Anyone who has ever looked after a garden knows that water is life. The much-abused Murray River somehow keeps going and flowing. though not without controversy and uncertainty. The Same River Twice, curated by Melinda Rankin and Fulvia Mantelli over two sites - a country regional gallery and an inner-city experimental art space – refers to a saying by ancient pre-Socratic Greek philosopher Heraclitus 'no man steps in the same river twice because it's not the same river and he’s not the same man’.

Stepping into both openings was to experience the ongoing heritage of the original inhabitants of Murray River country. We were smoked with eucalyptus bark outside both shows and formally greeted, while inside the gallery in the city a long professional dance and didgeridoo performance by Taikurtinna, led by Uncle Steve Gadlabardi Goldsmith and his son Jamie, brought home a few truths. The opening speaker at Murray Bridge, John Kean, brought in more recent art history by walking the gathering through a number of past exhibitions about the Murray River held at Swan Hill, Tandanya, the Contemporary Art Centre of South Australia and the Art Gallery of South Australia, among other places, over the last twenty years.

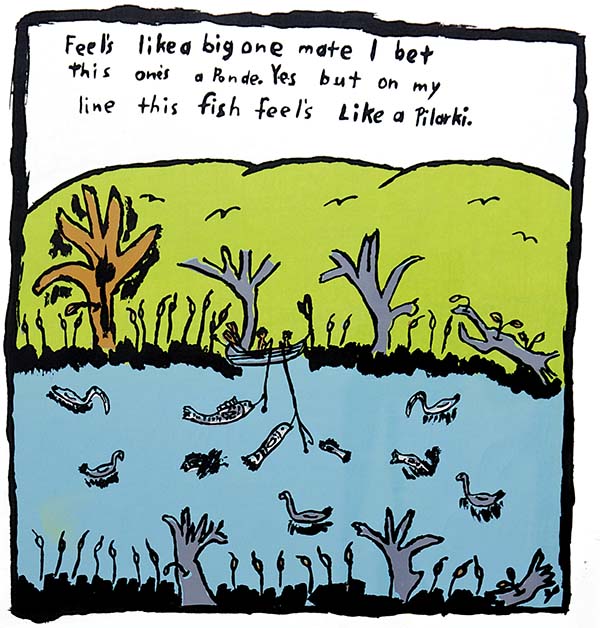

Making for a rich and detailed series of responses to the river, the exhibitions included commissioned and pre-existing art by Australian and Indigenous Australian artists: Ian Abdulla, Liz Butler, Nici Cumpston, Jonathan Jones, Heidi Kenyon, Josephine Starrs and Leon Cmielewski, Pamela Kouwenhoven, Kay Lawrence, Fiona McGregor, Tom Nicholson and Ellen Trevorrow.

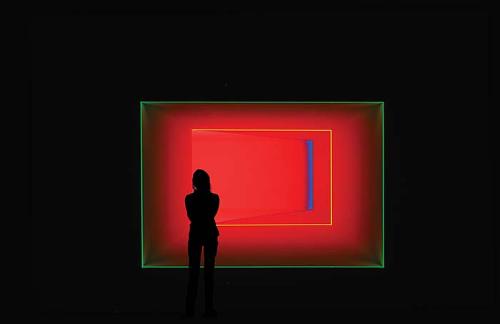

Among the best works were Kenyon’s constructed boxed installations of the literal fluid – Adelaide tap water in the country, Murray River water in the city – linked to very ordinary glass vessels and taps but also through the use of light and darkness, communicating the mystery, the living presence of water. This is what Tom Trevorrow, late husband of weaver Ellen Trevorrow whose Seven Sister baskets featured in a wall installation, also conveyed in his talk given in 2012, and reprinted in the catalogue, where he says ‘The land and waters is a living body’. Trevorrow’s words ‘a living body’ appear to be literally drawn onto the skin of the earth in Starrs and Cmielewski’s video showing an aerial view of the Coorong.

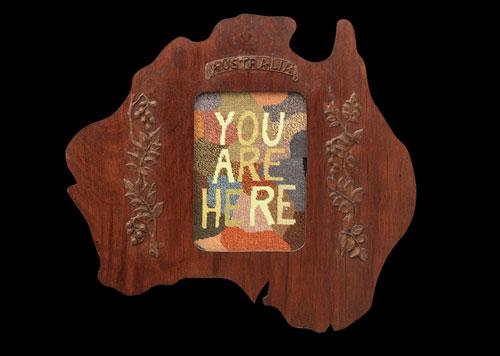

McGregor’s performance, shown in a video, also used the literal stream of Murray water dripping onto her naked body lying on a table of salt. The performance was cut short by hypothermia and we actually see her shudder; this failure to proceed is somehow appropriate. Lawrence’s work also examines failure, in this case the disconnect between terms used in the English language to describe Australian places and the expectations they involve. Lawrence used Jay Arthur’s 2003 book The Default Country: A Lexical Cartography of Twentieth Century Australia to find suitable phrases, and made field trips to paint en plein air along the Murray. These painted phrases in a rubber-resist solution on small sheets of paper with careful stitch-like watercolour river scenes over them, that later came off to reveal the words, was a further act of symbolic erasure.

Overall, significant care and thought made Same River Twice memorable and an important part of a developing new phase of contemporary art where the city and the country work together.