It took a lot of brooding and ruminating. A lot of pondering and deliberating. Once the twin weights of responsibility and trepidation were able to be managed, there was an intense period of planning and beavering away in order to get a folio together. And even after that it took a course in picking-up-confidence at Brisbane's Relaxation Centre before Gordon Bennett mustered enough courage to put down his tools at Telstra and walk through the doors of an art college.

Contemporary Australia should be very grateful to that Relaxation Centre course – it provided the leverage to launch a career that has changed the way we think about Australian history, about ourselves as Australians, and about what we might be. And even after all these efforts to build up a head of steam, Gordon’s initial application into an art college was knocked back by QUT. History now describes how he was admitted into Queensland College of Art where he wasted no time embarking on a sustained and intense process of thinking and making that continues to resonate, to challenge and to question.

Gordon was born in 1955 in Monto, the son of Don and Grace. He earned a trade certificate in Fitting and Turning and later worked as a linesman for Telstra. From his father Gordon inherited an Anglo-Celtic Australian heritage and from Grace an Australian Indigenous heritage. When he married Leanne in 1977 he settled in the suburbs of Brisbane. Before that he’d lived around rural Victoria and Queensland, where he’d become familiar with the easy-going racism that slides in and out of everyday conversations and attitudes right across this country. He’d listened to enough of it during smoko sessions and the like to recognise the often languid delivery of racial denigration and vilification. The Indigenous aspect of his own heritage had only been revealed to him in his early teens, and his growing awareness of how this part of his identity was recognised by others was delivered in a steady daily dose of sickening jabs: the abc of abo, boong, coon, darkie that flit in and out of run-of-the-mill pleasantries.

By the time he began his art training in 1986 he was 30. He walked tall and carried himself like he knew how to make things work. He was reserved and dignified and spent little time either suffering fools or wasting time. He didn’t waste words either. If there was, from time to time, an edge of bitterness against those edges of Australian society that exhibit intolerance, then he was quick to re-wire the electricity of such emotions into the images and words and performances that have allowed each of us to see such things more clearly. And if Gordon’s images ever appear uncompromising, it’s worth bearing in mind that he was always toughest on himself. He never permitted himself to be identified as an “Indigenous artist”. In a letter written to the Haitian-Puerto Rican American artist Jean-Michel Basquiat after his death, he describes Australia’s official acclamation of him as “an urban Aboriginal artist” as a title that “I do not wear (it) well”. He faced his own inner divisions with an uncompromising focus that incapacitated the graceless stupidity of easy identifications or identity. And he carried it forward in real terms, refusing to have his work purchased as part of the Indigenous collections of state galleries or private collections.

So much of his art was driven by this – a kind of scalpel-sharp commitment to the savage compromises necessary to cut beneath the thin skin of facile identity. In this sense his work effectively ducks and weaves, parries and feints at any fixities of characterisation. As part of this resistance, he produced a roll-call of what (he) was not: words that tumble down the faces of his paintings and drawings in a welter and cadence that reveal the inter-connection and inter-dependency between identity and racism: words such as peasant, colonist, squatter, migrant, alien, ethnic, native, aborigine, autochthon, indigene that were both the subject of the works as well as the formal components within the work. For in Gordon’s work words are images. He used them in full recognition of their power as icons or weapons or signposts. But he also used them to reveal their failure to accommodate the complexities of being.

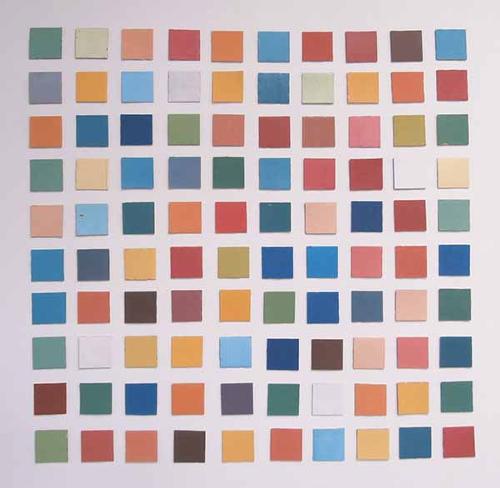

Another of Gordon’s strategies of eliding fixed identity entailed adopting and adapting from a roll-call of artists against which he implicitly continued his reassertion of “what he was not”: from the definitive image-banks of Mondrian, Pollock, Preston, Tjakamarra, Kngwarreye, Tillers, Baselitz, Basquiat, Lichtenstein, Guston and others, Gordon begged and borrowed, bartered and bastardised elements that he re-constituted in compositions where the contradictions and alienation of identity were reinstated with ironical inventiveness. He also took and transformed images from Indigenous artists to reinstate “what he was not”– Mimi-like figures and Wandjina-like heads and spirit forms that he overlaid and crippled and grafted to the body-parts of the History of Art (western style). And, in this sense, Gordon offered us that imagery of a divided self that all Australians – both non-indigenous as well as Indigenous – are capable of recognising. And any beauty in those divided, often tortured, mutilated representations of self lies in his unwavering commitment to facing the complexities and contradictions of the matter.

