.jpg)

Lights go down, voices too. A low deep music sounds from far off, the beginning of something, then halts. Starts again and stops. Then, close by, a man steps through the knots of people, his bow on the strings of an electric cello high-pitched and disturbing, deep-pitched and thoughtful, rising, stretching out, cutting off discordantly. Again, the low deep melodic call from elsewhere. He arrives, in the dim light coming face to face with himself, video-recorded, playing out there.

There is like no landscape you have ever seen. Hundreds of low white mounds, like proving dough, rise through the red plain. The musician sits in their midst, bent to his acoustic cello. A ring of fire slowly burns its way around him. Beneath the melody lines, two resonant notes sound over and over, a persistent reminder. Of what?

The beauty of the image, with its aura of ancient Greek tragedy, is overturned by the title of the work, Tailings Dam. This visually stunning landscape is the result of human intervention, the crust of an evaporated, once toxic lake. Here is an image of the Fall, the bitter ending of desire. This collaborative work – video and live performance by Pip McManus and Nic Hempel – was shown on opening night of the exhibition Groundrush, the work of six artists who took part in a residency at the Groundrush goldmine in the Northern Territory’s Tanami Desert in 2007.

For Pamela Lofts the show is posthumous. Her death in 2012, following a long illness, is the reason why the exhibition has not eventuated until now. The residency was her idea, and both her presence and her absence heighten the already rather elegiac mood of the whole. Impossible to know how the show might have taken shape otherwise, although the sense of a lost past was probably always going to be there, especially as the Groundrush mine is no longer in production.

A crew of contractors still fly in, fly out, inhabiting a small part of the mining village as the rest deteriorates under the desert sun. Still they get out in their giant earth-movers and trucks, but in rehabilitation mode – the mine is a shadow of what it once was. And, for all the artists’ antics and hilarity – revealed in the photographic documentation that forms part of the show – it’s this lost past that has left its ghostly imprint on their work.

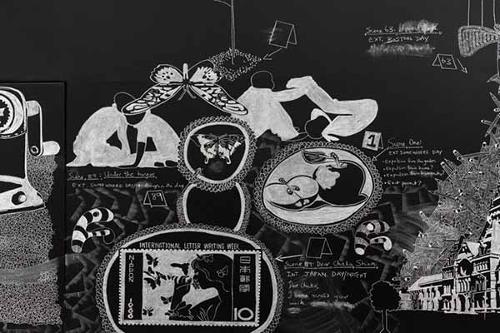

Kim Mahood uses the location’s natural ochres to paint the expanse of its horizons, and then delves deeper to transcribe its “underlying logic” – the parallel contour lines that emerge, whether in mining or rehabilitation works, that are so reminiscent of the contour patterning seen in Aboriginal painting (the mine is on Aboriginal land).Rachel Bowak renders to actual scale the giant tools from the site’s mechanics workshop as line drawings in stainless steel wire. Stripped of their function, they hang from the ceiling and are lit so that they are doubled by their shadows – Bowak’s process is a phantom of the process they (standing in for the rest) have enacted upon the land.

Andrew Moynihan hovered around the semi-abandoned mining village, his eye eventually drawn to the light falling through the tiny perforations in the deteriorating foil on the donga windows, intended to keep out the sun. He videos and photographs the constellations of light dancing across the bare mattresses, traces of the miners’ longing for life beyond their present rule-bound work-sleep routine. Then in a reversal of this metaphorical camera obscura he puts his eye to the pinholes, to discover the world outside: a wheeling bird, clouds, spinifex blowing in the wind, a dingo who seems to return his gaze.

Lofts led Hempel – a musician but also a physical performer in the Butoh and Body Weather traditions – to the “scats”, great sterile piles of grey processed ore. Without saying much, she gave him props – bandages, some small golden balls, a hi-vis vest, a miner’s hat – and photographed what he did with them. The work, Dancing on the Scats, was unfinished at the time of her death; Mahood brought it to completion as a video compilation of the still images. Hempel, his bare torso wrapped with the bandages, packs an erotic charge into his performance of the lust for gold, and then ranges through the hubris and the violence of mining and miners, their sometime absurdity, sometime vulnerability.

The whole gallery is imbued by Hempel’s unsettling, often sorrowful music featuring in two further collaborative works with McManus. And on the floor long shadows – in black rubber, by Bowak – as if left behind by the person who once cast them. Traces of a mourned past leading to, who knows, what future.

Note: Groundrush is touring to the Canberra Contemporary Art Space in 2015.