting data and creating a concept of the social.

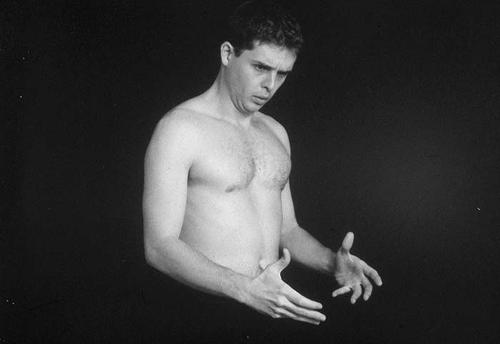

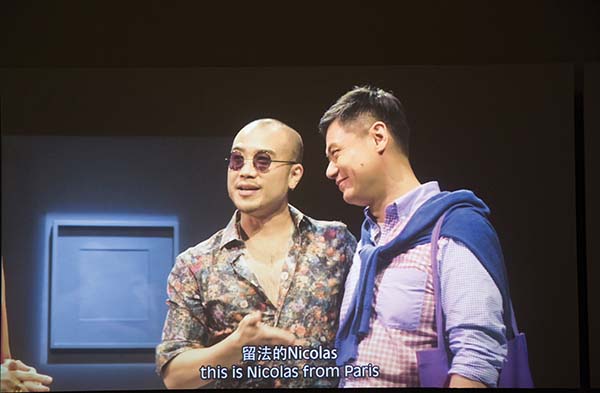

Franke has set forth an incredibly complex array of problems and, as such, the themes often speak louder than the individual works. That said, there were many pieces that both addressed a theme and were compelling in and of themselves. For instance Yu Cheng-ta’s Practicing LIVE (2014), a fascinating exploration of truth and fiction – a video and performance work in which Yu employed gallerists, curators, artists and collectors to play roles in a play about a family of art professionals. The humorous script is intercut by interviews with the actors about the experience of creating the play thus forcing the viewer to jump between various constructed realities.

Taking the construction of reality in a different direction, Susan Schüppli’s documentary-like Can the Sun Lie which talks of how Canada’s Inuit people have noticed that the sun is setting further west than in the past and posited the theory that the earth has rotated on its axis. The video goes on to examine how photography as a medium is now in the service of scientific rationalism – thus we see the state backed up by the scientific order colluding to shout down other voices. Edgar Arcenaux looks at the failure of the state – the end-game to our capitalist economy in The Algorithm Doesn’t Love You a multi-part installation which features his Gods of Detroit drawings of deformed human/alien hybrids juxtaposed with the words BKANS, PUILBC SIVEERS, EDCAITUON – a metaphor for how the pillars of society have become alien and misshapen.

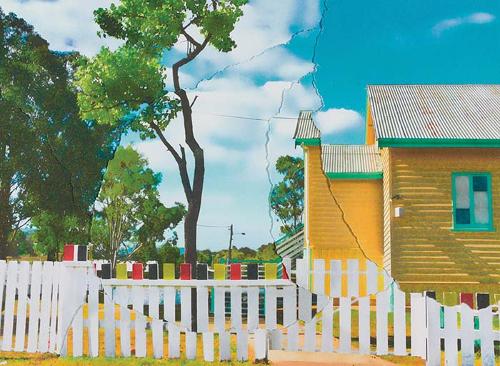

Hou Chun-Ming’s Asian Fathers series is part of a number of works that addresses societal pillars, in this case ‘The Asian Father’, and the way that in Taiwan’s post-martial law era ‘patriarchal fascism’ is on the decline but patriarchal structures underpinned by deep Confucian values still exist. Hou solicited memories in pictorial form via a questionnaire, created images from these sketches and then asked the participants to respond to them.

The 2014 Shanghai Biennale will be remembered as one which did not give up her secrets easily. There is little eye-candy for the crowds that now flock to the Power Station of Art (the foot traffic has brought vendors selling sweet potatoes and stinky tofu). But, also taking in the extensive film program, it’s a biennale that slowly draws out an engagement with profound ideas.