During the three years Gordon spent at art college, Australia was engaged in the run-up to the Bicentennial celebrations – a time when the voices of Indigenous Australians were delivered with an articulacy, clarity and coherence that could not be muffled by the official celebrations. At the same time the self-described local ‘art world’ was embroiled in discussions that were tepid compared to the realpolitik of the streets; nevertheless the potential offered by the appropriations of postmodernism offered more than a stylistic affectation to Gordon, even though he characteristically refused to be collectively identified as an “appropriation artist”.

The Coming Of The Light (1987) was painted during his second year at College. From the vantage-point of the present it’s an image brimming with clues about the issues the artist would continue to grapple with for the next 27 years – ideas about how the influences of language, religion and history structure our understanding of race and identity. The gridded skyscrapers of the metropolis deliver a conveyor-belt of alphabet-blocks that capture and constrict the identities of those who peep out with Guston-like gazes. Above them hover the twin fists of enlightenment and reason: one grips a torch that illuminates the painterly McCahon-like smears of the wall beyond; the other grasps the dog-collar/noose that wrenches the black jack-in-the-box out of the ‘A’ alphabet box. So much of it is already there – the homage to American painting; the homage to the visionary McCahon; the critique of modernism; the constricting power of language; painterliness next to hard-edge, and, above all, the implication that we’re all damned – black and white – by this mess we’re in. And there’s a mirror – one into which the black Jack looks back at his own reflection just at the point at which he gets hanged.

But by the next year, when Outsider (1988) appeared in the painting studios, it was immediately apparent that Gordon’s use of appropriation from the canon of western painting was both homage and critique; it had nothing of the cooler stylistic quotation evident in so much of what might have appeared suspiciously like art at the time. And while Australia was waking up to its black history, Brisbane was also waking up to cultures beyond the mission brown of its suburban fence-lines; in 1988 World Expo was hosted on the banks of the Brisbane River just down from the Queensland Art Gallery. The cultural, historical and social ferment of the time was harnessed productively by a number of artists, and although Gordon moved in and between artistic groups and individuals, his was a voice with a clear singularity of purpose; he was astute in recognising that the subject matter for his own practice came ‘out of small town and suburban Australia’ rather than from the styles promoted from inside the ‘art world’.

Gordon’s art was as firmly rooted in personal experiences of family as it was in the contemporary issues of the day. By 1989 he’d produced Triptych: Requiem, Of grandeur, Empire for the Art Gallery of New South Wales’ Perspecta, a national survey of contemporary art. We shared the same room for that exhibition, and although Gordon’s painting was modest in scale, its resonance reverberated with power and clarity; in a single work he’d shackled the entire history of representational one-point perspective to a visceral interpretation of the Australian landscape infused by Christian iconography and its costs. In the central panel a painted image of Gordon’s mother Grace seems engaged in the act of cleaning the feet of an absent Jesus – to the right is the photographic image of his mother “in training” for a career in domestic help at Singleton after being raised as an orphan on Cherbourg Aboriginal Mission. Even by the time of Gordon’s birth, Grace was required by the government to carry a certificate verifying her official exemption from the Mission with her as proof of her right to identity.

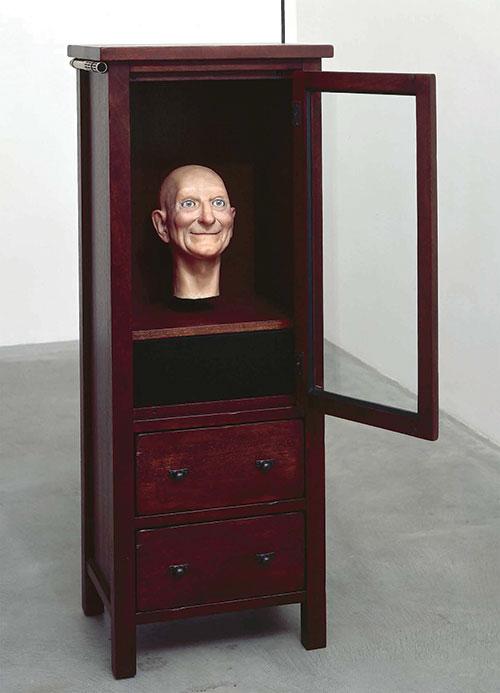

By the mid 1990s, Gordon had folded part of himself into the creation of John Citizen, the identity-neutral artist-for-everyman. Like Gordon, John Citizen also borrowed and begged, pilfered and plundered from the works of other artists, including those of Gordon Bennett, in a role that both parodied and performed the becoming of the artist’s identity-as-an-artist. But this too was to be killed and buried. In his hauntingly titled 1996 Performance with object for the expiation of guilt (Violence and grief remix), shadow-forms reflect Bennett’s own lean, restless figure as he prowls relentlessly around a coffin-like box he regularly takes aim at with a whip. The performance is overlaid by images taken from Bennett’s own paintings as well as historical footage of Indigenous people. It offers a sequence of unforgettable imagery that lashes back at the ‘silence, self-loathing and denial of heritage’ that formed both the burden and the fulcrum for the artist’s work.

