The Perth Institute of Contemporary Art, with its city-centre address and stately Federation clocktower, sustains an institutional aura, inspiring the voluntary adoption of typical gallery protocols like 'don't run’, ‘don’t touch’ and ‘be quiet’. Two recent exhibitions challenged such formalities.

Kinesphere represented a significant opus by Perth-based Erin Coates, bringing together her study of public space, drawing and cinematography skills, with her ‘other’ career as an intrepid rock climber. A series of wall drawings gave diagrammatic form to Coates’ practice of clambering over well-known public artworks in the lonely pre-dawn hours. Coates prefaced her drawings with a definition of thigmotaxis, a term referring to a spatial awareness of the perimeter around one’s body; a kind of sensory extension that manifests in nature as bat sonar, lobster antennae and cat whiskers. In the main gallery, Coates collaborated with engineers and fabricators to produce a monolithic black obelisk, seven metres tall. It housed a micro-cinema showing riveting footage of audacious athletes performing climbs and parkour on familiar urban facades and street furniture, against a vertiginous score by Stuart James.

My own thigmotaxis was tested in Coates’ temporary indoor climbing wall, replete with red crash mats and lined-up tourist shoes. Her video had paraded an elegance and economy of movement. In fact, climbing was tricky and cerebral. The body’s natural momentum does not take over; one must observe, strategise and exert. The video The Last Climber Alive Must Keep Herself Fit and Ready provided an elegiac underscore to the show: a lone female climber (à la Lara Croft) awaits some unspoken threat in a deserted metropolis (actually the Beijing city scale model at China’s Urban Planning Museum). The superimposed climber is glitchy, befitting the sci-fi aesthetic in which we traditionally consume such apocalyptic narratives.

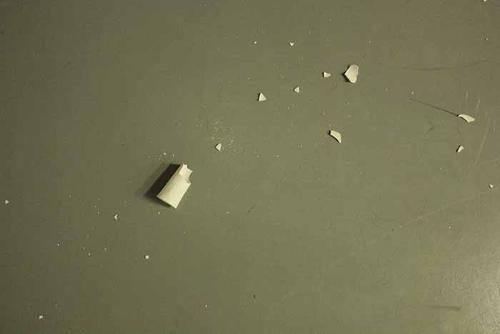

In the west end gallery LA-based George Egerton-Warburton’s installation Administration is Just Oulipan Poetry brought together recent drawing and video around a centerpiece installation created by literally working with the site. Segments of the false wall that formed PICA’s ‘white cube’ space were cut out and rehung from the roof, as a massive, lilting mobile.

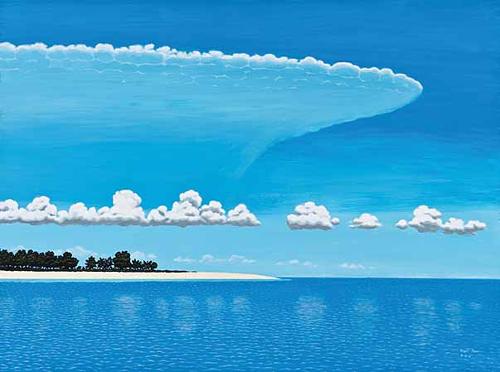

In Egerton-Warburton’s video Boredom is a Desk with Human Legs in a Fish Spa, a strapping male actor manically paces a rural property, reciting eight hectic scripts composed by the artist. His orations each have their own coloured filter, rendering the landscape Gothic, then Arcadian, then picturesque. In a second video, a laptop perched by the seashore like Botticelli’s Venus, played footage of a U-Bank home refinancing ad, its clumsy script looping repetitiously. Both films project scrambled texts into landscapes that otherwise seem to echo aesthetic convention.

Both Coates and Egerton-Warburton are navigators of the parks, streets and galleries we think we know. While public and open, these locations induce learned behaviors that predetermine the ways we move, think and see shared space. These artists introduce the tactile and the disarranged in order to help us re-learn and experience, as if for the first time, what is already around us.