Throughout his life Gordon’s work continued to methodically vivisect and reconstitute who he might be. Images were always contingent, overlaid, transparently reconstructed and bore all the traces of their former roles like a series of battered, war-weary survivors. His last series of work, the Abstraction (Citizen) Drawings, continued his riff on the mercurial obscuring and revealing of mutating identities in which outlines of celebrities and politicians hover like a series of linear nooses in front of the often anguished figures of the iconic “Indigenous” figures behind them. Yet the influences of each of these figurative references run both ways like an AC/DC current, each charging the force and potential of the other, as if the perpetrators and the victims are interdependent on the charge of energy between them. And behind all this charge runs a series of finger-smudged hatchings – hand-made grids that fumble and smear in their poignant attempt to hatch out some semblance of order. And below, the words again, that run across each of the paintings like a low horizon: slummer; peasant; fringe dweller.

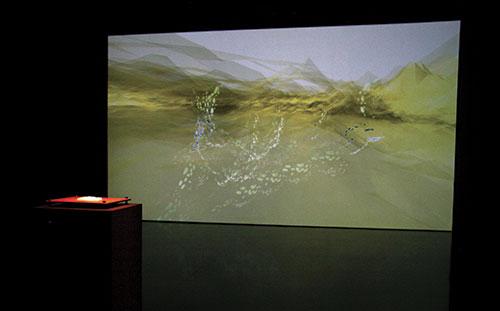

It could be that there’s a great skill attached to inhabiting these edges – of slumming like a peasant or a fringe dweller. There’s no question that Gordon had an impressive share of the international art world’s attention – his work featured in the 8th Berlin Biennale; new international audiences applauded his work in Documenta13 in Kassel, Germany in 2012 and the spotlight of artworld attention was constantly seeking him out. But throughout his life he practised a skill of skulking off to just one side of that spotlight, slinking into the darkness in order to better see things from another angle. Gordon once described John Citizen in this way: “As far as pinning down who John Citizen actually is, I’m not interested in doing that. His identity must remain fluid. He is in a sense all things to all people. He can be anything the viewer wants him to be: white, black or any shade in between, as is true of Australian citizens in general in our multicultural country.”

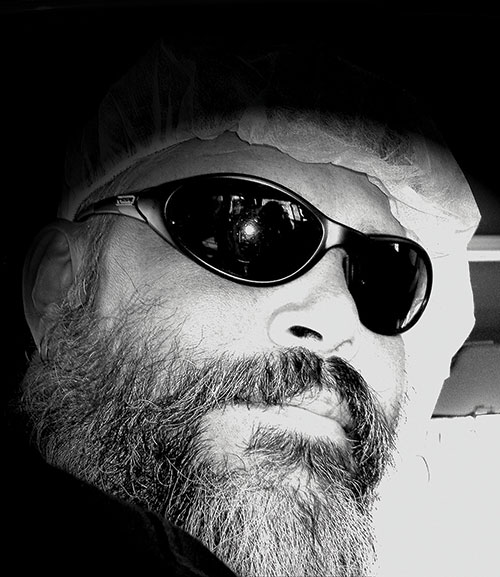

Gordon went to pains to refuse to talk about his work publicly. That choreographed absence somehow had the effect of making him more present in his work. It was as if he was there in the background, observing your observing, watching your responses as a viewer, making you more aware of the implications of your own role.

This practised absence, among other things, makes it very difficult to imagine that Gordon’s no longer there, brooding on the edges, worrying over the details and data, restlessly pacing the perimeters of what’s acceptable and what’s hidden. Each of us owes him a great deal. He worked long and hard to wake us in fright to what we’d hoped we weren’t really seeing. There’s a lot written about him, and there will be a lot more. But to describe him as an ‘artistic genius” is the kind of throw-away identity tag that would have made him gag. Rather, he was an artist with the intelligence to face his history and his present; who retained a single minded dedication to articulating what he saw with increasing clarity; who could face up to a range of demons and dare them into representation; and who offered his vision of Australia as an imperfect place with a rare honesty. And that’s pretty well as good as it gets.